HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

1881-1885

prophylactic inoculation While studying the bacillus that causes chicken cholera, Louis Pasteur ran into a major research problem: cultivating the microbe in the lab seemed to weaken its virulence. Chickens injected with this weakened form of the microbe did not get sick! Pasteur obtained a fresh supply of bacteria from a naturally occurring outbreak of the disease. |

Louis Pasteur (1822-1895) |

||||||

| He injected these un-cultivated microbes into a new group of chickens as well as those that had not responded to the weakened microbes in earlier trials. To his surprise, only the new chickens succumbed to the disease while the previously injected chickens remained healthy. It had long been noted that recovery from certain diseases confers protection from future re-infection. But these chickens had never shown any signs of illness. Nevertheless, they clearly had become cholera-resistant. Pasteur concluded that injecting an individual with weakened microbes of a serious disease will artificially induce an effective immunity to that disease. Based on this principle, he developed the method of prophylactic inoculation (from the Greek words pro-, meaning "before," and phylassein, meaning "to guard") for the following diseases:

|

|||||||

Ilya Metchnikov (1845-1916) |

1883

phagocytosis Metchnikov observed that starfish larvae possess specialized cells that attack and envelop foreign matter that enters the organism. A colleague suggested the name phagocyte for these cells--from the Greek words phagein, meaning "to eat" and kytos, meaning "a hollow" (cell). |

||||||

| Metchnikov noted the similarities between the behavior of these starfish cells and that of the white cells in human blood. He suggested that white blood cells were phagocytic agents that serve to protect the body from invading microbes. | |||||||

|

1888-1890

bacterial toxins Diphtheria is a deadly disease. In addition to weakness and fever, symptoms can include the formation of a leathery membrane in the nose or throat, hence its name--from the Greek word diphthera, meaning "leather." Emile Roux and Alexandre Yersin worked with Pasteur at his Institute in Paris. In their study of the diphtheria bacillus, they discovered that the microbe itself does not cause the disease's symptoms. In fact, some individuals can harbor and transmit diphtheria bacilli while showing no signs of the illness at all. Roux and Yersin found that diphtheria's symptoms are the body's response to a toxin given off by the bacteria. [We now know that production of this toxin is stimulated when the bacteria themselves become infected by a virus. Once infected, diphtheria bacilli emit a powerful neurotoxin that is capable of paralyzing vital muscles like the heart and diaphgragm.] |

|

||||||

| Roux and Yersin's discovery launched a two-pronged approach to controlling diphtheria's spread: the search for both an antitoxin--a substance capable of counteracting and defusing the toxin's deadly effects--and a vaccine. | |||||||

Factors that generated concern for improving the public health:

|

Problems tackled by public health advocates: Child welfare

|

||

|

Hermann Biggs, (1859-1923) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

*an estimated 40,000 of these deaths were caused by flu! |

|

~3 million |

|

|

~3.5 million (1960-1975) |

|

|

Congo (1998-2005) |

~3.8 million |

|

| Genocide: | ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

| ||

|

|

~630,000 |

|

(Sep 1918-Jun 1919) |

|

|

|

|

|

Influenza Pandemic -- 1918 |

|

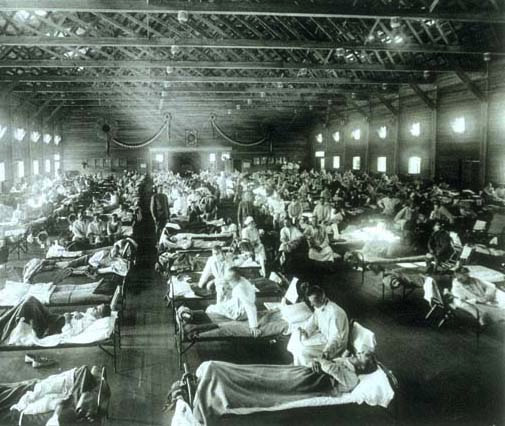

The first wave of the influenza epidemic began on Monday morning, March 11, 1918, at Camp Funston in Fort Riley, Kansas.  Between March and September 1918, sporadic outbreaks of deadly influenza broke out around the country, often among healthy young men at military bases or in prisons. |

