HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

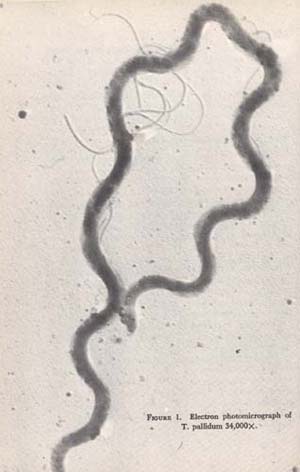

| Spirochete:

Treponema pallidum

|

|

Syphilis and the Syphilis-Like Diseases |

||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

| The spirochete is called Treponema... |

|

|

|

|

| [The spirochetes are identical even under the electron microscope; they differ mainly in the disease they produce in man and experimental animals. The Wassermann and other tests on serum, including specific tests, are positive in all, without differences. All are equally treatable with penicillin and other antibiotics.] | ||||

| Infection usually starts in... |

|

|

|

|

| but may

be congenital: |

|

|

|

|

| Transmitted by contact with, or between... |

|

|

|

|

| Individual sores are infectious for... |

|

|

|

|

| The sick person may transmit the disease for.... |

|

|

|

|

| Latency:

[symptoms disappear but may reappear later] |

|

|

|

|

| First sore is usually on... |

|

|

|

|

| Involvement of bone: |

|

|

|

|

| Involvement of heart, brain, and other organs: |

|

|

|

|

| Original environment: |

|

|

|

|

| Favoring climate

temperature: |

|

|

|

|

| humidity: |

|

|

|

|

The Course of the Disease |

|

| Primary venereal syphilis--

Within 3-4 weeks following contact, lesion, called a chancre, forms at the point of inoculation. Chancre grows over period of days or weeks from small pimple to size of marble. Breaks down on top and forms an ulcer. Lymph nodes in the groin become enlarged. Chancre heals completely, even without treatment. |

|

|

Secondary venereal syphilis--

About 6 weeks later, a generalized skin rash appears. This rash also heals without treatment. |

| Tertiary venereal syphilis--

A latent phase then ensues which may last from two to 20+ years. Preserved skull of a woman who died in 1796 showing the disfiguring effects of the disease in its tertiary phase. Lest you imagine that the 18th century drawing over-dramatizes the grotesque aspects of tertiary syphilis, compare it with a photograph taken of a modern day victim. |

|

Cures? |

When confronted by the challenge of treating this new disease, physicians turned to the theory of four humors. Too much phlegm was most often blamed for the pox. To reduce the excess phlegm physicians recommended a variety of treatments to promote spitting and/or sweating. But syphilis arrived in the Old World at a time when the unerring authority of Greek knowledge was under scrutiny. In Lecture 6 we introduced Paracelsus (1493-1541), the enigmatic German practitioner who questioned the idea that health and disease was a matter of a one-size-fits-all humoral balancing act. He wrote:

Paracelsus listed five principles or influences that can act alone or in complex combinations to cause disease:

To find an effective remedy for a patient's illness, Paracelsus told physicians to look beyond the obvious symptoms to the disease itself:

In Paracelsus's view, reducing a patient's excess phlegm would do little to cure the disease. "A good remedy was worth as much a thousand years ago as it is now," he wrote, "and a bad remedy was then as worthless as it is now.... The tares among the corn are as old as the corn, nevertheless, they cannot be used instead of the corn. In my opinion, the world should awaken to this fact, and because the good surpasses the bad in worth, we should abandon the bad...." A key element in Paracelsus's approach to health and disease was his belief that man is a microcosmic reflection of the macrocosm at large:

For this reason, remedies for what ails the world within us are to be found in the world around us:

To prescribe well, a physician must learn "where nature has her pharmacies, where her virtues have been written down, and in what boxes they are stored." Thus Paracelsus found nature's remedy for syphilis:

Paracelsus was not the only one advocating the use of mercury as a remedy for syphilis. It had served as the basis of medicines long used by Arab physicians to treat skin disorders and rashes. Mercury's use appealed to Galenists as well since it induces copious salivation (a classic sign of mercury poisoning) thus helping the patient to expel excess phlegm. |

Mercury and its Compounds

|

|

| Despite its reputation as a dangerous poison, mercury's ability to make patients sweat and salivate profusely encouraged medical practitioners to prescribe it as a treatment for syphilis: | |

|

|

Mercury metal • "quicksilver"

|

Mercuric oxide "red precipitate" •

|

|

|

|

Mercurous chloride • "calomel" |

|

Sinabar is a deadly medicine made halfe of quicksilver, and halfe of brimstone by Art of fire.... I know the abuse of these ... medicines hath done unspeakable harme in the common-wealth of England, and daily doth more and more, working the utter infamy and destruction of many an innocent, man, woman, and child.... [Nevertheless] The perfect cure proceeds from thee,

--The Surgeons Mate (1617) by John Woodall (c. 1556-1643) |

Mercuric sulfide

Cinnabar (mercuric sulfide) is a natural ore from which mercury can be readily obtained. |

|

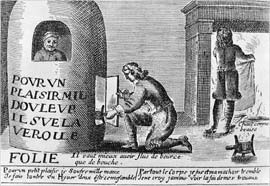

"For a little pleasure, a thousand pains" |

Fumigation Mercury (and other materials) were thrown onto charcoal to generate fumes to cause the patient to sweat out the pox's toxins. |

|

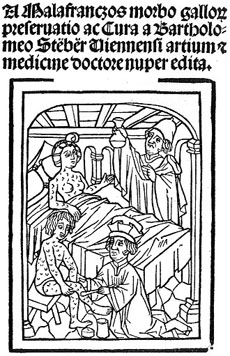

| Inunction Mercury mixed with honey, brandy, aloe, myrrh, sulfur, camphor, fried earthworms, ground live frogs ... (you name it) ... to make an ointment that could be applied topically to lesions and sometimes more generally to the skin Woodcut (1498), right: physician applies ointment (possibly a mercury-based compound) on pustules. |

|

|

|

Guaiacum Mercury's risks encouraged a search for alternatives. The bark of the guaiacum, a tree native to the West Indies, was introduced to Europe in 1519 by Ulrich von Hutten (1488-1523). Guaiacum was believed by many to be a good natural cure because the tree grew in the land where the disease was thought to have originated. Because it stimulated salivation and sweating when ingested, guaiacum bark was believed to be as effective as mercury, but without the dangerous side effects. |

|

Guaiacum flower |

Guaiacum fruit and seed |

|

Guaiacum trunk |

Guaiacum bark |

|

| I must now sing of the Gods' great gifts and of the sacred tree [guaiacum]

brought from an unknown world, which alone has moderated, relieved and

ended suffering....

Syphilis sive morbus Gallicus [Syphilis, or the French Disease]

(1530) by Girolamo Fracastoro (c.1478-1553)

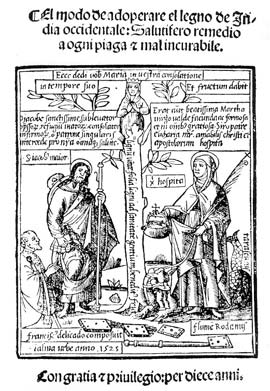

Woodcut, right: Title page illustration depicting guaiacum as the "tree of life [lignum vitae]; the leaves of the tree are for the health of the peoples; a blessed fruit" from pamphlet entitled "Concerning the way in which the wood from the West Indies may be prepared. It is a curative remedy for every plague and every incurable malady" (1529) by Francisco Delicado |

|

|

Guaiacum treatment

• break wood into small pieces or grind powder • mash 1 lb of wood with 8 lbs of water for a day and a night • simmer slowly in well-covered vessel filled 2/3 full • simmer till reduced by half (do NOT boil) • skim foam and apply to syphilitic sores • drink remaining liquid

