University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Week 9. Natural Selection adapted excerpts from

|

All ... is done by certain laws...

...[I]f we could suppose a number of persons of various ages presented to the inspection of an intelligent being newly introduced into the world, we cannot doubt that he would soon become convinced that men had once been boys, that boys had once been infants, and, finally, that all had been brought into the world in exactly the same circumstances.

Precisely thus, seeing in our astral system many thousands of worlds

in all stages of formation, from the most rudimental to that immediately

preceding the present condition of those we deem perfect, it is unavoidable

to conclude that all the perfect have gone through the various stages which

we see in the rudimental. This leads us at once to the conclusion

that the whole of our firmament was at one time a diffused mass of nebulous

matter, extending through the space which it still occupies. So also,

of course, must have been the other astral systems. Indeed, we must

presume the whole to have been originally in one connected mass, the astral

systems being only the first division into parts, and solar systems the

second.

A new solar system in the making? |

The first idea which all this impresses upon us is, that the formation of bodies in space is still and at present in progress. We live at a time when many have been formed, and many are still forming....

All, we see, is done by certain laws of matter, so that it becomes a question of extreme interest, what are such laws? All that can yet be said, in answer, is, that we see certain natural events proceeding in an invariable order under certain conditions, and thence infer the existence of some fundamental arrangement which, for the bringing about of these events, has a force and certainty of action similar to, but more precise and unerring than those arrangements which human society makes for its own benefit, and calls laws.

It is remarkable of physical laws, that we see them operating on every kind of scale as to magnitude, with the same regularity and perseverance. The tear that falls from childhood's cheek is globular, through the efficacy of that same law of mutual attraction of particles which made the sun and planets round.... There is, we might say, a sublime simplicity in this indifference of the grand regulations to the vastness or minuteness of the field of their operation. Their being uniform, too, throughout space, as far as we can scan it, and their being so unfailing in their tendency to operate ... afford to our minds matter for the gravest consideration.

Nor should it escape our careful notice that the regulations on which all the laws of matter operate, are established on a rigidly accurate mathematical basis. Proportions of numbers and geometrical figures rest at the bottom of the whole. All these considerations, when the mind is thoroughly prepared for them, tend to raise our ideas with respect to the character of physical laws, even though we do not go a single step further in the investigation. But it is impossible for an intelligent mind to stop there. We advance from law to the cause of law, and ask, What is that? Whence have come all these beautiful regulations?

Here science leaves us, but only to conclude, from other grounds, that there is a First Cause to which all others are secondary and ministrative, a primitive almighty will, of which these laws are merely the mandates. That great Being, who shall say where is his dwelling-place, or what his history! Man pauses breathless at the contemplation of a subject so much above his finite faculties, and only can wonder and adore!

CHAPTER 12

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS RESPECTING THE ORIGIN OF THE ANIMATED TRIBES.

[Natural law and the development of plants and animals: Geological evidence]

...If there is any thing more than another impressed on our minds by the course of the geological history, it is, that the same laws and conditions of nature now apparent to us have existed throughout the whole time, though the operation of some of these laws may now be less conspicuous than in the early ages, from some of the conditions having come to a settlement and a close.

It is scarcely less evident, from the geological record, that the progress of organic life has observed some correspondence with the progress of physical conditions on the surface....

In examining the fossils of the lower marine creation..., it is observed that some strata are attended by a much greater abundance of both species and individuals than others....

There are, indeed, abundant appearances as if, throughout all the changes of the surface, the various kinds of organic life invariably pressed in, immediately on the specially suitable conditions arising, so that no place which could support any form of organic being might be left for any length of time unoccupied. Nor is it less remarkable how various species are withdrawn from the earth, when the proper conditions for their particular existence are changed.... Not one species of any creature which flourished before the tertiary ... now exists; and of the mammalia which arose during that series, many forms are altogether gone, while of others we have now only kindred species....

...a somewhat different idea of organic creation...

A candid consideration of all these circumstances can scarcely fail to introduce into our minds a somewhat different idea of organic creation from what has hitherto been generally entertained. That God created animated beings, as well as the terraqueous theatre of their being, is a fact so powerfully evidenced, and so universally received, that I at once take it for granted. But in the particulars of this so highly supported idea, we surely here see cause for some re-consideration.

