HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

October 1980 -- May 1981

|

June 1981

|

|

June 5, 1981 / Vol. 30/ No. 21/ pp. 250-252 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention A Cluster of Kaposi's Sarcoma and Pneumocystis carinii Pneumonia among Homosexual Male Residents of Los Angeles and Orange Counties, California In the period October 1980-May 1981, 5 young men, all active homosexuals, were treated for biopsy-confirmed Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia at 3 different hospitals in Los Angeles, California. Two of the patients died. All 5 patients had laboratory-confirmed previous or current cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection and candidal mucosal infection. Case reports of these patients follow. Patient 1: A previously healthy 33-year-old man developed P. carinii pneumonia and oral mucosal candidiasis in March 1981 after a 2-month history of fever associated with elevated liver enzymes, leukopenia, and CMV viruria.... He died May 3, and postmortem examination showed residual P. carinii and CMV pneumonia, but no evidence of neoplasia. Patient 2: A previously healthy 30-year-old man developed p. carinii pneumonia in April 1981 after a 5-month history of fever each day and of elevated liver-function tests, CMV viruria,.... His pneumonia responded to a course of intravenous TMP/.SMX, but, as of the latest reports, he continues to have a fever each day. Patient 3: A 30-year-old man was well until January 1981 when he developed esophageal and oral candidiasis that responded to Amphotericin B treatment. He was hospitalized in February 1981 for P. carinii pneumonia.... Patient 4: A 29-year-old man developed P. carinii pneumonia in February 1981.... He did not improve ... and died in March.... Patient 5: A previously healthy 36-year-old man with clinically diagnosed CMV infection in September 1980 was seen in April 1981 because of a 4-month history of fever, dyspnea, and cough. On admission he was found to have P. carinii pneumonia, oral candidiasis, and CMV retinitis.... The diagnosis of Pneumocystis pneumonia was confirmed for all 5 patients antemortem by closed or open lung biopsy. The patients did not know each other and had no known common contacts or knowledge of sexual partners who had had similar illnesses. The 5 reported having frequent homosexual contacts with various partners. All 5 reported using inhalant drugs, and 1 reported parenteral [injected] drug abuse.... Reported by MS Gottlieb, MD, et al., Div of Clinical Immunology-Allergy; Dept of Medicine, UCLA School of Medicine; I Pozalski, MD, Cedars-Mt. Sinai Hospital, Los Angeles; Field services Div, Epidemiology Program Office, CDC. Editorial Note: Pneumocystis pneumonia in the United States is almost exclusively limited to severely immunosuppressed patients.... The occurrence of pneumocystosis in these 5 previously healthy individuals without a clinically apparent underlying immunodeficiency is unusual. The fact that these patients were all homosexuals suggests an association between some aspect of a homosexual lifestyle or disease acquired through sexual contact and Pneumocystis pneumonia in this population.... All the above observations suggest the possibility of a cellular-immune dysfunction related to a common exposure that predisposes individuals to opportunistic infections such as pneumocystosis and candidiasis. Although the role of CMV infection in the pathogenesis of pneumocystosis remains unknown, the possibility of P. carinii infection must be carefully considered in a differential diagnosis for previously healthy homosexual males with dyspnea and pneumonia. |

July 1981

|

Kaposi's sarcoma |

CDC had just completed a cooperative study with a number of gay community

health clinics--a multiyear, multisite study of hepatitis B:

|

|

mid-1981

|

July 1981

|

August 1981

|

June 1982

|

July 1982

|

September 1982

|

December 1982

|

March 1983

|

| Meanwhile..... |

|

1960s

1970

1976

1979

1982

1983

1984

|

|

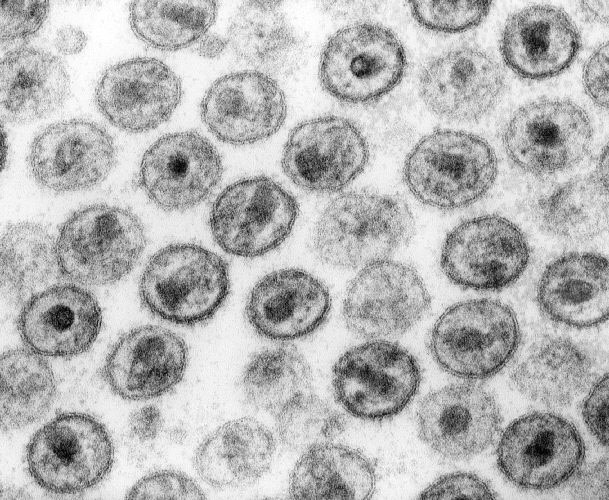

HIV particles |

__________ Should HIV testing be compulsory??? Should HIV-positive individuals be required to register with local health officials??? Should the names of HIV-positive individuals be made

public???

|

|

In 1999, two epidemiologists debated the question: "Is confidential named HIV reporting a proper approach to fighting the epidemic in California?" |

|

YES HIV CAN BE PREVENTED IF THE INFECTED PERSON'S IDENTITY IS KNOWN by Ralph R. Frerichs, D.V.M., Dr.P.H. Dr. Frerichs is professor and chair of the Department of Epidemiology at the UCLA School of Public Health. |

NO FEAR IS THE MAIN BARRIER TO TESTING AND CARE by Walton Senterfitt, R.N., M.PH. Dr. Senterfitt is a practicing epidemiologist and health planner, longtime AIDS activist and Person Living With AIDS. |

What's in a name? A lot, when it comes to an unrecognized infections disease that spreads by intimate person-to-person contact. While not difficult to prevent if detected, the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) differs from other communicable diseases in two respects. First, the virus is closely identified with gays, and has become entwined in gay political concerns such as open identification, discrimination and social acceptance. Second, those who harbor the virus have become vocal and organized. They serve as a strong lobbying force against legislative actions that limit their personal freedoms, which sometimes involve viral transmission. HIV remains a cunning foe, difficult to treat and rid from the body, but not hard to prevent if the identity of the HIV-infected person is known. In general, health departments in the majority of states that now have named HIV reporting (31 at last count, but not California) make good use of the identity of HIV-infected persons. The gathered data are easily checked for duplication in count, thereby improving the quality of the surveillance system. Contact is maintained with persons who are infected and their susceptible spouses or sexual partners. Such susceptible persons can then protect themselves from HIV by avoiding sexual or blood contact, or by reducing their risk with condoms, withdrawal or use of clean needles. For HIV-infected persons, treatment is an expensive long-term undertaking that requires follow-up and support beyond what is offered by busy physicians. Having names helps health departments maintain such contact and encourages public support for the cost of therapy. Finally, in the case of pregnancy, having a name allows medical and public health workers to ensure early treatment, necessary to preserve the life of the newborn child. For these reasons, I strongly support named HIV reporting, along with confidentiality safeguards that are standard when dealing with sexually transmitted diseases. |

One-third of HIV-infected persons in Los Angeles County are not aware of their infection. Of those who do know, at least 25 percent are not receiving care. Named reporting will do almost nothing to help identify and assist these persons, who contribute most heavily to the continued spread of HIV. A small but significant proportion of individuals will decline testing or services if their names are to be confidentially reported to an agency of the state. The actual risk of disclosure by public health staff is infinitesimal, but this is beside the point. Fear, regardless of whether it is founded in reality, is the main barrier to testing and care. Public health must address the continued social stigma underlying these fears. Instead, advocates of named reporting have fueled fear, even if unintentionafly. They have tactically allied with political forces indifferent or hostile to HIV/AIDS care and to the people who are living with AIDS. Such tactics alienate the HIV-infected and affected communities, whose massive involvement in advocacy, prevention and social support has been a powerful engine of progress against HIV. Fundamentally, emphasizing named reporting diverts our attention from what would really work:

With treatment advances rendering AIDS ever more arbitrary, we do need expanded surveillance to monitor and plan. A non-name-based unique identifier system can meet this need, with only modest loss of efficiency. |

What do you think?

