HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

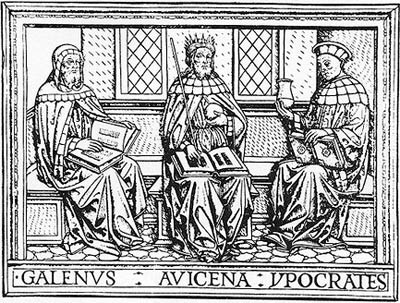

With us there was a Doctour of Phisyk

In al this world ne was there noon him lyk To speke of phisik and of surgerye... Wel knew he the olde Esculapius (Aesculapius) And Deyscorides (Diascorides) and eek Rufus (Rufus of Ephesus) Olde Ypocras (Hippocrates), Haly (Ali ben-Abbas) and Galeyn (Galen), Serapion (Serapion of Alexandria [1st c CE] or Serapion the Younger [12th c], Razi (Rhazes) and Avycen (Avicenna)... --from the Prologue to The Canterbury Tales (c. 1390) |

_________________ |

The good physician should:

|

Handing-on the Art of Healing |

|||

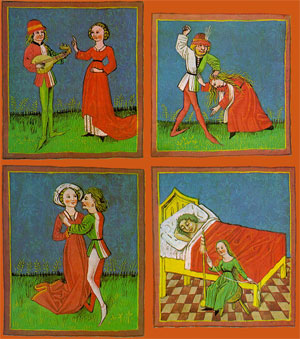

Europeans had limited access to the works of Hippocrates and Galen before 1000 CE. Healing was less an art than a practiced craft. Illness itself aroused ambivalent feelings. If a disease was the result of divine action (possibly to test or punish the victim), it might be sinful to interfere with its course except through prayer, repentence and hope for a miracle. On the other hand, those who ministered to the needs of the sick were considered agents of charity. Many were members of the clergy. Surely it was good to do whatever was necessary to restore the well-being of the temple of the soul. Still, it was best to avoid getting sick in the first place! One's chances for preserving and maintaining good health could be improved by keeping the body's four humors in balance through routine bleeding or cupping:

A patient is bled to insure humors are kept in balance. Another way to prevent illness was to keep the body free of harmful toxins:

A clyster (enema) was often used to purge a patient of the toxins in bodily waste. | |||

| Monastery schools (~5th c)

Goals:

|

| ||

Monks prepare herbal medicines. |

|||

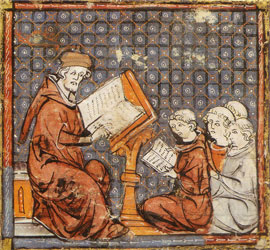

Cathedral schools (8th c)

|

|

||

Universities (12th c)

|

Although its origins are hazy, the first formal European medical school was founded in Salerno, Italy around the 9-10th century CE. Its early teachers included Greeks, Romans, Jews and Muslims. Women were admitted as pupils. The curriculum included anatomy, dissection, practical medicine and professional behavior. |

||

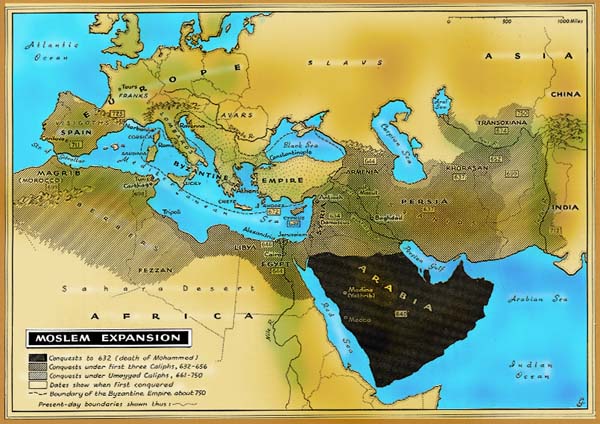

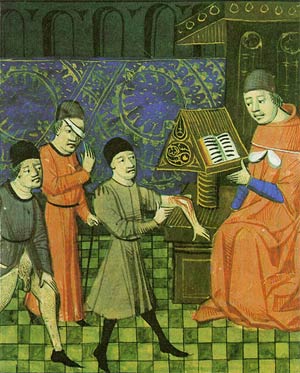

Medical school at Jundishapur

(~ 6th c)

Thanks to the the survival of Greek learning in the Middle East, institutions for formal medical education were organized there far earlier than in the West. An academy modeled on the famed Museum in Alexandria was established in Jundishapur in 560 CE by the enlightened Persian leader, Khosru I. As a major repository for ancient Greek texts, Jundishapur attracted many teachers and students interested in the practice of medicine. Teachers provided their pupils with certificates to show they had studied and mastered the medical arts. After Arabs conquered Persia in 638, Jundishapur became a center for translating Greek, Syriac and Indian texts into Arabic and Persian. In 931, the Caliph of Baghdad introduced examinations for medical students to demonstrate their skill and proficiency. |

|

Spread of Islam from the time of the death of Mohammed (632) to 750 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Training in Medical Theory |

||

The fifty-year period between 1285-1335 was a transitional period in which medical practice in Europe took firm shape as a secular occupation. Church officials questioned whether a cleric could continue to serve as a priest after the death of a patient under his care. Regulations were introduced forbidding priests to practice surgery, although they were permitted to treat wounds, sores and fractures. For a time, monks were forbidden to leave their monasteries to study medicine, although this impractical rule was eventually softened. Thanks to Avicenna, the works of Galen were finally being put into a form that could be fruitfully studied. Concordances and summaries appeared as teaching aids. Europeans began to view medicine as more of a science than an art or a craft. Best practice can be derived from first principles rather than trial and error:

Those who read Galen's works carefully discovered occasional conflicts with Aristotle and other authorities. Teachers and students worked to reconcile these differences through academic disputation. |

||

| Melancholic

moody glum Sanguine

|

|

Choleric

irritable hot-tempered Phlegmatic

|

Training in Medical Practice |

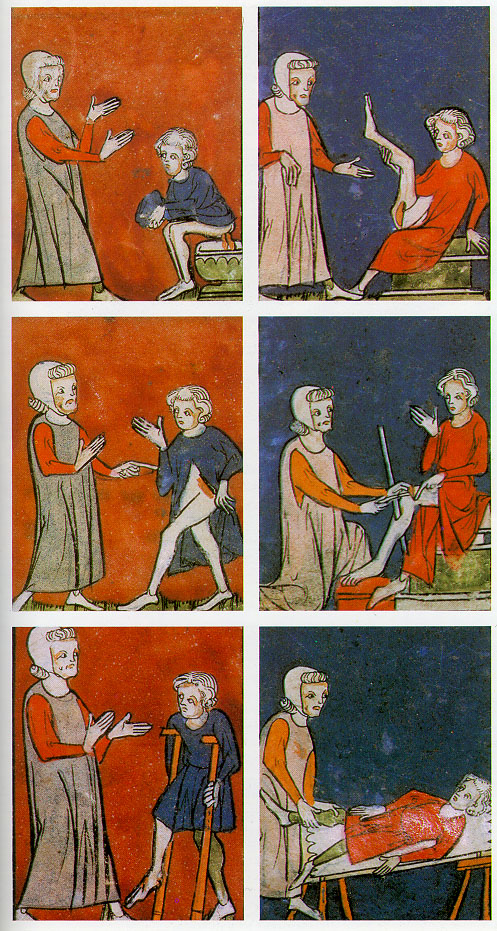

Illustrations from the Livre de Chirurgie (13th c.) show the physician treating patients who are suffering from a variety of complaints. Regardless of the horror presented by the injury (note the stake through the leg, center right) or the repulsiveness of the symptoms (diarrhea, top left), the neatly dressed physician is always calm and reassuring. The illustrations are unaccompanied by captions. They are intended to serve as a guide to the information elsewhere in the text and to be explained by someone knowledgeable. |

The Medical School at Salerno |

Salerno was a major center for translating ancient manuscripts from Arabic into Latin

|

1140 |

|

1200 |

|

1230 |

|

|

[Physicians] boast that they understand an illness when they don't. They drag illnesses out so that they can get more money from the sick. They prescribe syrups and electuaries and other things for the sick because they share in the profits that the apothecaries make on what they sell to their patients. Every day we see that when the physician's cure goes wrong, he blames it on the patient, saying that he hasn't followed the right diet or didn't tell the truth about his illness. It is they who should be blamed for the mistakes they make, yet they blame the patient, who doesn't deserve it. Physicians who first of all understand the illness, they ... can treat it: but every day we see physicians treating their patients haphazardly because they don't understand the illness. --Ramon Llull (1272) |

| Sicily:

No one claiming the title of medicus is to practice unless he should come to the king with letters from the masters of Salerno testifying to his trustworthiness and sufficient knowledge.... Pope Gregory IX:

Salerno's requirements for independent practice:

|

Who practiced the healing arts? |

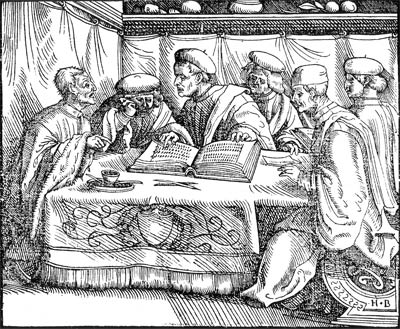

Physicians

Physicians consult the textbook. |

Surgeons

A surgeon sees patients in his clinic. |

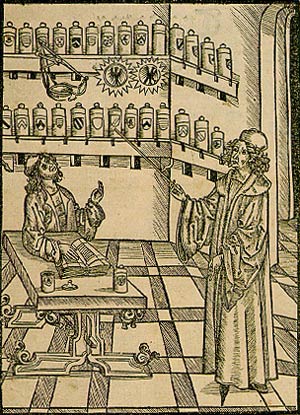

Apothecaries

[supplemented income as grocer, chandler, or other occupation based on selling products used in apothecary business]

A physician selects a remedy at the apothecary's shop. |

Barbers

[supplemented income with mule-trading, iron-selling, cloth dyeing, offering surgical treatments for which they were nominally unqualified]

The barber pulls a tooth with the aid of his lovely assistant. |

How were the healing arts practiced? |

1. Consult one of a new genre of literature -- the health care guide:

|

2. Deduce a diagnosis

Guide for analyzing urine. |

3. Provide patient with a prognosis

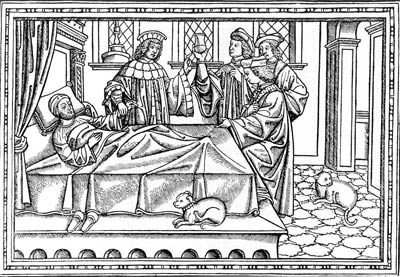

Physicians consider the diagnosis and contemplate a prognosis. |

4. Prescribe therapeutic procedures

|

Where were the healing arts practiced? |

Home

Midwives deliver a baby while astrologers cast its horoscope. |

Apothecary shop

|

Urban hospitals

|

Lazarettos and pest-houses

|

Valetudinaria

|

|

| Go to: |

|

|