It may now be inquired,--In what way was the creation of animated beings effected? The ordinary notion may, I think, be not unjustly described as this,--that the Almighty author produced the progenitors of all existing species by some sort of personal or immediate exertion. But how does this notion comport with what we have seen of the gradual advance of species, from the humblest to the highest? How can we suppose an immediate exertion of this creative power at one time to produce zoophytes, another time to add a few marine mollusks, another to bring in one or two conchifers, again to produce crustaceous fishes, again perfect fishes, and so on to the end? This would surely be to take a very mean view of the Creative Power--to, in short, anthropomorphize it, or reduce it to some such character as that borne by the ordinary proceedings of mankind. And yet this would be unavoidable; for that the organic creation was thus progressive through a long space of time, rests on evidence which nothing can overturn or gainsay.

Some other idea must then be come to with regard to the mode in which the Divine Author proceeded in the organic creation. Let us seek in the history of the earth's formation for a new suggestion on this point.

...organic creation is ... a result of natural laws...

We have seen powerful evidence, that the construction of this globe and its associates, and inferentially that of all the other globes of space, was the result, not of any immediate or personal exertion on the part of the Deity, but of natural laws which are expressions of his will. What is to hinder our supposing that the organic creation is also a result of natural laws, which are in like manner an expression of his will? More than this, the fact of the cosmical arrangements being an effect of natural law, is a powerful argument for the organic arrangements being so likewise, for how can we suppose that the august Being who brought all these countless worlds into form by the simple establishment of a natural principle flowing from his mind, was to interfere personally and specially on every occasion when a new shell-fish or reptile was to be ushered into existence on one of these worlds? Surely this idea is too ridiculous to be for a moment entertained....

To a reasonable mind the Divine attributes must appear, not diminished or reduced in any way, by supposing a creation by law, but infinitely exalted. It is the narrowest of all views of the Deity, and characteristic of a humble class of intellects, to suppose him acting constantly in particular ways for particular occasions. It, for one thing, greatly detracts from his foresight, the most undeniable of all the attributes of Omnipotence. It lowers him towards the level of our own humble intellects. Much more worthy of him it surely is, to suppose that all things have been commissioned by him from the first, though neither is he absent from a particle of the current of natural affairs in one sense, seeing that the whole system is continually supported by his providence....

Those who would object to the hypothesis of a creation by the intervention of law, do not perhaps consider how powerful an argument in favour of the existence of God is lost by rejecting this doctrine. When all is seen to be the result of law, the idea of an Almighty Author becomes irresistible, for the creation of a law for an endless series of phenomena--an act of intelligence above all else that we can conceive--could have no other imaginable source, and tells, moreover, as powerfully for a sustaining as for an originating power....

...That harmony ... which generally marks great truths...

It may here be remarked that there is in our doctrine that harmony in all the associated phenomena which generally marks great truths. First, it agrees, as we have seen, with the idea of planet-creation by natural law. Secondly, upon this supposition, all that geology tells us of the succession of species appears natural and intelligible. Organic life presses in, as has been remarked, wherever there was room and encouragement for it, the forms being always such as suited the circumstances, and in a certain relation to them....

Admitting for a moment a re-origination of species after a cataclysm, as has been surmised by some geologists, though the hypothesis is always becoming less and less tenable, it harmonizes with nothing so well as the idea of a creation by law. The more solitary commencements of species, which would have been the most inconceivably paltry exercise for an immediately creative power, are sufficiently worthy of one operating by laws.

It is also to be observed, that the thing to be accounted for is not merely the origination of organic being upon this little planet ... which is but one of hundreds of thousands.... We have to suppose, that every one of these numberless globes is either a theatre of organic being, or in the way of becoming so....

Is it conceivable, as a fitting mode of exercise for creative intelligence, that it should be constantly moving from one sphere to another, to form and plant the various species which may be required in each situation at particular times? Is such an idea accordant with our general conception of the dignity, not to speak of the power, of the Great Author? Yet such is the notion which we must form, if we adhere to the doctrine of special exercise. Let us see, on the other hand, how the doctrine of a creation by law agrees with this expanded view of the organic world....

