University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Week 4. Heavenly Reading Principles of Philosophy (1644)

|

1. Each and every thing, in so far as it can, always continues in the same state; and thus what is once in motion always continues to move.

2. All motion is in itself rectilinear; and hence any body moving in a circle always tends to move away from the center of the circle which it describes.

3. If a body collides with another body that is stronger than itself,

it loses none of its motion; but if it collides with a weaker body, it

loses a quantity of motion equal to that which it imparts to the other

body.

Part Three: The Visible Universe

15. The observed motions of the planets may be explained by various hypotheses.

When a sailor on the high seas in calm weather looks out from his own ship and sees other ships a long way off changing their mutual positions, he can often be in doubt whether the motion responsible for this change of position should be attributed to this or that ship, or even to his own. In the same way, the paths of the planets, when seen from the earth, are of a kind which makes it impossible for us to know, simply on the basis of the observed motions, what proper motions should be attributed to any given body. And since their paths are very uneven and are very complicated, it is not easy to explain them except by selecting one pattern, among all those which can make their movements intelligible, and supposing the movements to occur in accordance with it. To this end, astronomers have produced three different hypotheses, i.e., suppositions, which are regarded not as being true, but merely as being suitable for explaining the appearances.

16. Ptolemy's hypothesis does not account for the appearances.

The first of these hypotheses is that of Ptolemy. Since this is in conflict with many observations made recently (especially the waxing and waning phases of light which are observed on Venus just as they are on the moon), it is now commonly rejected by all philosophers, and hence I will here pass over it.

17. There is no difference between the hypotheses of Copernicus and Tycho, if they are considered simply as hypotheses.

The second hypothesis is that of Copernicus and the third that of Tycho Brahe. These two, considered simply as hypotheses, account for the appearances in the same manner and do not differ greatly, except that the Copernican version is a little simpler and clearer. Indeed, Tycho would have had no occasion to change it, had he not been attempting to unfold the actual truth of things, as opposed to a mere hypothesis.

18. Tycho attributes less motion to the earth than Copernicus, if we go by what he actually says, but in reality he attributes more motion to it.

Copernicus had no hesitation in attributing motion to the earth, but Tycho wished to correct him on this point, regarding it as absurd from the point of view of physics, and in conflict with the common opinion of mankind. But he did not pay sufficient attention to the true nature of motion, and hence, despite his verbal insistence that the earth is at rest, in actual fact he attributed more motion to it than did Copernicus.

19. My denial of the earth's motion is more careful than the Copernican view and more correct than Tycho's view.

The only difference between my position and those of Copernicus and Tycho is that I propose to avoid attributing any motion to the earth, thus keeping closer to the truth than Tycho while at the same time being more careful than Copernicus. I will put forward the hypothesis that seems to be the simplest of all both for understanding the appearances and for investigating their natural causes. And I wish this to be considered simply as a hypothesis or supposition that may be false and not as real truth....

28. Strictly speaking, the earth does not move, any more than the planets, although they are all carried along by the heaven.

Here we must bear in mind what I said above about the nature of motion, namely that if we use the term "motion" in the strict sense and in accordance with the truth of things, then motion is simply the transfer of one body from the vicinity of the other bodies which are in immediate contact with it, and which are regarded as being at rest, to the vicinity of other bodies. But it often happens that, in accordance with ordinary usage, any action whereby a body travels from one place to another is called "motion"; and in this sense it can be said that the same things moves and does not move at the same time, depending on how we determine its location. It follows from this that in the strict sense there is no motion occurring in the case of the earth or even the other planets, since they are not transferred from the vicinity of those parts of the heaven with which they are in immediate contact, in so far as these parts are considered as being at rest. Such a transfer would require them to move away from all these parts at the same time, which does not occur. But since the celestial material is fluid, at any given time different groups, of particles move away from the planet with which they are in contact, by a motion which should be attributed solely to the particles, not to the planet. In the same way, the partial transfers of water and air which occur on the surface of the earth are not normally attributed to the earth itself, but to the parts of water and air which are transferred.

29. No motion should be attributed to the earth if "motion" is taken in the loose sense, in accordance with ordinary usage; but in this sense it is correct to say that the other planets move.

But if we construe "motion" in accordance with ordinary usage, then all the other planets, and even the sun and fixed stars should be said to move; but the same cannot without great awkwardness be said of the earth. For the common practice is to determine the position of the stars from certain sites on the earth that are regarded as being immobile: the stars are deemed to move in so far as they pass these fixed spots. This is convenient for practical purposes, and so is quite reasonable. Indeed all of us from earliest years have reckoned the earth to be not a globe but a flat surface, such that "up" and "down" are everywhere the same, and the four directions, east, west, south and north, are the same for any point on the surface; and we have all used these directions for specifying the location of any other body. But what of a philosopher who realizes that the earth is a globe contained in a fluid and mobile heaven, and that the sun and the fixed stars always preserve the same positions relative to each other? If he takes these bodies as immobile for the purpose of determining the earth's location, and thus asserts that the earth itself moves, his way of talking is quite unreasonable. First of all, location in the philosophical sense must be determined not by means of very remote bodies like the stars, but with reference to bodies which are contiguous with the body which is said to move. Secondly, if we allow ordinary usage, there is no reason for considering that it is the stars which are at rest rather than the earth, unless we believe that there are no other bodies beyond them from which they are receding, and with reference to which it can be said that they move but the earth is at rest (in the same sense as the earth is said to move with reference to the stars). Yet to believe this is irrational. For our mind is of such a nature as to recognize no limits in the universe, whoever considers the immensity of God and the weakness of our senses will conclude that it is much more reasonable to suspect that there may be other bodies beyond all the visible fixed stars; and that, with reference to these bodies, the earth may be said to be at rest, but all the stars may be said to be in simultaneous motion. This is surely more reasonable than supposing that there cannot possibly be any such bodies because the creator's power is so imperfect; for this must be the supposition of those who maintain in this way that the earth moves. And if, later on, to conform to ordinary usage, we appear to attribute motion to the earth, it should be remembered that this is an improper way of speaking--rather like the way in which we may sometimes say that passengers asleep on a ferry "move" from Calais to Dover, because the ship takes them there.

