University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Quodlibet 5. You see what I'm saying...?

|

If any members of the Royal Society shall be curious

enough to try [my prism experiments], I should be very glad to be informed

with what success, so that if anything seems to be defective, or contrary

to this relation [between color and refraction], I may have an opportunity

of providing further directions, or of acknowledging my errors, if I have

committed any.

--Isaac Newton, 1672 |

In the mid-1660s, Isaac Newton performed many different experiments to study the dispersion of white light by a single glass prism. He purchased his prism at a country fair. Such fairs provided folks living outside large commercial centers with their principal opportunities to buy goods and supplies.

Newton's careful examination of the prism's spectrum convinced him that white light is a mixture of all visible colors. He knew it would be difficult to persuade others to accept this idea. Newton purchased a second prism, and undertook more extensive, more rigorous experiments on dispersion. When these two-prism experiments were complete, Newton felt sure that no one would be able to argue with his new theory on light and color. He called these experiments his "crucial" experiments because he was certain that anyone witnessing them would come away convinced his theory was correct.

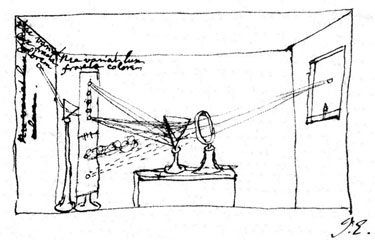

In his notebook, he drew a sketch showing one of his crucial prism experiments. In it, we see a sunbeam streaming through a hole in the window shutter on the right and falling on a prism. A spectrum appears on a screen in the middle of the room. The screen has a small slit in it that allows only the red portion of the spectrum to pass through. This red light then falls on a second prism positioned to the left of the screen. Only red light is seen emerging from the second prism.

In Newton's opinion, this experiment proved that prisms only transmit the colors that fall on them. If a prism converts ordinary sunlight into a rainbow of colors, then those colors must be in the sunlight to begin with. Here's how he explained it to Henry Oldenburg:

I concluded that the true cause of the length of the Spectrum is none other than that Light consists of Rays that are each refracted by a different amount.... Light is not simple or homogeneous, but consists of different Rays, some of which are refracted more than others. This is not because of any force exerted by the glass or any other cause, but from every particular Ray's natural tendency to experience a particular amount of Refraction.Read Newton's original description of his crucial experiment and the comments, questions, and criticisms it provoked in his contemporaries:

A Debate on the Nature of Light and Color

Reflect on a prepared science laboratory exercise you have done in

the past.

|

|