...the doctrine of creation by law...

Suppose that the first persons of an early nation who made a ship and ventured to sea in it, observed, as they sailed along, a set of objects which they had never before seen--namely, a fleet of other ships--would they not have been justified in supposing that those ships were occupied, like their own, by human beings possessing hands to row and steer, eyes to watch the signs of the weather, intelligence to guide them from one place to another--in short, beings in all respects like themselves, or only shewing such differences as they knew to be producible by difference of climate and habits of life.

Precisely in this manner we can speculate on the inhabitants of remote spheres. We see that matter has originally been diffused in one mass, of which the spheres are portions. Consequently, inorganic matter must be presumed to be everywhere the same, although probably with differences in the proportions of ingredients in different globes, and also some difference of conditions. Out of a certain number of the elements of inorganic matter are composed organic bodies, both vegetable and animal; such must be the rule in Jupiter and in Sirius, as it is here....

Gravitation we see to be an all-pervading principle: therefore there must be a relation between the spheres and their respective organic occupants, by virtue of which they are fixed, as far as necessary, on the surface. Such a relation, of course, involves details as to the density and elasticity of structure, as well as size, of the organic tenants, in proportion to the gravity of the respective planets....

Electricity we also see to be universal; if, therefore, it be a principle concerned in life and in mental action, as science strongly suggests, life and mental action must everywhere be of one general character.

We come to comparatively a matter of detail, when we advert to heat and light; yet it is important to consider that these are universal agents, and that, as they bear marked relations to organic life and structure on earth, they may be presumed to do so in other spheres also.

The considerations as to light are particularly interesting, for, on our globe, the structure of one important organ, almost universally distributed in the animal kingdom, is in direct and precise relation to it. Where there is light there will be eyes, and these, in other spheres, will be the same in all respects as the eyes of tellurian animals, with only such differences as may be necessary to accord with minor peculiarities of condition and of situation.

...a small stretch...

It is but a small stretch of the argument to suppose that, one conspicuous organ of a large portion of our animal kingdom being thus universal, a parity in all the other organs--species for species, class for class, kingdom for kingdom--is highly likely, and that thus the inhabitants of all the other globes of space bear not only a general, but a particular resemblance to those of our own.

Assuming that organic beings are thus spread over all space, the idea of their having all come into existence by the operation of laws everywhere applicable, is only conformable to that principle, acknowledged to be so generally visible in the affairs of Providence, to have all done by the employment of the smallest possible amount of means. Thus, as one set of laws produced all orbs and their motions and geognostic arrangements, so one set of laws overspread them all with life. The whole productive or creative arrangements are therefore in perfect unity.

CHAPTER 13

PARTICULAR CONSIDERATIONS RESPECTING THE ORIGIN OF THE ANIMATED

TRIBES.

[Supporting facts]

THE general likelihood of an organic creation by law having been shewn, we are next to inquire if science has any facts tending to bring the assumption more nearly home to nature. Such facts there certainly are; but it cannot be surprising that they are comparatively few and scattered, when we consider that the inquiry is into one of nature's profoundest mysteries, and one which has hitherto engaged no direct attention in almost any quarter.

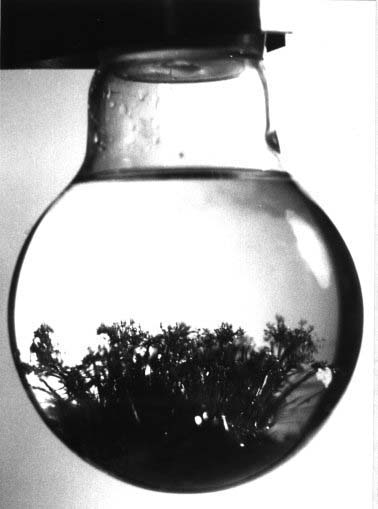

Crystallization is confessedly a phenomenon of inorganic matter; yet the simplest rustic observer is struck by the resemblance which the examples of it left upon a window by frost bear to vegetable forms. In some crystallizations the mimicry is beautiful and complete; for example, in the well-known one called the Arbor Dianæ [Tree of Diana].