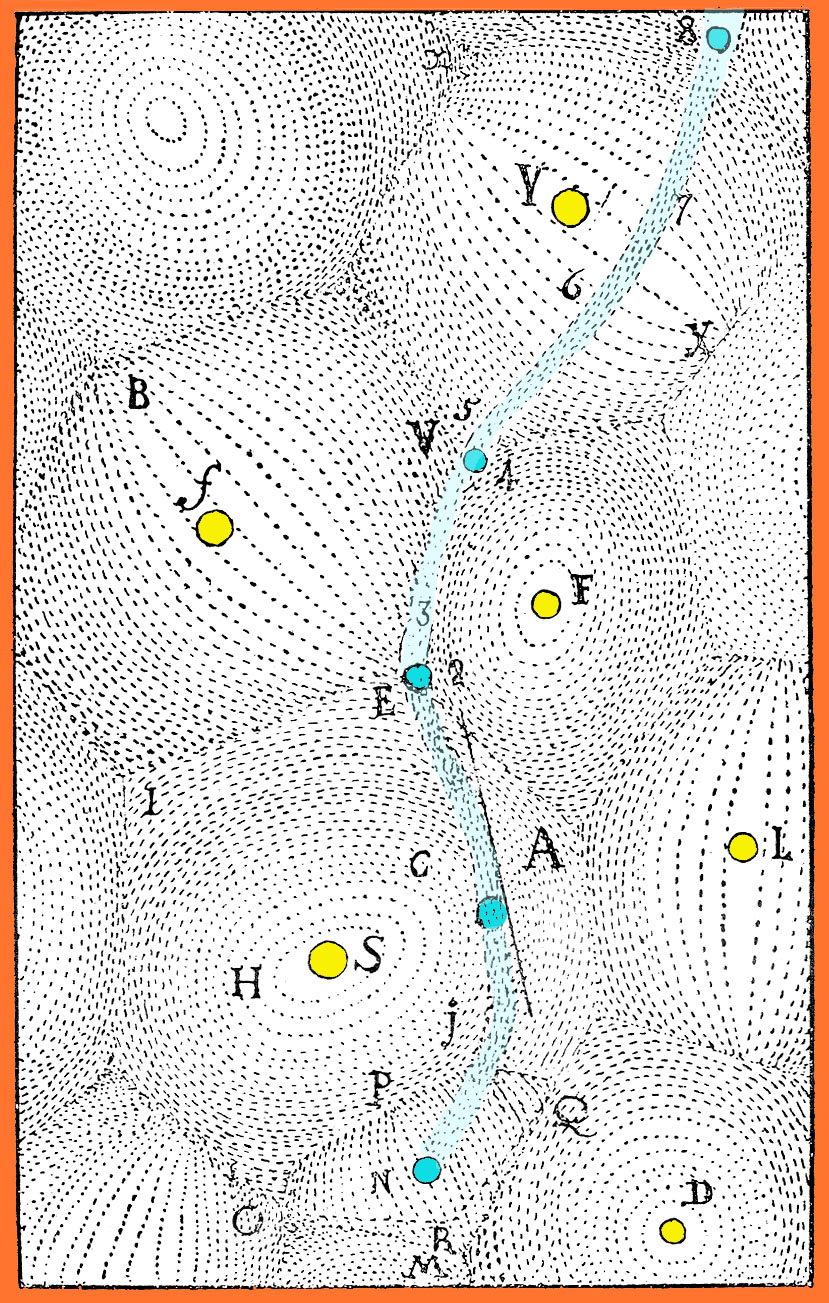

In Descartes' universe, every star (D, S, L, F, ƒ, Y) is surrounded by a swirling vortex of matter (including planets). In this illustration, a comet (N) moves like a leaf floating in a river, carried along the aetherial peripheries of these stellar vortices.

30. All the planets are carried round the sun by the heaven.

Let us thus put aside all worries regarding the earth's motion, and suppose that the whole of the celestial matter in which the planets are located turns continuously like a vortex with the sun at its center. Further, let us suppose that the parts of the vortex which are nearer the sun move more swiftly than the more distant parts, and that the planets (including the earth) always stay surrounded by the same parts of celestial matter. This single supposition enables us to understand all the observed movements of the planets with great ease, without invoking any machinery. In a river there are various places where the water twists around on itself and forms a whirlpool. If there is flotsam on the water we see it carried around with the whirlpool, and in some cases we see it also rotating about its own center; further, the bits which are nearer the center of the whirlpool complete a revolution more quickly; and finally, although such flotsam always has a circular motion, it scarcely ever describes a perfect circle but undergoes some longitudinal and latitudinal deviations. We can without any difficulty imagine all this happening in the same way in the case of the planets, and this single account explains all the planetary movements that we observe.

|