HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

HISTORY 135F

Infectious and

Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

| "Tuberculosis" is a relatively modern name (first

appearing in print in the 1840s) for a very old disease. It comes

from the Latin word, tuberculum, meaning "protuberance, projection

or growth," and refers to the tumor-like nodules that victims often display.

In fact, until TB's bacterial agent was discovered in 1882, many physicians

thought TB's characteristic nodules and wasting identified it as a form

of cancer.

Patients suffering from TB exhibited many symptoms: evening fever, night sweats, blood spitting, weak pulse, diarrhea.... But the symptom that left the strongest impression was emaciation. It is this characteristic that formed the basis of TB's many names:

Tubercles varied in their consistency. They could be as hard as cartilage and bone, or crumbly like chalk. In some cases, they were found to be filled with pus having the consistency of cheese or honey. As anatomical information grew, so did physicians' questions about tubercles:

This changed with the introduction of two new diagnostic procedures:

Because the symptoms of tuberculosis were so varied and there was little agreement as to its cause (even after the tubercle bacillus was isolated by Robert Koch (1843-1910) in 1882, physicians treated their patients with an array of nonspecific healthful remedies: fresh air, sunshine, good nutrition, sufficient sleep, and exercise.

|

|

Edward Livingston Trudeau (1848-1915) was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1872. He decided to spend the little time he believed he had left in his life enjoying the wilderness. He went to Lake Saranac in the Adirondack Mountains of upstate New York. Instead of wasting away, however, Trudeau improved! He credited his newfound health to the environment at Lake Saranac.

Trudeau established a retreat there (Saranac Lake Sanatorium) so that other tuberculous patients might enjoy the benefits Saranac had to offer.

Lake Saranac, New York (1885) Patients could rest, recreate and restore their health at Saranac by adhering to a simple regimen: Before going to bed open the windows top and bottom, except in the severest weather, and even then have one window open at least a foot. Better still is sleeping in the open. Avoid exposure to a careless consumptive. Do not live in the same house, sleep in the same bed with some one known to be suffering with tuberculosis, or permit him to cough in your face. No Spitting. Sleep at least eight hours each night. The common towel must go. It is a disease spreader and in most cases

against the law.

I must

Patients breathe in fresh air while they relax in the snow at Lake Saranac. |

|

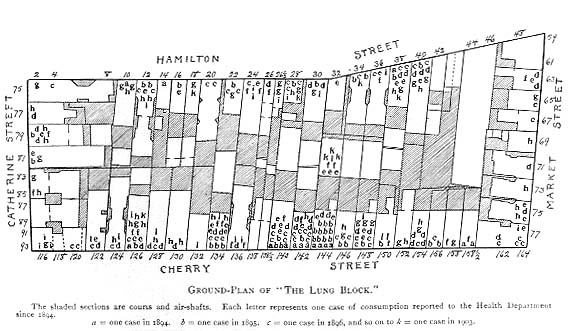

| Of course, only the wealthy could take advantage of Saranac's amenities. The poor were left to their own devices. One block in New York City's Lower East Side harbored so many cases of tuberculosis it was nicknamed "The Lung Block"! The spot map shown below (similar to John Snow's cholera map) records the geographic and temporal distribution of tuberculosis on this block. Shaded areas on the map are undeveloped land. White areas show the structures. Each lower-case letter within a building indicates a case of tuberculosis at that location: each "a" represents a case reported in 1894; each "b" stands for a case reported in 1895; and so on. |

|

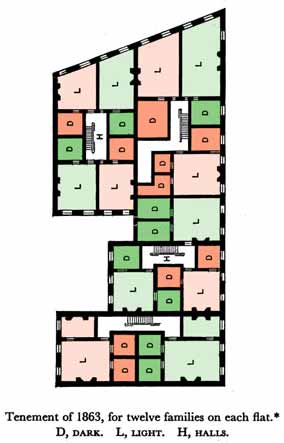

Seen from overhead, this block of tenements might look something like this:

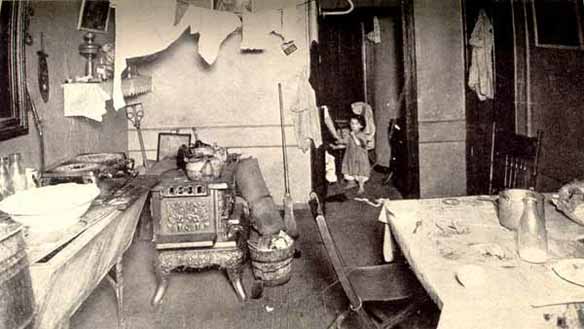

Seen from inside, a tenement room might look something like this: |

|

| Most rooms had no windows, and little or no ventilation: |  |

|

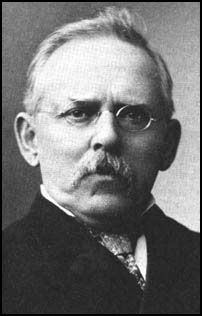

Social reformer, Jacob Riis (1849-1914) documented the squalor of New York City's tenements in words and photographs. |

"The Awakening" from How the Other Half Lives by Jacob Riis THE dread of advancing cholera, with the guilty knowledge of the harvest field that awaited the plague in New York's slums, pricked the conscience of the community into action soon after the close of the war. A citizens' movement resulted in the organization of a Board of Health and the adoption of the "Tenement-House Act" of 1867, the first step toward remedial legislation. A thorough canvass of the tenements had been begun already in the previous year; but the cholera first, and next a scourge of small-pox, delayed the work, while emphasizing the need of it, so that it was 1869 before it got fairly under way and began to tell. The dark bedroom fell under the ban first. In that year the Board ordered the cutting of more than forty-six thousand windows in interior rooms, chiefly for ventilation--for little or no light was to be had from the dark hallways. Air-shafts were unknown. The saw had a job all that summer; by early fall nearly all the orders had been carried out. Not without opposition; obstacles were thrown in the way of the officials on the one side by the owners of the tenements, who saw in every order to repair or clean up only an item of added expense to diminish their income from the rent; on the other side by the tenants themselves, who had sunk, after a generation of unavailing protest, to the level of their surroundings, and were at last content to remain there. The tenements had bred their Nemesis, a proletariat ready and able to avenge the wrongs of their crowds. Already it taxed the city heavily for the support of its jails and charities. The basis of opposition, curiously enough was the same at both extremes; owner and tenant alike considered official interference an infringement of personal rights, and a hardship. It took long years of weary labor to make good the claim of the sunlight to such corners of the dens as it could reach at all. Not until five years after did the department succeed at last in ousting the "cave-dwellers" and closing some five hundred and fifty cellars south of Houston Street, many of them below tide-water, that had been used as living apartments. In many instances the police had to drag the tenants out by force. The work went on; but the need of it only grew with the effort. The Sanitarians were following up an evil that grew faster than they went; like a fire, it could only be headed off, not chased, with success. Official reports, read in the churches in 1879, characterized the younger criminals as Victims of low social conditions of life and unhealthy, overcrowded lodgings, brought up in "an atmosphere of actual darkness, moral and physical." This after the saw had been busy in the dark corners ten years! "If we could see the air breathed by these poor creatures in their tenements," said a well-known physician, "it would show itself to be fouler than the mud of the gutters." Little improvement was apparent despite all that had been done. "The new tenements, that have been recently built, have been usually as badly planned as the old, with dark and unhealthy rooms, often over wet cellars, where extreme overcrowding is permitted," was the verdict of one authority. These are the houses that to-day perpetuate the worst traditions of the past, and they are counted by thousands. The Five Points had been cleansed, as far as the immediate neighborhood was concerned, but the Mulberry Street Bend was fast outdoing it in foulness not a stone's threw away, and new centres of corruption were continually springing up and getting the upper hand whenever vigilance was relaxed for ever so short a time. It is one of the curses of the tenement-house system that the worst houses exercise a levelling influence upon all the rest, just as one bad boy in a schoolroom will spoil the whole class. It is one of the ways the evil that was "the result of forgetfulness of the poor," as the Council of Hygiene mildly put it, has of avenging itself. The determined effort to head it off by laying a strong hand upon the tenement builders that has been the chief business of the Health Board of recent years, dates from this period. The era of the air-shaft has not solved the problem of housing the poor, but it has made good use of limited opportunities. Over the new houses sanitary law exercises full control. But the old remain. They cannot be summarily torn down, though in extreme cases the authorities can order them cleared. The outrageous overcrowding, too, remains. It