An amalgam of four parts of silver and two of mercury being dissolved

in nitric acid, and water equal to thirty weights of the metals being added,

a small piece of soft amalgam of silver suspended in the solution, quickly

gathers to itself the particles of the silver of the amalgam, which form

upon it a crystallization precisely resembling a shrub....

Arbor Dianæ

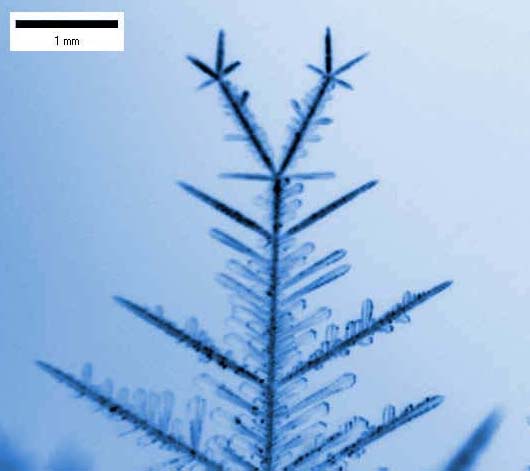

Vegetable figures are also presented in some of the most ordinary appearances of the electric fluid. In the marks caused by positive electricity, or which it leaves in its passage, we see the ramifications of a tree, as well as of its individual leaves; those of the negative, recall the bulbous or the spreading root, according as they are clumped or divergent.

These phenomena seem to say that the electric energies have had something

to do in determining the forms of plants. That they are intimately

connected with vegetable life is indubitable, for germination will not

proceed in water charged with negative electricity, while water charged

positively greatly favours it; and a garden sensibly increases in luxuriance,

when a number of conducting rods are made to terminate in branches over

its beds. With regard to the resemblance of the ramifications of

the branches and leaves of plants to the traces of the positive electricity,

and that of the roots to the negative, it is a circumstance calling for

especial remark, that the atmosphere, particularly its lower strata, is

generally charged positively, while the earth is always charged negatively.

The correspondence here is curious. A plant thus appears as a thing

formed on the basis of a natural electrical operation....

Snow crystal grown in an electric field. When the applied voltage crossed a certain threshold, the tip of the crystal split and began growing symmetrically in two divergent directions.

[B]ut it will be asked what actual experience says respecting the origination of life. Are there, it will be said, any authentic instances of either plants or animals, of however humble and simple a kind, having come into existence otherwise than in the ordinary way of generation, since the time of which geology forms the record? It may be answered, that the negative of this question could not be by any means formidable to the doctrine of law--creation, seeing that the conditions necessary for the operation of the supposed life--creating laws may not have existed within record to any great extent. On the other hand, as we see the physical laws of early times still acting with more or less force, it might not be unreasonable to expect that we should still see some remnants, or partial and occasional workings of the life-creating energy amidst a system of things generally stable and at rest. Are there, then, any such remnants to be traced in our own day, or during man's existence upon earth? If there be, it clearly would form a strong evidence in favour of the doctrine, as what now takes place upon a confined scale and in a comparatively casual manner may have formerly taken place on a great scale, and as the proper and eternity-destined means of supplying a vacant globe with suitable tenants. It will at the same time be observed that, the earth being now supplied with both kinds of tenants in great abundance, we only could expect to find the life-originating power at work in some very special and extraordinary circumstances, and probably only in the inferior and obscurer departments of the vegetable and animal kingdoms....

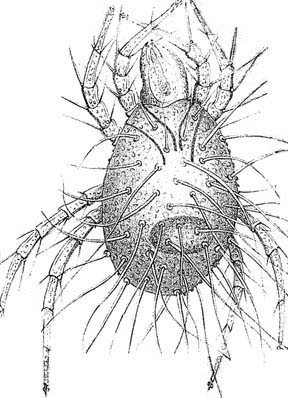

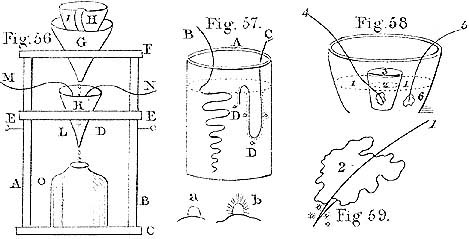

[E]xperiments conducted a few years ago by Mr. [Andrew] Crosse ... seemed

to result in the production of a heretofore unknown species of insect in

considerable numbers. Various causes have prevented these experiments

and their results from receiving candid treatment, but they may perhaps

be yet found to have opened up a new and most interesting chapter of nature's

mysteries. Mr. Crosse was pursuing some experiments in crystallization,

causing a powerful voltaic battery to operate upon a saturated solution

of silicate of potash, when the insects unexpectedly made their appearance.

