University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Quodlibet 2. Say what...?

|

[A]n excellent piece of work in one language cannot

be transferred into another as regards the peculiar quality that it possessed

in the former.... [L]et any one with an excellent knowledge of some

science like logic or any other subject at all strive to turn this into

his mother tongue, he will see that he is lacking not only in thoughts,

but words, so that no one will be able to understand the science so translated

as regards its potency....

--Roger Bacon (c.1210 - c.1292) |

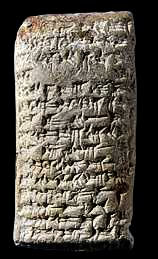

When we examine the written records our intellectual ancestors have left behind, we may find alien symbols forming alien words arranged in alien patterns.

Even familiar symbols and words create nagging contextual opacities.

|

bank paradigm fine St corn accident block F true kind |

We scratch our heads and wonder at the meaning of it all. The act of translation is both treacherous (that is, a seemingly safe activity containing hidden dangers) and traitorous (that is, faithless by its very nature).

Part 1 -- Lost or Found in Translation? |

Here's an example: eighteen lines from the epic De Rerum Natura, written around 50 BCE by the Roman poet, Lucretius. Its title is translated into English by some as On the Nature of Things, by others On the Nature of the Universe -- take your pick. The work, though originally written in verse, has been converted into prose by some translators. The original Latin text of these lines is provided below, followed by several English translations -- all the same, all different. Which do you find to be the most successful? Why? |

|

|

De Rerum Natura [On the Nature

of Things/the Universe] (c. 50 BCE)

by Titus Lucretius Carus (c. 96 - c. 55 BCE) Book IV, lines 467-485 nam nihil aegrius est quam res secernere apertas

Denique nil sciri siquis putat, id quoque nescit

Translated (c. 1675) by Lucy Hutchinson (1620-1681) For tis most noble to discerne betweene

Now if some say, that nothing's to be knowne,

Translated (1864) by Hugh Andrew Johnstone Munro (1819-1885) ... For nothing is harder than to separate manifest facts from doubtful which straightway the mind adds on of itself. Again if a man believe that nothing is known, he knows not whether this even can be known, since he admits he knows nothing. I will therefore decline to argue the case against him who places himself with head where his feet should be. And yet granting that he knows this, I would still put this question, since he has never yet seen any truth in things, whence he knows what knowing and not knowing severally are, and what it is that has produced the knowledge of the true and the false and what has proved the doubtful to differ from the certain. You will find that from the senses first has proceeded the knowledge of the true and that the senses cannot be refuted. For that which is of itself to be able to refute things false by true things must from the nature of the case be proved to have the higher certainty. Well then what must fairly be accounted of higher certainty than Sense? Shall reason founded on false sense be able to contradict them, wholly founded as it is on the senses? And if they are not true, then all reason as well is rendered false. Translated (1910) by Cyril Bailey (1871-1957) For nothing is harder than to distinguish things manifest from things uncertain, which the mind straightway adds of itself. Again, if any one thinks that nothing is known, he knows not whether that can be known either, since he admits that he knows nothing. Against him then I will refrain from joining issue, who plants himself with his head in the place of his feet. And yet were I to grant that he knows this too, yet I would ask this one question; since he has never before seen any truth in things, whence does he know what is knowing, and not knowing each in turn, what thing has begotten the concept of the true and the false, what thing has proved that the doubtful differs from the certain? You will find that the concept of the true is begotten first from the senses, and that the senses cannot be gainsaid. For something must be found with greater surety, which can of its own authority refute the false by the true. Next then, what must be held to be of greater surety than sense? Will reason, sprung from false sensation, avail to speak against the senses, when it is wholly sprung from the senses? For unless they are true, all reason too becomes false. translated (1916) by William Ellery Leonard (1876-1944) For naught is harder than to separate

