Testing for Resistance to Smallpox in

People Who Have Been Inoculated with Cow-pox

After the many fruitless attempts to give the smallpox to those who had

the cow-pox, it did not appear necessary, nor was it convenient to me,

to inoculate the whole of those who had been the subjects of these late

trials; yet I thought it right to see the effects of variolous matter on

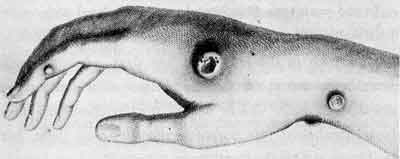

some of them, particularly William Summers, the first of these patients

who had been infected with matter taken from the cow. He was, therefore,

inoculated with variolous matter from a fresh pustule; but, as in the preceding

cases, the system did not feel the effects of it in the smallest degree.

I had an opportunity also of having this boy and William Pead inoculated

by my nephew, Mr. Henry Jenner, whose report to me is as follows:

"I have inoculated Pead and Barge, two of the boys whom you

lately infected with the cow-pox. On the second day the incisions

were inflamed and there was a pale inflammatory stain around them.

On the third day these appearances were still increasing and their arms

itched considerably. On the fourth day the inflammation was evidently

sudsiding, and on the sixth day it was scarcely perceptible. No symptom

of indisposition followed.

"To convince myself that the variolous matter made use of was in

a perfect state I at the same time inoculated a patient with some of it

who never had gone through the cow-pox, and it produced the smallpox in

the usual regular manner."

These experiments afforded me much satisfaction; they proved that the matter,

in passing from one human subject to another, through five gradations,

lost none of its original properties, J. Barge being the fifth who received

the infection successively from William Summers, the boy to whom it was

communicated from the cow.

General Observations

I shall now conclude this inquiry with some general observations on the

subject, and on some others which are interwoven with it.

Although I presume it may be unnecessary to produce further testimony

in support of my assertion "that the cow-pox protects the human constitution

from the infection of the smallpox," yet it affords me considerable satisfaction

to say that Lord Somerville, the President of the Board of Agriculture,

to whom this paper was shewn by Sir Joseph Banks, has found upon inquiry

that the statements were confirmed by the concurring testimony of Mr. Dolland,

a surgeon, who resides in a dairy country remote from this, in which these

observations were made. With respect to the opinion adduced "that

the source of the infection is a peculiar morbid matter arising in the

horse," although I have not been able to prove it from actual experiments

conducted immediately under my own eye, yet the evidence I have adduced

appears sufficient to establish it.

They who are not in the habit of conducting experiments may not be aware

of the coincidence of circumstances necessary for their being managed so

as to prove perfectly decisive; nor how often men engaged in professional

pursuits are liable to interruptions which disappoint them almost at the

instant of their being accomplished: however, I feel no room for

hesitation respecting the common origin of the disease, being well convinced

that it never appears among the cows (except it can be traced to a cow

introduced among the general herd which has been previously infected, or

to an infected servant) unless they have been milked by some one who, at

the same time, has the care of a horse affected with diseased heels....

-

May it not ... be reasonably conjectured that the source of the smallpox

is morbid matter of a peculiar kind, generated by a disease in the horse,

and that accidental circumstances may have again and again arisen, still

working new changes upon it until it has acquired the contagious and malignant

form under which we now commonly see it making its devastations amongst

us?

-

And, from a consideration of the change which the infectious matter undergoes

from producing a disease on the cow, may we not conceive that many contagious

diseases, now prevalent among us, may owe their present appearance not

to a simple, but to a compound, origin?

-

For example, is it difficult to imagine that the measles, the scarlet fever,

and the ulcerous sore throat with a spotted skin have all sprung from the

same source, assuming some variety in their forms according to the nature

of their new combinations?

The same question will apply respecting the origin of many other contagious

diseases which bear a strong analogy to each other.