He afterwards tried nitrate of copper, which is a deadly poison, and from

that fluid also did live insects emerge.

| [W]e submitted [the acarus of Mr. Crosse]

to the action of the microscope, which magnified about 280 times.

By this mode of observation we perceived that the body was of an oval form, the belly slightly flattened, and the back very round, particularly towards the hind end of the body. The skin of the back appeared chagrined, or as strewed with an infinite number of very small tubercles, of which a certain number, larger than the others, distributed here and there, serve as a base or bulb for long hairs or silks, which are at least as long as the body of the animal. All these hairs fixed and raised on the protuberant back of this kind of acarus, give it the appearance of a microscopic porcupine, to which the elongated snout also contributes. --Annals of Electricity, Magnetism & Chemistry, Vol. 2: 355-360 (January-June 1838) |

|

Discouraged by the reception of his experiments, Mr. Crosse soon discontinued them; but they were some years after pursued by Mr. [William Henry] Weekes, of Sandwich, with precisely the same results. This gentleman, besides trying the first of the above substances, employed ferro-cyanet of potash, on account of its containing a larger proportion of carbon, the principal element of organic bodies; and from this substance the insects were produced in increased numbers. A few weeks sufficed for this experiment, with the powerful battery of Mr. Crosse; but the first attempts of Mr. Weekes required about eleven months, a ground of presumption in itself that the electricity was chiefly concerned in the phenomenon. The changes undergone by the fluid operated upon, were in both cases remarkable, and nearly alike.

In Mr. Weekes' apparatus, the silicate of potash became first turbid,

then of a milky appearance; round the negative wire of the battery, dipped

into the fluid, there gathered a quantity of gelatinous matter, a part

of the process of considerable importance, considering that gelatin is

one of the proximate principles, or first compounds, of which animal bodies

are formed. From this matter Mr. Weekes observed one of the insects

in the very act of emerging, immediately after which, it ascended to the

surface of the fluid, and sought concealment in an obscure corner of the

apparatus. The insects produced by both experimentalists seem to

have been the same, a species of acarus, minute and semi-transparent, and

furnished with long bristles, which can only be seen by the aid of the

microscope. It is worthy of remark, that some of these insects, soon

after their existence had commenced, were found to be likely to extend

their species. They were sometimes observed to go back to the fluid

to feed, and occasionally they devoured each other.

Apparatus in which Crosse's acari first made their appearance.

The reception of novelties in science must ever be regulated very much by the amount of kindred or relative phenomena which the public mind already possesses and acknowledges, to which the new can be assimilated. A novelty, however true, if there be no received truths with which it can be shewn in harmonious relation, has little chance of a favourable hearing....

The experiments above described, finding a public mind which had never discovered a fact or conceived an idea at all analogous, were of course ungraciously received. It was held to be impious, even to surmise that animals could have been formed through any instrumentality of an apparatus devised by human skill. The more likely account of the phenomena was said to be, that the insects were only developed from ova, resting either in the fluid, or in the wooden frame on which the experiments took place.

On these objections the following remarks may be made. The supposition of impiety arises from an entire misconception of what is implied by an aboriginal creation of insects. The experimentalist could never be considered as the author of the existence of these creatures, except by the most unreasoning ignorance. The utmost that can be claimed for, or imputed to him is that he arranged the natural conditions under which the true creative energy--that of the Divine Author of all things--has pleased to work in that instance.

