University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Week 4. Heavenly Reading adapted excerpts from

|

Temporary Lightness

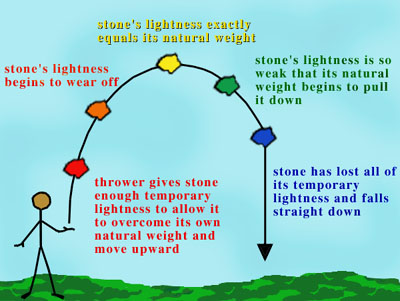

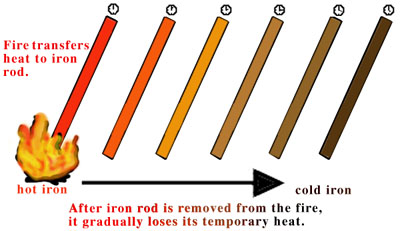

In order to explain my view on projectiles, let me first ask: What is the force that a thrower gives to a projectile? My answer is that it is a taking away of the heaviness when the body is hurled upward, and a taking away of a lightness when the body is hurled downward. If you're not surprised that fire can deprive iron of cold by introducing heat, you will not be surprised that a thrower can, by hurling a heavy body upward, deprive it of heaviness and render it light.

The body, then, is moved upward by the thrower so long as it is in his hand and is deprived of its weight. In the same way, the iron is made hot so long as it is in the fire and is deprived by it of its coldness.

Figure 1. Throwing a body upward gives it a temporary lightness.

The thrower's force, that is to say lightness, is kept in the stone when the thrower is no longer in contact just as heat is kept in the iron after the iron is removed from the fire.

Figure 2. Putting an iron rod in the fire gives it a temporary heat.

This force gradually diminishes in the projectile when it is no longer in contact with the thrower just as the heat diminishes in the iron when the fire is not present. The stone finally comes to rest just like the iron returns to its natural coldness.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Some people say that it is utterly ridiculous to suppose that a stone has become light during its upward motion. But their judgment of the situation is not based on careful and reasonable thinking. For I too would not say that a stone becomes permanently light when it is thrown. I would say rather that it retains its natural weight, just as the hot glowing iron has no coldness, but after the heat is used up, the iron resumes the same coldness that is its own. And there is no reason for us to be surprised that a stone, so long as it is moving upward, is light. In fact it would be impossible to find any difference between a stone moving upward and any other light body. For since we call things that move upward "light," and the thrown stone does move upward, the stone is therefore light so long as it moves upward.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Why Do Things Speed Up When They Fall?

The reason why the speed of natural motion is increased toward the end is certainly more difficult to discover than to explain. Either no one has thus far discovered it or, if at times someone has hinted at it, he has presented it in imperfect and defective form, and it has not been accepted by philosophers in general.

![]()

![]()

![]()

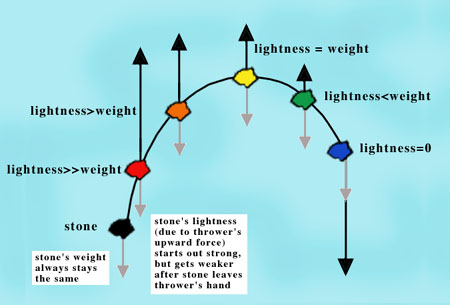

To move a heavy body upward, a thrower must apply a force greater than its resisting weight, otherwise he cannot overcome the resisting weight and the body will not move upward.

A body will move upward as long as the thrower gives it a force that is greater than the resisting weight. But since that force is continuously weakened the longer the body is away from the thrower's hand, it will finally become so diminished that it will no longer overcome the weight of the body and will not move the body upward beyond that point.

And yet this does not mean that at the body's ability to move will have been completely destroyed. It will just have been so diminished that it no longer exceeds the weight of the body, but is just equal to it. To put it in a word, the force that moves the body upward, which is lightness, will no longer be dominant in the body, but it will now be equal to the weight of the body. And at that time the body will be neither heavy nor light.

Figure 3. As temporary lightness wears off, a body will change its speed.

As the body's moving force continues to decrease, the weight of the body begins to win out, and the body begins to fall. Yet there still remains a considerable force that lifts the body upwards even though this force is no longer greater than the heaviness of the body. For this reason the essential weight of the body is diminished by this lightness and consequently the motion of falling is slower at the beginning. As the body's lightness continues to weaken, its weight is increased, and the body moves downward faster and faster.

This is what I consider to be the true cause of the acceleration of motion.

![]()

![]()

![]()

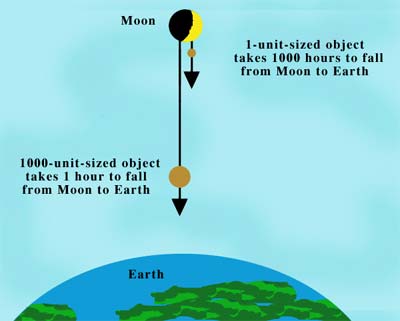

Do Large Things Fall Faster than Small Things?

Aristotle's idea that larger bodies fall faster than smaller bodies of the same material is completely ridiculous. Imagine that two lead balls--one a thousand times larger than the other--are dropped from the orbit of the Moon, and that it takes the larger ball one hour to land on Earth. Who would ever believe that the smaller one will take one thousand hours to get here?

Figure 4. Aristotle's "ridiculous" idea about falling bodies.

Or imagine that two stones, one twice the size of the other, are dropped from the top of a high tower at the same moment. Who would ever believe that the larger one will hit the ground while the smaller is only halfway down from the top of the tower?...

I will offer my own view which is based on reasoning rather than examples. Evidence that I am right will mean the collapse of Aristotle's view.

I say that all bodies made of the same material, even though they may differ in size, will still move with the same speed, and that a larger stone will not fall more swiftly than a smaller one....

![]()

![]()

![]()

Suppose that two bodies are equal and are very close to each other, all will agree that they will fall with equal speed.

Figure 5. Identical bodies fall with equal speed.

And if we imagine that they are joined together while moving, why, I ask, will they double the speed of their motion, as Aristotle held, or increase their speed at all?

Figure 6. Will the two joined bodies fall together at double the speed?

Scoffers who believe that they can defend Aristotle by using extreme examples just get themselves into deeper difficulty. Imagine if one of the bodies is a thousand times larger than the other. Surely these people must do some toiling and sweating before they can show that its velocity is a thousand times that of the other.

|