University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

|

|

Science moves from private space into the public arena. |

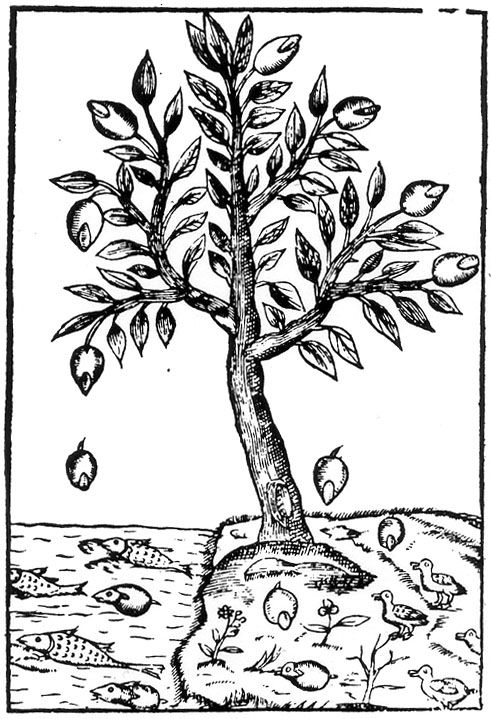

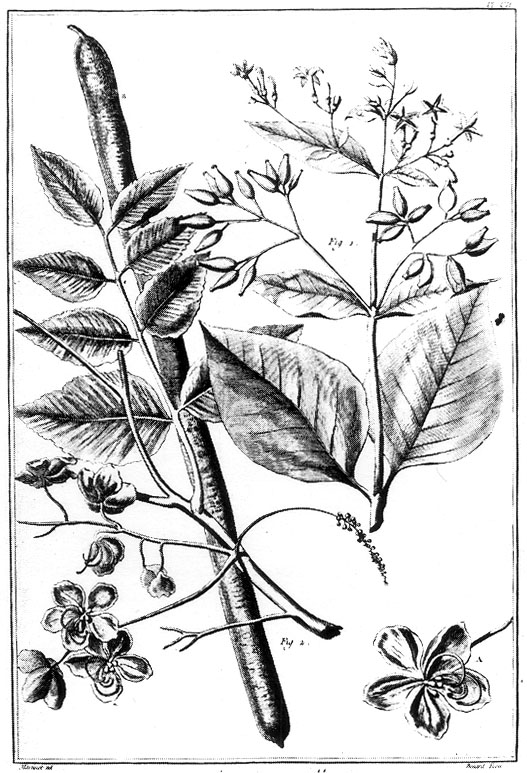

| Exploration of the new world stimulated interest in natural wonders. Eyewitnesses brought back reports of wondrous plants and animals. |

|

|

|

|

Changing Views of Knowledge |

When |

Who |

Where |

How |

Why |

| 400 BCE-500 CE | • philosophers | • academies • museums • libraries |

• critique and expand on work of predecessors | • intellectual gratification |

| 500-1450 | • learned professionals | • monasteries • universities |

• master work of predecessors | • explicate and glorify God's creation |

| 1450-1600 | • wealthy • powerful • virtuosi |

• private studies • patron's home |

• observe Nature directly | • personal and national benefit |

| 1600-1730 | • merchants • literati |

• scientific circles • learned societies |

• interrogate Nature | • acquire and disseminate useful knowledge |

A New Philosophy By the turn of the seventeenth century, an ever-widening group of people could and did read. Ready access to the world of ideas engendered a sense of intellectual restlessness and growing dissatisfaction with others' ideas about the world. Those with sufficient resources and leisure time, or who could locate a wealthy patron to support them, pursued philosophical ventures on their own and sought new ways of arriving at certain knowledge about the structure and working of the world. There were common threads running through these early efforts:

|

|

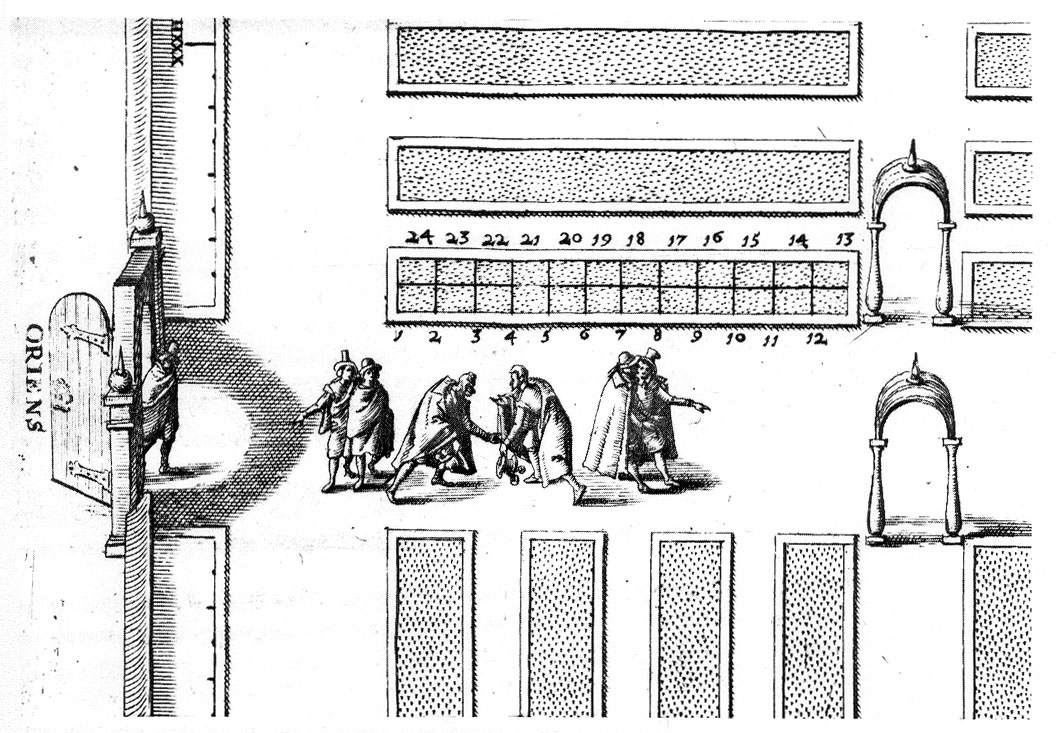

| Plant samples were collected and displayed in teaching gardens like the one at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands: |

|

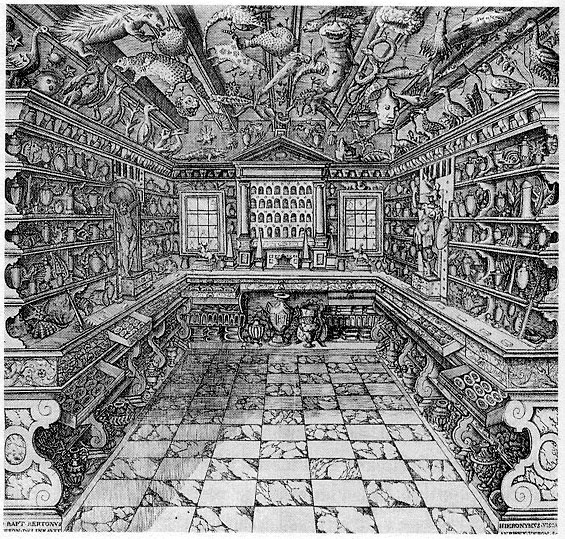

Rather than rely on pictures in books, students could see plants for themselves, examine their stems, leaves, flowers, and seeds and observe their growth and decay. Beautiful and/or intriguing objects, both natural and man-made, were collected by wealthy and worldly individuals who organized and displayed them privately in rooms called Kunstkammers or "cabinets of curiosities." |

The cabinet of pharmacist Francesco Calzolari (1522-1609)

at Verona, 1622

The cabinet of pharmacist Ferrante Imperato (1550-1631) at Naples, 1672 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) |

In the New Method, Bacon described the study of nature as a new kind of puzzle:

|

|

|

|

Those who have treated of the sciences have been either empirics or dogmatical. The former, like ants only heap up and use their store, the latter like spiders spin out their own webs. The bee, a mean between both, extracts matter from the flowers of the garden and the field, but works and fashions it by its own efforts.... The true labor of philosophy resembles [that of the bee], for it neither relies entirely nor principally on the powers of the mind, or yet lays up in the memory the matter afforded by the experiments of natural history and mechanics in its raw state, but changes and works it in the understanding.... [T]he reverence for antiquity, and the authority of men who have been esteemed great in philosophy ... have retarded men from advancing in science.... [B]y far the greatest obstacle to the advancement of the sciences ... is to be found in men's despair and the idea of impossibility.... [T]he secrets of nature betray thmselves more readily when tormented by art than when left to their own course.... [M]en will ... only begin to know their own power, when each person performs a separate part, instead of undertaking in crowds the same work. |