|

March April May June July August

|

|

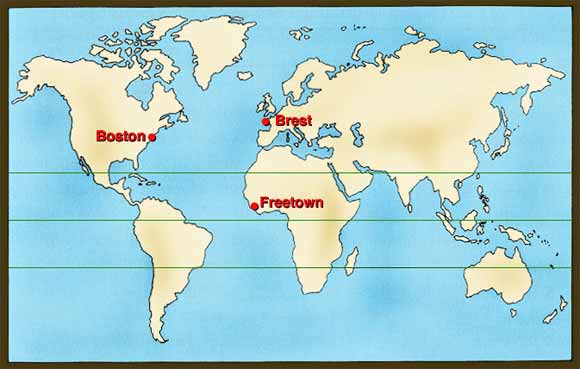

| In late August 1918, the pandemic virus mutated. The first victims of this new, more virulent form of influenza were stricken in three different and widely separated locations: Brest, France (August 22); Freetown, Sierra Leone (August 24); and Boston, Massachusetts (August 27). | |

|

|

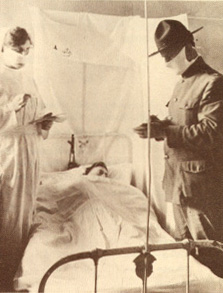

In September, a major outbreak of flu struck the men stationed at Camp Devens near Boston.

"I saw hundreds of young stalwart men in uniform coming into the wards of the hospital. Every bed was full, yet others crowded in. The faces wore a bluish cast; a cough brought up the blood-stained sputum. In the morning, the dead bodies are stacked about the morgue like cordwood." |

|

|

|

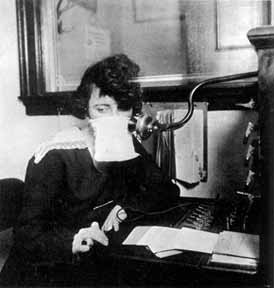

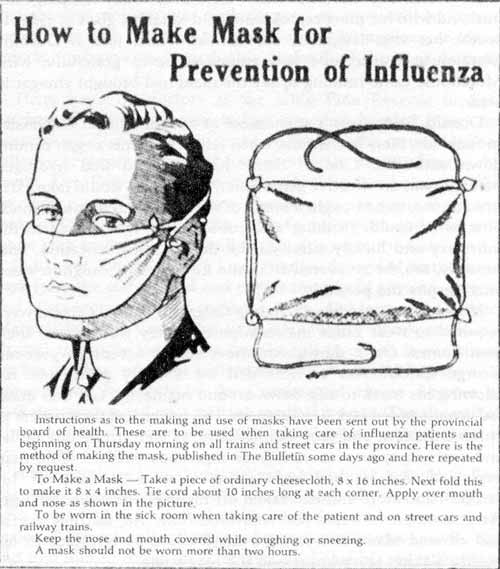

The public were encouraged to wear masks to prevent the spread of disease.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