is characteristic of the tenements. Poverty, their badge and typical condition, invites--compels it. All efforts to abate it result only in temporary relief. As long as they exist it will exist with them. And the tenements will exist in New York forever. To-day, what is a tenement? The law defines it as a house "occupied by three or more families, living independently and doing their cooking on the premises; or by more than two families on a door, so living and cooking and having a common right in the halls, stairways, yards, etc." That is the legal meaning, and includes flats and apartment-houses, with which we have nothing to do. In its narrower sense the typical tenement was thus described when last arraigned before the bar of public justice: "It is generally a brick building from four to six stories high on the street, frequently with a store on the first floor which, when used for the sale of liquor, has a side opening for the benefit of the inmates and to evade the Sunday law; four families occupy each floor, and a set of rooms consists of one or two dark closets, used as bedrooms, with a living room twelve feet by ten. The staircase is too often a dark well in the centre of the house, and no direct through ventilation is possible, each family being separated from the other by partitions. Frequently the rear of the lot is occupied by another building of three stories high with two families on a floor." The picture is nearly as true to-day as ten years ago, and will be for a long time to come. The dim light admitted by the air-shaft shines upon greater crowds than ever. Tenements are still "good property," and the poverty of the poor man his destruction. A barrack down town where he has to live because he is poor brings in a third more rent than a decent flat house in Harlem. The statement once made a sensation that between seventy and eighty children had been found in one tenement. It no longer excites even passing attention, when the sanitary police report counting 101 adults and 91 children in a Crosby Street house, one of twins, built together. The children in the other, if I am not mistaken, numbered 89, a total of 180 for two tenements! Or when a midnight inspection in Mulberry Street unearths a hundred and fifty "lodgers" sleeping on filthy floors in two buildings. Spite of brown-stone trimmings, plate-glass and mosaic vestibule floors, the water does not rise in summer to the second story, while the beer flows unchecked to the all-night picnics on the roof. The saloon with the side-door and the landlord divide the prosperity of the place between them, and the tenant, in sullen submission, foots the bills. Where are the tenements of to-day? Say rather: where are they not? In fifty years they have crept up from the Fourth Ward slums and the Five Points the whole length of the island, and have polluted the Annexed District to the Westchester line. Crowding all the lower wards, wherever business leaves a foot of ground unclaimed; strung along both rivers, like ball and chain tied to the foot of every street, and filling up Harlem with their restless, pent-up multitudes, they hold within their clutch the wealth and business of New York, hold them at their mercy in the day of mob-rule and wrath. The bullet-proof shutters, the stacks of hand-grenades, and the Gatling guns of the Sub-Treasury are tacit admissions of the fact and of the quality of the mercy expected. The tenements to-day are New York, harboring three-fourths of its population. When another generation shall have doubled the census of our city, and to that vast army of workers, held captive by poverty, the very name of home shall be as a bitter mockery, what will the harvest be? |

|

| Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)

chemist 1847: studied crystals 1864: studied fermentation

|

|

1871: each fermentation

involves different microbe

|

|

|

Joseph Lister (1827-1912)

concerned about post-surgery infection--"hospital gangrene" 1865: heard of Pasteur's work on microbes became determined to rid surgery of airborne disease causing agents found carbolic acid effective as disinfectant led to general acceptance of antiseptic surgery as standard practice

|

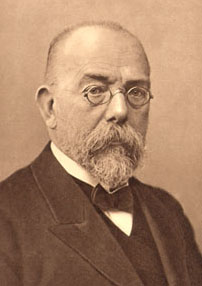

| Robert Koch (1843-1910)

developed new techniques of staining, incubating, and growing bacteria directed attention to microscopic world as site of influential yet invisible activity 1876: grew pure strain of

anthrax

bacillus

1882: isolated bacillus that causes TB |

|

|

1883: studied cholera

in India leading to discovery of microbe

1890: announced preparation of extract of TB bacilli called tuberculin; its use resulted in severe reactions and even death 1891: established Center for Infectious Disease 1905: awarded Nobel prize for work on TB |

|

|

| Go to: |

|

|