Natural Varieties of Smallpox

There are certainly more forms than one, without considering the common

variation between the confluent and distinct, in which the smallpox appears

in what is called the natural way. About seven years ago a species

of smallpox spread through many of the towns and villages of this part

of Gloucestershire: it was of so mild a nature that a fatal instance

was scarcely ever heard of, and consequently so little dreaded by the lower

orders of the community that they scrupled not to hold the same intercourse

with each other as if no infectious disease had been present among them.

I never saw nor heard of an instance of its being confluent. The

most accurate manner, perhaps, in which I can convey an idea of it is by

saying that had fifty individuals been taken promiscuously and infected

by exposure to this contagion, they would have had as mild and light a

disease as if they had been inoculated with variolous matter in the usual

way. The harmless manner in which it shewed itself could not arise

from any peculiarity either in the season or the weather, for I watched

its progress upwards of a year without perceiving any variation in its

general appearance. I consider it then as a variety of the

smallpox.

Proper and Improper Inoculation Methods

...A medical gentleman (now no more), who for many years inoculated in

this neighbourhood, frequently preserved the variolous matter intended

for his use on a piece of lint or cotton, which, in its fluid state, was

put into a vial, corked, and conveyed into a warm pocket; a situation certainly

favourable for speedily producing putrefaction in it. In this state

(not unfrequently after it had been taken several days from the pustules)

it was inserted into the arms of his patients, and brought on inflammation

of the incised parts, swellings of the axillary glands, fever, and sometimes

eruptions.

But what was this disease?

Certainly not the smallpox; for the matter having from putrefaction

lost or suffered a derangement in its specific properties, was no longer

capable of producing that malady, those who had been inoculated in this

manner being as much subject to the contagion of the smallpox as if they

had never been under the influence of this artificial disease; and many,

unfortunately, fell victims to it, who thought themselves in perfect security....

Whether it be yet ascertained by experiment that the quantity of variolous

matter inserted into the skin makes any difference with respect to the

subsequent mildness or violence of the disease, I know not; but I have

the strongest reason for supposing that if either the punctures or incisions

be made so deep as to go through it and wound the adipose membrane, that

the risk of bringing on a violent disease is greatly increased.

I have known an inoculator whose practice was "to cut deep

enough (to use his own expression) to see a bit of fat," and there to lodge

the matter. The great number of bad cases, independent of inflammations

and abscesses on the arms, and the fatality which attended this practice,

was almost inconceivable; and I cannot account for it on any other principle

than that of the matter being placed in this situation instead of the skin.

It was the practice of another, whom I well remember, to pinch up a

small portion of the skin on the arms of his patients and to pass through

it a needle, with a thread attached to it previously dipped in variolous

matter. The thread was lodged in the perforated part, and consequently

left in contact with the cellular membrane. This practice was attended

with the same ill success as the former....

A very respectable friend of mine, Dr. Hardwicke, of Sodbury in this county,

inoculated great numbers of patients ... and with such success that a fatal

instance [rarely] occurred.... It was the doctor's practice to make

as slight an incision as possible upon the skin, and there to lodge a thread

saturated with the variolous matter. When his patients became indisposed,

agreeably to the custom then prevailing, they were directed to go to bed

and were kept moderately warm.

Is it not probable then that the success of the modern practice may

depend more upon the method of invariably depositing the virus in or upon

the skin, than on the subsequent treatment of the disease?...

I cannot account for the uninterrupted success, or nearly so, of one

practitioner, and the wretched state of the patients under the care of

another, where, in both instances, the general treatment did not differ

essentially, without conceiving it to arise from the different modes of

inserting the matter for the purpose of producing the disease....