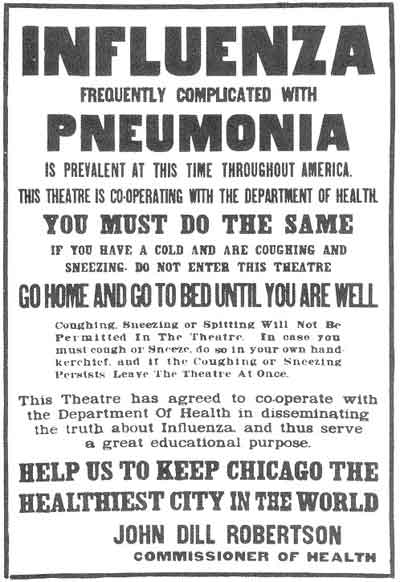

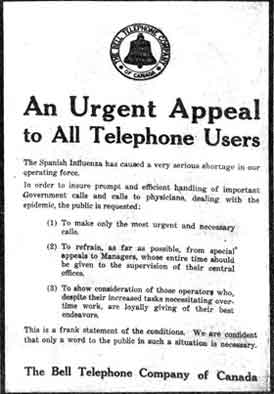

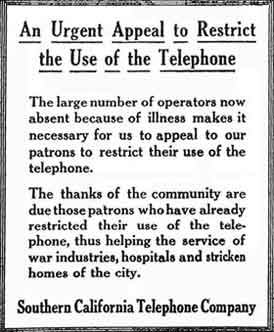

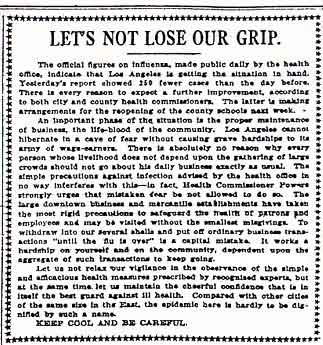

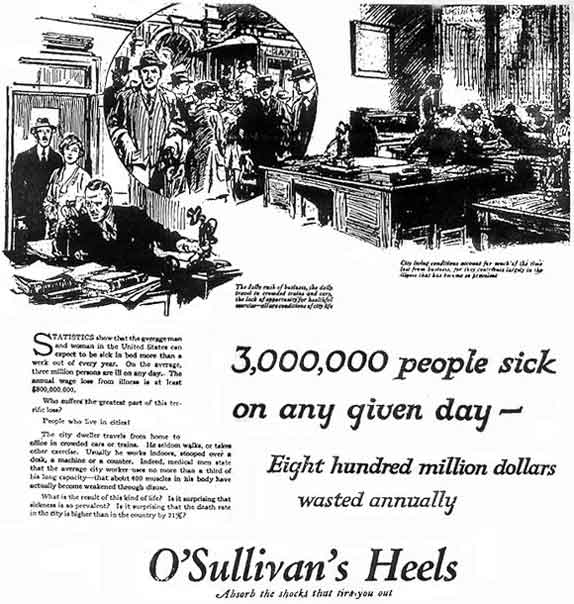

Public service announcements encouraged citizens to behave responsibly.  |

|

|

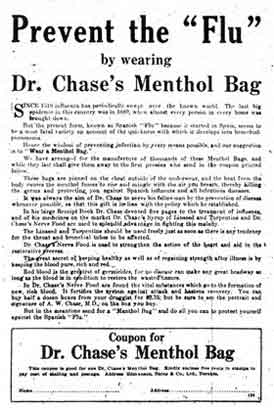

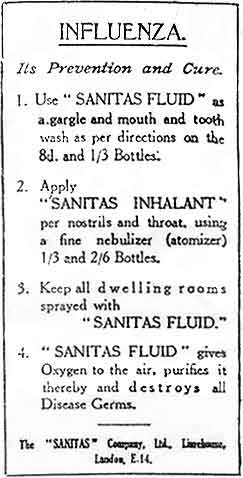

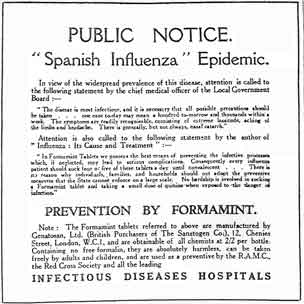

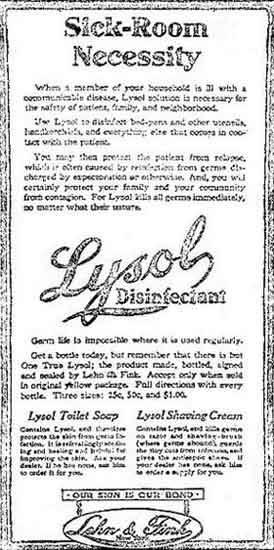

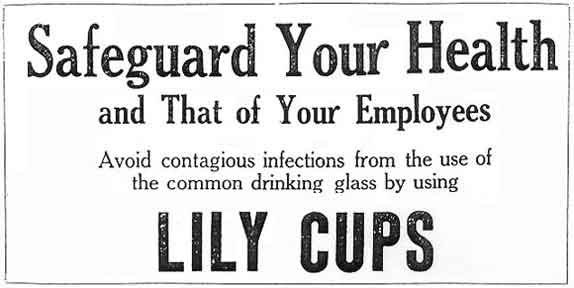

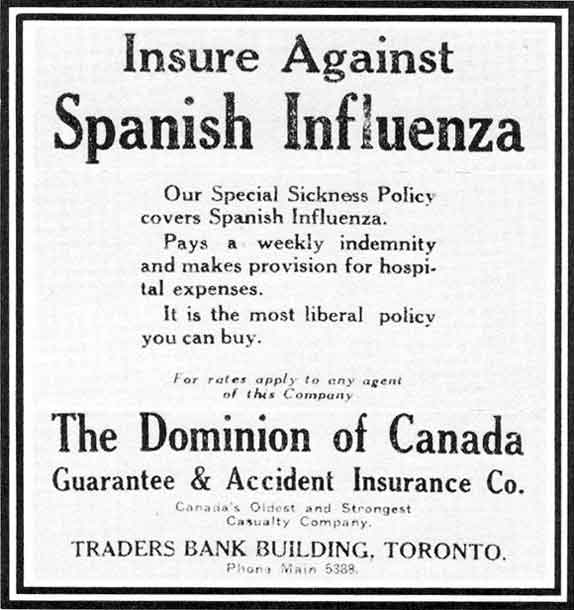

Many patent medicines were advertised as preventatives. |

|

|

|

|

Protective products were advertised.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Boston's Mayor, Andrew J. Peters is inoculated with a vaccine believed to protect against influenza. However, at the time, researchers did not have microscopes powerful enough to identify the flu virus responsible.

|

|

__________

In an average year, influenza causes about 17,000 deaths nationally. In pandemic years, this number is greatly increased:

I have just concluded a meeting on a subject of vast importance to all Americans. I have consulted with members of my Administration, with leading members of the health community, and with public health officials about the implications of this new appearance of swine flu.President Ford's announcement aroused considerable discussion in the press: |

| A well-known advantage of being President before a Presidential election

is the ability to use the office and its power to build a positive image

before the voters....

The President's medical advisers seem to have panicked and to have talked him into a decision based on the worst assumptions about the still poorly known virus and the best assumptions about the vaccine. --New York Times editorial, 6 April 1976 |