Preparing and administering guaiacum. |

||

|

Tobacco being a common herbe, which (though under divers names)

growes almost every where, was first found out by some of the barbarous

Indians, to be a Preservative, or Antidot against the Pockes, a

filthy disease, whereunto these barbarous people are (as all men know)

very much subject, what through the uncleanly and adust [parched; sallow; melancholy] constitution of

their bodies, and what through the intemperate heate of their Climate:

so that as from them was first brought into Christendome, that most detestable

disease, so from them likewise was brought this use of Tobacco,

as a stinking and unsavourie Antidot, for so corrupted and execrable a

Maladie, the stinking Suffumigation whereof they yet use against that disease,

making so one canker or venime to eate out another.

A Counterblaste to Tobacco (1604) by King James I (1566-1625) |

|

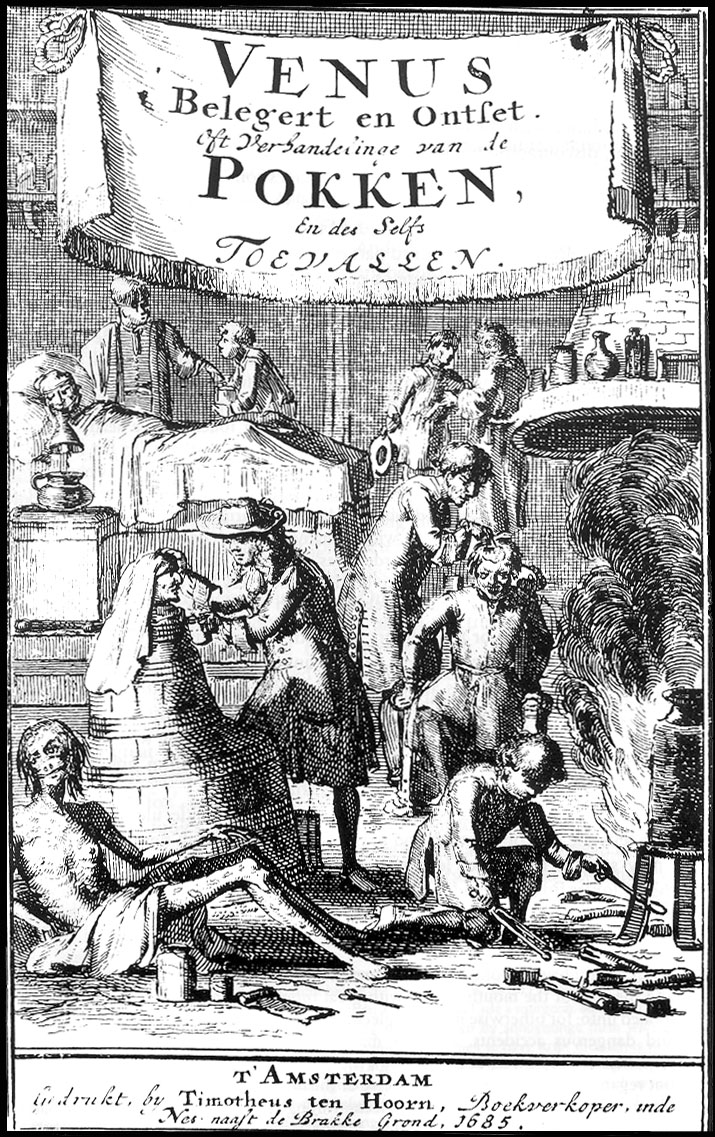

For centuries, mercury remained the treatment of choice for many medical practitioners (and charlatans).  Title page illustration from Venus Belegert en Ontset... (1685) by the Dutch physician, Steven Blanckaert (1650-1702). Physicians are pictured using a variety of methods to expose syphilitic patients to the healing effects of mercury. |

||

|

| Go to: |

|

|