| Chap. IV. General Despondency...

The consternation of the people of Philadelphia at this period was carried

beyond all bounds. Dismay and affright were visible in almost every

person's countenance. Most of those who could by any means make it

convenient, fled from the city. Of those who remained, many shut

themselves up in their houses, and were afraid to walk the streets.

The smoke of tobacco being regarded as a preventative, many persons, even

women and small boys, had segars [cigars] almost

constantly in their mouths. Others placing full confidence in garlic,

chewed it almost the whole day; some kept it in their pockets and shoes.

Many were afraid to allow the barbers or hair-dressers to come near

them, as instances had occurred of some of them having shaved the dead -- and

many having engaged as bleeders. Some, who carried their caution

pretty far, bought lancets for themselves, not daring to be bled with the

lancets of the bleeders. Many houses were hardly a moment in the

day free from the smell of gunpowder, burned tobacco, nitre, sprinkled

vinegar, &c.

Some of the churches were almost deserted, and others wholly closed.

The coffee house was shut up, as was the city library, and most of the

public offices -- three out of the four daily papers were discontinued, as

were some of the others.

Many were almost incessantly employed in purifying, scouring, and whitewashing

their rooms. Those who ventured abroad, had handkerchiefs or sponges

impregnated with vinegar or camphor at their noses, or smelling-bottles

full of the thieves' vinegar. Others carried pieces of tarred rope

in their hands or pockets, or camphor bags tied round their necks.

The corpses of the most respectable citizens, even of those who did

not die of the epidemic, were carried to the grave, on the shafts of a

chair, the horse driven by a negro, unattended by a friend or relation,

and without any sort of ceremony. People hastily shifted their course

at the sight of a hearse coming towards them. Many never walked on

the foot path, but went into the middle of the streets, to avoid being

infected in passing by houses wherein people had died.

Acquaintances and friends avoided each other in the streets, and only

signified their regard by a cold nod. The old custom of shaking hands

fell into such general disuse, that many shrunk back with affright at even

the offer of the hand. A person with a crape, or any appearance of

mourning, was shunned like a viper. And many valued themselves highly

on the skill and address with which they got to windward of every person

whom they met.

Indeed it is not probable that London, at the last stage of the plague,

exhibited stronger marks of terror, than were to be seen in Philadelphia,

from the 25th or 26th of August, till pretty late in September. When

people summoned up resolution to walk abroad, and take the air, the sick

cart conveying patients to the hospital, or the hearse carrying the dead

to the grave, which were travelling almost the whole day, soon damped their

spirits, and plunged them again into despondency.

While affairs were in this deplorable state, and people at the lowest

ebb of despair, we cannot be astonished at the frightful scenes that were

acted, which seemed to indicate a total dissolution of the bonds of society

in the nearest and dearest connexions. Who, without horror, can reflect

on a husband, married perhaps for twenty years, deserting his wife in the

last agony -- a wife unfeelingly abandoning her husband on his death bed -- parents

forsaking their only children -- children ungratefully flying from their parents,

and resigning them to chance, often without an enquiry after their health

or safety -- masters hurrying off their faithful servants to Bushhill, even

on suspicion of the fever, and that at a time, when, like Tartarus, it

was open to every visitant, but never returned any -- servants abandoning

tender and human masters who only wanted a little care to restore them

to health and usefulness --who, I say, can think of these things without

horror?

Yet they were daily exhibited in every quarter of our city; and such

was the force of habit, that the parties who were guilty of this cruelty,

felt no remorse themselves -- nor met with the execration from their fellow-citizens,

which such conduct would have excited at any other period. Indeed,

at this awful crisis, so much did self appear to engross the whole attention

of many, that less concern was felt for the loss of a parent, a husband,

a wife, or an only child, than, on other occasions, would have been caused

by the death of a servant, or even a favorite lap-dog.... |

|

Chap. V. Distress Increases...

Never, perhaps, was there a city in the situation of Philadelphia at this

period. The president of the United States [George

Washington] according to his annual custom, had removed to Mount

Vernon with his household. [From 1790 to 1800, Philadelphia

served as the seat of national government for the United States.

When the first census was taken in 1790, Philadelphia ranked as the new

nation's most populous city with nearly 43,000 residents.]

Most, if not all of the other officers of the federal government were absent.

The governor, who had been sick, had gone, by directions of his physician,

to his country seat near the falls of the Schuylkill [pronounced

SKOO-kle]--and nearly the whole of the officers of the state had

likewise retired. The magistrates of the city, except the mayor,

and John Barclay, esq. were away.... In fact, government of every

kind was almost wholly vacated, and seemed, by tacit, but universal consent,

to be vested in the committee [of ten appointed citizens]. |

|

Chap. XIII. Disorder Fatal to the Doctors...

Rarely has it happened, that so large a proportion of the gentlemen of

the faculty have sunk beneath the labours of their very dangerous profession,

as on this occasion. In five or six weeks, exclusive of medical students,

no less than ten physicians have been swept off....

To the clergy it has likewise proved very fatal. Exposed, in the

exercise of the last duties to the dying, to equal danger with the physicians,

it is not surprising that so many of them have fallen....

Among the women, the mortality has not by any means been so great, as

among the men, nor among the old and infirm as among the middle-aged and

robust.

To tipplers and drunkards, and to men who lived high, and were of a

corpulent habit of body, this disorder was very fatal....

To the filles do joie [prostitutes],

it has been equally fatal....