| In another book, The New Atlantis (1626), Bacon described an island utopia (Bensalem) which possessed an ideal research academy (Saloman's House) where New Method's principles were put into practice. |

|

|

The first half of the seventeenth century saw the formation of an increasing number of scientific groups formed to promote discussion and to disseminate the "new" philosophy. These were not merely groups of enthusiasts, but assemblies of individuals representing a broad cross-section of educated society. Many of them used Bacon's vivid description of Saloman's House as a model to organize their own "scientific societies." "Intelligentsers" encouraged and maintained active communication among widely-scattered virtuosi:

|

Italy Accademia dei Lincei [Academy of the Lynx-Eyed] (1603-1630)

Accademia del Cimento [Academy of Experiment] (1657-1667)

|

England Gresham College

I will and dispose, that ... the ... maior and corporation of [the City of London] ... shall give and distribute to and for the sustentation, mayntenaunce, and findinge foure persons from tyme to tyme to be chosen, nominated, and appointed ... to read the lectures of divynitye, astronomy, musicke, and geometry, within myne nowe dwellinge house in the parishe of St. Hellynes in Bishopsgate streete and St. Peeters the pore in the cittye of London ... the somme of two hundred pounds of lawfull money of England ... to every of the said readers for the tyme beinge the somme of fifty pounds of lawfull money of England yerely, for theire sallaries and stipendes, mete for foure sufficiently learned to read the said lectures....

"Invisible College" (1645-1660)

Our business was (precluding matters of theology and state affairs), to discourse and consider of Philosophical Enquiries, and such as related thereunto: as physic, anatomy, geometry, astronomy, navigation, statics, magnetics, chemics, mechanics, and natural experiments; with the state of these studies, as then cultivated at home and abroad. We then discoursed of the circulation of the blood, the valves in the veins, the venae lactae, the lymphatic vessels, the Copernican hypothesis, the nature of comets and new stars, the satellites of Jupiter, the oval shape (as it then appeared) of Saturn, the spots in the sun, and its turning on its own axis, the inequalities and selenography of the moon, the several phases of Venus and Mercury, the improvement of telescopes, and grinding of glasses for that purpose, the weight of air, the possibility, or impossibility of vacuities, and nature's abhorrence thereof, the Torricellian experiment in quicksilver, the descent of heavy bodies, and the degrees of acceleration therein; and divers other things of like nature. Some of which were then but new discoveries, and others not so generally known and embraced, as now they are, with other things appertaining to what has been called The New Philosophy, which from the times of Galileo at Florence, and Sir Francis Bacon (Lord Verulam) in England, has been much cultivated in Italy, France, Germany, and other parts abroad, as well as with us in England. Royal Society of London (1660- )

|

France Montmor Academy (1648-1664)

Académie des Sciences (1666- )