Again, if one suppose

Translated (1951) by Ronald Edward Latham (1907-1992) There is nothing harder than to separate the facts as revealed from the questionable interpretations promptly imposed on them by the mind. If anyone thinks that nothing can be known, he does not know whether even this can be known, since he admits that he knows nothing. Against such an adversary, therefore, who deliberately stands on his head, I will not trouble to argue my case. And yet, if I were to grant that he possessed this knowledge, I might ask several pertinent questions. Since he has had no experience of truth, how does he know the difference between knowledge and ignorance? What has originated the concept of truth and faleshood? Where is his proof that doubt is not the same as certainty? You will find, in fact, that the concept of truth was originated by the senses and that the senses cannot be rebutted. The testimony that we must accept as more trustworthy is that which can spontaneously overcome falsehood with truth. What then are we to pronounce more trustworthy than the senses? Can reason derived from the deceitful senses be invoked to contradict them, when it is itself wholly derived from the senses? If they are not true, then reason in its entirety is equally false. Translated (1954) by Henri Clouard (1885-1973) Rien n'est plus difficile en effet que de faire le départ entre la vérité des choses et les conjectures qu l'esprit y ajoute de son propre fonds. Certains penseurs estiment que toute science est impossible; or ceux-là ignorent également si toute science est possible, puisqu'ils proclament ne rien savoir. Je n'accepte point de débat avec quiconque prétend marcher la tête en bas. Et quand bien même j'accorderais à ces gens quassurément l'on ne sait rien, je leur demanderais comment, n'ayant jamais trouvé la vérité, ils savent ce qu'est savoir et ne pas savoir, d'où ils tirent la notion du vrai et du faux et par quelle méthode ils distinguent le certain de l'incertain. Tu verras que les sens sont les premiers à nous avoir donné la notion du vrai et qui'ls ne peuvent être convaincus d'erreur. Car le plus haut degré de confiance doit aller à ce qui a le pouvoir de faire triompher le vrai du faux. Or quel témoignage a plus de valeur que celui des sens? Dira-t-on que si'ls nous trompent, c'est la raison qui aura mission de les contredire, elle qui est sortie d'eux tout enitière? Nous trompent-ils, alors la raison tout enitière est mensonge. Translated (1955) Alban Dewes Winspear (1899-1973) The hardest task of mind is just to separate

Translated (1963) by René Acuña (1929 - ) Porque no hay nada más difícil, que distinguir los datos reales, de las cosas dudosas que el ánimo pone antes de darnos cuenta completa. Para terminar, si alguno piensa que nada sabe, en consecuencia ignora la razón por que dice que nada se sabe. Pasaré por alto, pues, el entablar discusión con este que, en las bases de su doctrina, da las armas contra sí mismo. Y, sin embargo, aun concediéndole que sabe que no sabe, me gustaría preguntarle cómo sabe, si nunca ha visto en las cosas nada de verdad, lo que es saber o no saber; qué hecho ha originado la noción de lo verdadero y de lo falso, y qué criterio acostumbra para distinguir lo cierto de lo dudoso. Se encontrará con que la noción de lo verdadero ha nacido de los sentidos principalmente, y que los sentidos no pueden ser desmentidos. En efecto, debe gozar de mayor fe aquello que puede vencer los datos falsos con los hechos verdaderos. Y para eso, ¿quién es más digno de le que los sentidos? ¿En qué sentido falso apoyada podrá rechazarlos la razón, que nace toda ella de los sentidos? Porque, si los sentidos no son verdaderos, el juicio lógicamente es falso. Translated (1967) by Rolfe Humphries (1894-1969)

....Humankind

But if a man

Translated (1976) by Charles Hubert Sisson (1914-2003) Nothing is harder than to distinguish between

Anyone who thinks that nothing is known

Translated (1995) by Anthony Michael Esolen Nothing's as tough as to set things in plain sight,

And whoever thinks that knowledge can't be had

|

Part 2 -- Translation by [your name here] of Irvine |

| Imagine it is 2012 and you're now a distinguished

scholar who has been invited to "update" Thomas Kuhn's

Structure of

Scientific Revolutions for modern readers in a new fiftieth anniversary

special edition.

At the end of the first paragraph in chapter III, Kuhn wrote that in most cases: ...the paradigm functions by permitting the replication of examples any one of which could in principle serve to replace it. In a science, on the other hand, a paradigm is rarely an object for replication. Instead, like an accepted judicial decision in the common law, it is an object for further articulation and specification under new or more stringent conditions. How would you translate this into "English"? |

|