Advantages of Cow-pox over Smallpox Inoculation

Unlike Smallpox, Cow-pox is Not Fatal

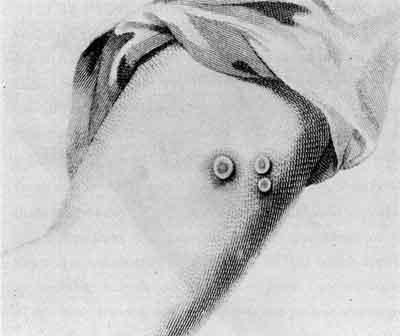

Should it be asked whether this investigation is a matter of mere curiosity,

or whether it tends to any beneficial purpose, I should answer that, notwithstanding

the happy effects of inoculation, with all the improvements which the practice

has received since its first introduction into this country, it not very

unfrequently produces deformity of the skin, and sometimes, under the best

management, proves fatal.

These circumstances must naturally create in every instance some degree

of painful solicitude for its consequences. But as I have never

known fatal effects arise from the cow-pox, even when impressed in

the most unfavourable manner, producing extensive inflammations and suppurations

on the hands; and as it clearly appears that this disease leaves the

constitution in a state of perfect security from the infection of the smallpox,

may we not infer that a mode of inoculation may be introduced preferable

to that at present adopted, especially among those families which,

from previous circumstances, we may judge to be predisposed to have the

disease unfavourably?

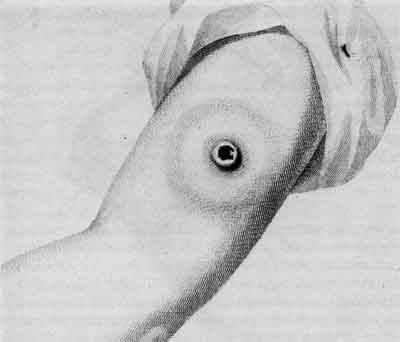

It is an excess in the number of pustules which we chiefly dread in

the smallpox; but in the cow-pox no pustules appear, nor does it seem possible

for the contagious matter to produce the disease from effluvia, or by any

other means than contact, and that probably not simply between the virus

and the cuticle; so that a single individual in a family might at any time

receive it without the risk of infecting the rest or of spreading a distemper

that fills a country with terror.

Cow-pox Is Not Transmitted by Air

Several instances have come under my observation which justify the assertion

that the disease cannot be propagated by effluvia. The first boy

whom I inoculated with the matter of cow-pox slept in a bed, while the

experiment was going forward, with two children who never had gone through

either that disease or the smallpox, without infecting either of them.

A young woman who had the cow-pox to a great extent, several sores which

maturated having appeared on the hands and wrists, slept in the same bed

with a fellow-dairymaid who never had been infected with either the cow-pox

or the smallpox, but no indisposition followed.

Another instance has occurred of a young woman on whose hands were several

large suppurations from the cow-pox, who was at the same time a daily nurse

to an infant, but the complaint was not communicated to the child.

Cow-pox Produces Few Complications to Existing Conditions

In some other points of view the inoculation of this disease appears preferable

to the variolous inoculation.

In constitutions predisposed to scrophula [swellings

of the neck often associated with tuberculosis], how frequently

we see the inoculated smallpox rouse into activity that distressful malady!

This circumstance does not seem to depend on the manner in which the distemper

has shewn itself, for it has as frequently happened among those who have

had it mildly as when it has appeared in the contrary way.

There are many who, from some peculiarity in the habit, resist the common

effects of variolous matter inserted into the skin, and who are in consequence

haunted through life with the distressing idea of being insecure from subsequent

infection. A ready mode of dissipating anxiety originating from such

a cause must now appear obvious. And, as we have seen that the constitution

may at any time be made to feel the febrile attack of cow-pox, might it

not, in many chronic diseases, be introduced into the system, with the

probability of affording relief, upon well-known physiological principles?...

____________

Thus far have I proceeded in an inquiry founded, as it must appear,

on the basis of experiment; in which, however, conjecture has been occasionally

admitted in order to present to persons well situated for such discussions,

objects for a more minute investigation. In the mean time I shall

myself continue to prosecute this inquiry, encouraged by the hope of its

becoming essentially beneficial to mankind. |