|

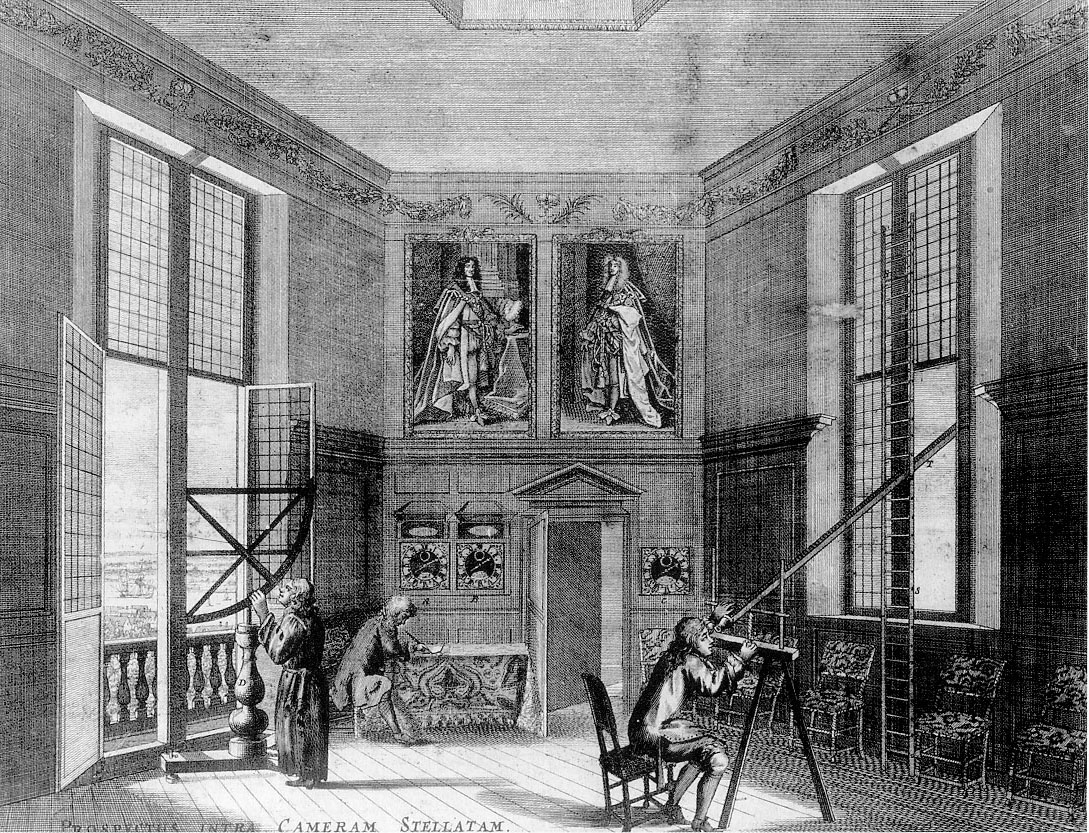

| By the second half of the seventeenth century, scientific societies had evolved. Participants aimed to develop the sciences rather than promote the new philosophy. The task of scientific societies was less to secure the scientific revolution than to maintain its momentum and reap its harvest. |

The New Philosophy engendered new patterns of social organization-- |

--with participants as seekers, probers, and witnesses.

|

|

|

--to measure Nature accurately so that patterns of small, but essential

differences could be identified.

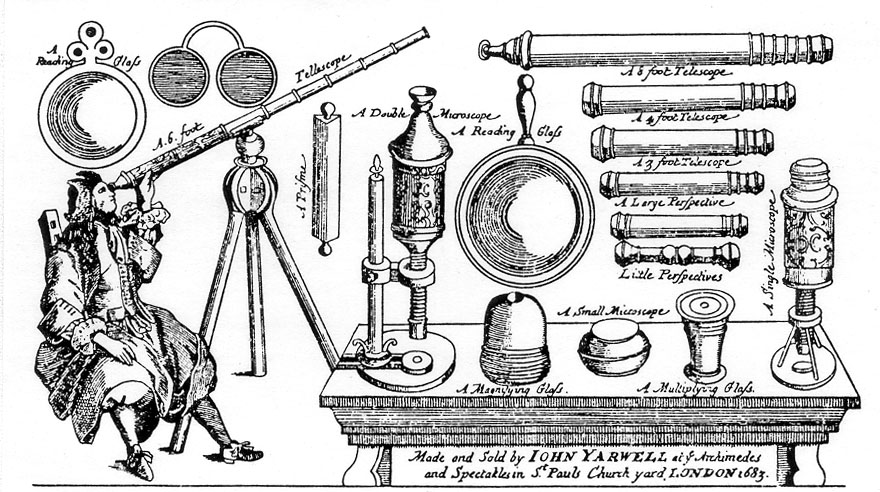

A seventeenth century optician advertises his wares: magnifying glasses, spectacles, telescopes, prisms, and microscopes. |

|

|

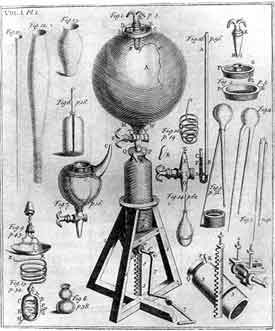

Pneumatics |

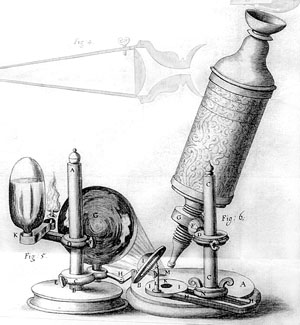

Optics |

|

|

|