![]()

|

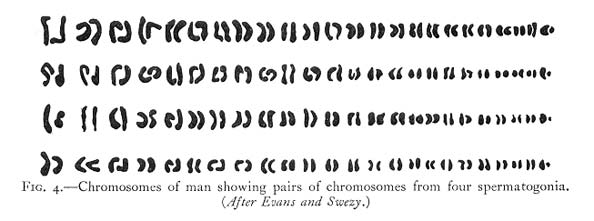

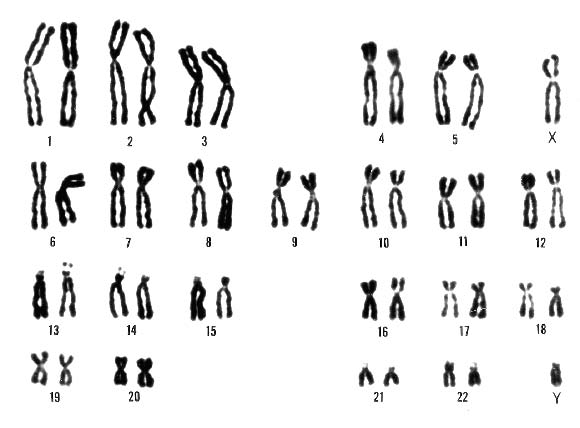

All Scientists Are Blind ... some years before [Peter Leavitt] had formulated the Rule of 48. The Rule of 48 was intended as a humorous reminder to scientists, and referred to the massive literature collected in the late 1940s and the 1950s concerning the human chromosome number. |

|

|

"Usually the number of chromosomes is constant in a given species, although it may vary between different species even of the same genus. In man the chromosome number is forty-eight...." [Human Genetics and its Social Import, by S. J. Holmes (1936), p. 8. The illustration above appears on p. 9.]

"... the number of chromosomes is in general constant for any given species. Thus in each cell of a human being there are 48 chromosomes (24 pairs)...." [Principles of Heredity, 3rd. ed., by Laurence R. Snyder (1946), p. 26.] |

|

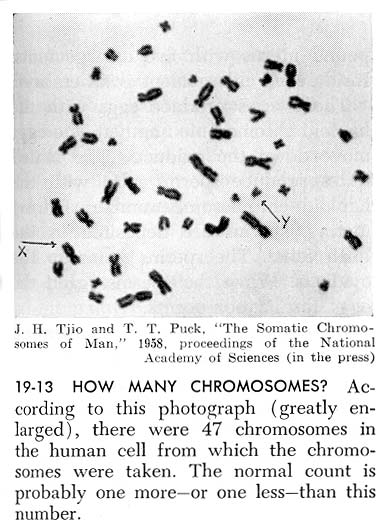

Exploring Biology: The Science of Living Things, 5th ed., by Ella Thea Smith (1959), p. 503. An additional note on this page reads: "Improved methods of counting chromosomes seem to indicate that the diploid number in man may be 46 rather than 48." |

|

"If you learned your biology a long time ago, you learned that men have forty-eight [chromosomes]--but the number has now been revised downward to forty-six (twenty-three pairs)." [The Language of Life: An Introduction to the Science of Genetics, by George and Muriel Beadle (1966), p. 89.] |

When and how did the change in the count of human chromosomes take place? Here's a first hand account from biologist, Maj Hultén, who was then an undergraduate student in Stockholm:

from "Numbers, bands and recombination of human chromosomes: Historical anecdotes from a Swedish student," by M. A. Hultén, in Cytogenetic and Genome Research 96: 14-19 (2002), pp. 15-16. |

Need for a New Model for Epidemic Management? |

Twentieth century model for epidemic management:

Has this paradigm outlived its usefulness? Alternatives:

|

Epidemiologists

Is total objectivity esssential? What are the costs and benefits of objectivity in such an enterprise? Do the needs of the many outweigh the needs of the few? When and how should public and/or private agencies provide for common services:

|

| How do historic epidemics compare with those today?

How does the incidence of plague alter the social, political, economic, and moral fabric of affected communities? How do individuals cope with the added stress in their daily lives? What happens to accepted systems of explanation and belief in the face of such challenges? Who will write the tales of the plagues of our time? How might readers five hundred or a thousand years from now respond to them? |

|

More Beasts for Worse Children

|

|

| Go to: |

|

|