To hired servant maids it has been very destructive....

It has been dreadfully destructive among the poor. It is very

probable, that at least seven eighths of the number of the dead, were of

that class....

The mortality in confined streets, small allies, and close houses, debarred

of a free circulation of air, has exceeded, in a great proportion, that

in the large streets and well-aired houses. In some of the allies,

a third or fourth of the whole of the inhabitants are no more....

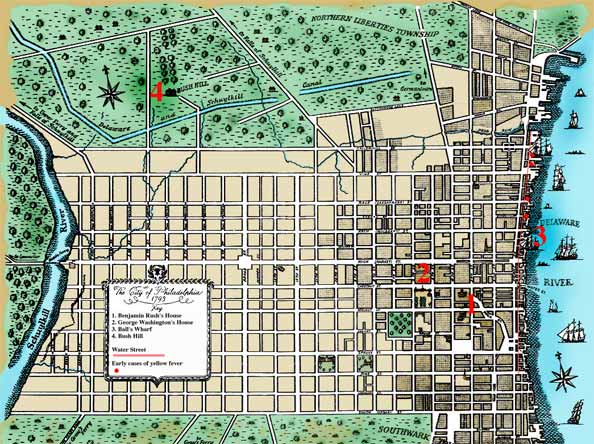

It is to be particularly remarked, that in general, the more remote the

streets were from Water street, the less they experienced of the calamity.

From the effects of this disorder, the French newly settled in Philadelphia,

have been in a very remarkable degree exempt. To what this may be

owing, is a subject deserving particular investigation. By some it

has been ascribed to their despising the danger. But, though this

may have had some effect, it will not certainly account for it altogether;

as it is well known that many of the most courageous persons in Philadelphia,

have been among its victims. By many of the French, the great fatality

of the disorder has been attributed to the vast quantities of crude and

unwholesome fruits brought to our markets, and consumed by all classes

of people.

When the yellow fever prevailed in South Carolina, the negroes, according

to that accurate observer, Dr. Lining, were wholly free from it.

"There is something very singular in the constitution of the negroes,"

says he, "which renders them not liable to this fever; for though many

of them were as much exposed as the nurses to this infection, yet I never

knew one instance of this fever among them, though they are equally subject

with the white people to the bilious fever." The same idea prevailed

for a considerable time in Philadelphia; but it was erroneous.

They did not escape the disorder; however, there were scarcely any of

them seized at first, and the number that were finally affected, was not

great; and as I am informed by an eminent doctor, "it yielded to the power

of medicine in them more easily than in the whites."

The error that prevailed on this subject had a very salutary effect;

for at an early period of the disorder, hardly any white nurses could be

procured; and, had the negroes been equally terrified, the sufferings of

the sick, great as they actually were, would have been exceedingly aggravated.

At the period alluded to, the elders of the African church met, and

offered their assistance tot he mayor, to procure nurses for the sick,

and to assist in burying the dead. Their offers were accepted; and

Absalom Jones, Richard Allen, and William Gray, undertook the management

of these two several services.

The great demand for nurses afforded an opportunity for imposition,

which was eagerly seized by some of the vilest of the blacks. They

extorted two, three, four, and even five dollars a night for such attendance,

as would have been well paid by a single dollar. Some of them were

even detected in plundering the houses of the sick. But it is unjust

to cast a censure on the whole for this sort of conduct, as many people

have done.... |

|

Chap. [XIV]. State of the Weather...

The weather, during the whole of the months of August and September, and

most part of October, was remarkably dry and sultry. Rain appeared

as if entirely at an end. Various indications, which in scarcely

any former instance had ever failed to produce wet weather, disappointed

the expectations, the wishes, and the prayers of the citizens.

The disorder raged with increased violence as the season advanced towards

the fall months. The mortality was much greater in September, than

in August -- and still greater in the beginning and till the middle of October,

than in September. It very particularly merits attention, that though

nearly all the hopes of the inhabitants rested on cold and rain, especially

the latter, yet the disorder died away with hardly any rain, and a very

moderate degree of cold. Its virulence may be said to have expired

on the 23d, 24th, 25th, and 26th of October. The succeeding deaths

were mostly of those long sick. Few persons took the disorder afterwards.

Those days were nearly as warm as many of the most fatal ones, in the middle

stage of the complaint, the thermometer being at 60, 59, 71, and 72.

To account for this satisfactorily is above our feeble powers. In

fact, the whole of the disorder, from its first appearance to its final

close, has set human wisdom and calculation at defiance.

The idea held up in the preceding paragraph, has been controverted by

many; and as the extinction of malignant disorders, generated in summer

or the early part of fall, has been universally ascribed to the severe

cold and heavy rains of the close of the fall, or the winter, it is asserted

that ours must have shared the same fate. It therefore becomes necessary

to state the reasons for the contrary opinion.

The extinction of these disorders, according to the generally-received

idea on this subject, arises from cold, or rain, or both together.

If from the former, how shall we account for a greater mortality in September,

than in August, whereas the degree of heat was considerably abated?

How shall we account for a greater mortality in the first part of October

than in September, although the heat was still abating? If rain be

the efficient cause of arresting the disorder, as is supposed by those

who attribute its declension to the rain on the evening of the 15th of

October, how shall we account for the inefficacy of a constant rain during

the whole terrible twelfth of October, when one hundred and eleven souls

were summoned out of this world, and a hundred and four the day following?

To make the matter more plain, I request the reader's attention to the

following statement:--

|