...not to proceed would represent an abrogation of reponsibility to the

public health.

--Dr. Edwin Kilbourne, 14 April 1976 |

| [There are no] signs of a deadly major epidemic which would justify

the extraordinary program that President Ford--with the virtually unquestioning

acquiescence of Congress--set in motion....

[Other industrial nations see this] as another one of those incomprehensible American aberrations and overreactions that appear occasionally in political years. --New York Times editorial, 8 June 1976

|

[The Times has] assumed an awesome responsibility in its unmitigated

hostility [to the swine flu program].... [W]ill the Times be proud

of its role in stimulating public doubt and discrediting the motives of

those who ... have advocated strong affirmative action to control a pandemic

for the first time in history?

--Dr. Edwin Kilbourne, 9 August 1976 |

| July | outbreak of mysterious, deadly illness among American Legion conventioneers in Philadelphia |

| August | Congress passes Swine Flu program bill |

| Fall | cases of influenza fail to materialize

complications from flu vaccine result in deaths and paralysis from Guillain-Barré syndrome among those who have been vaccinated |

| November | National Immunization Conference |

| December | vaccination program is halted |

Contemporary cartoon critical of President Ford shown urging swine flu vaccination What role should scientific and medical experts play in advising government officials on matters of public health? How should government act in response to scientific and medical advice? Did the government over-react in the case of the Swine Flu threat in 1976? When, and how, and to what degree should the public be involved when the nation is confronted with the possibility of a massive outbreak of disease? |

|

| Go to: |

|

|