On the hypothesis here brought forward, the acarus Crossii was a type of being ordained from the beginning, and destined to be realized under certain physical conditions. When a human hand brought these conditions into the proper arrangement, it did an act akin to hundreds of familiar ones which we execute every day, and which are followed by natural results; but it did nothing more. The production of the insect, if it did take place as assumed, was as clearly an act of the Almighty himself, as if he had fashioned it with hands. For the presumption that an act of aboriginal creation did take place, there is this to be said, that, in Mr. Weekes's experiment, every care that ingenuity could devise was taken to exclude the possibility of a development of the insects from ova. The wood of the frame was baked in a powerful heat; a bell-shaped glass covered the apparatus, and from this the atmosphere was excluded by the constantly rising fumes from the liquid, for the emission of which there was an aperture so arranged at the top of the glass, that only these fumes could pass. The water was distilled, and the substance of the silicate had been subjected to white heat. Thus every source of fallacy seemed to be shut up. In such circumstances, a candid mind, which sees nothing either impious or unphilosophical in the idea of a new creation, will be disposed to think that there is less difficulty in believing in such a creation having actually taken place, than in believing that, in two instances, separated in place and time, exactly the same insects should have chanced to arise from concealed ova, and these a species heretofore unknown....

CHAPTER 14

HYPOTHESIS OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE

VEGETABLE AND ANIMAL KINGDOMS.

IT has been already intimated, as a general fact, that there is an obvious gradation amongst the families of both the vegetable and animal kingdoms, from the simple lichen and animalcule respectively up to the highest order of dicotyledonous trees and the mammalia. Confining our attention, in the meantime, to the animal kingdom--it does not appear that this gradation passes along one line, on which every form of animal life can be, as it were, strung; there may be branching or double lines at some places; or the whole may be in a circle composed of minor circles, as has been recently suggested. But still it is incontestable that there are general appearances of a scale beginning with the simple and advancing to the complicated....

[The] facts clearly shew how all the various organic forms of our world are bound up in one--how a fundamental unity pervades and embraces them all, collecting them, from the humblest lichen up to the highest mammifer, in one system, the whole creation of which must have depended upon one law or decree of the Almighty, though it did not all come forth at one time....

It is only in recent times that physiologists have observed that each animal passes, in the course of its germinal history, through a series of changes resembling the permanent forms of the various orders of animals inferior to it in the scale.... Nor is man himself exempt from this law. His first form is that which is permanent in the animalcule. His organization gradually passes through conditions generally resembling a fish, a reptile, a bird, and the lower mammalia, before it attains its specific maturity. At one of the last stages of his foetal career, he exhibits an intermaxillary bone, which is characteristic of the perfect ape; this is suppressed, and he may then be said to take leave of the simial type, and become a true human creature....

The whole train of animated beings, from the simplest and oldest up to the highest and most recent, are, then, to be regarded as a series of advances of the principle of development, which have depended upon external physical circumstances, to which the resulting animals are appropriate....

It has been seen that, in the reproduction of the higher animals, the new being passes through stages in which it is successively fish-like and reptile-like. But the resemblance is not to the adult fish or the adult reptile, but to the fish and reptile at a certain point in their foetal progress; this holds true with regard to the vascular, nervous, and other systems alike....

The idea, then, which I form of the progress of organic life upon the globe--and the hypothesis is applicable to all similar theatres of vital being--is, that the simplest and most primitive type, under a law to which that of like-production is subordinate, gave birth to the type next above it, that this again produced the next higher, and so on to the very highest, the stages of advance being in all cases very small--namely, from one species only to another; so that the phenomenon has always been of a simple and modest character. Whether the whole of any species was at once translated forward, or only a few parents were employed to give birth to the new type, must remain undetermined; but, supposing that the former was the case, we must presume that the moves along the line or lines were simultaneous, so that the place vacated by one species was immediately taken by the next in succession, and so on back to the first, for the supply of which the foundation of a new germinal vesicle out of inorganic matter was alone necessary. Thus, the production of new forms, as shewn in the pages of the geological record, has never been anything more than a new stage of progress in gestation, an event as simply natural, and attended as little by any circumstances of a wonderful or startling kind, as the silent advance of an ordinary mother from one week to another of her pregnancy....

Early in this century, M. Lamarck, a naturalist of the highest character, suggested an hypothesis of organic progress which deservedly incurred much ridicule, although it contained a glimmer of the truth. He surmised, and endeavoured, with a great deal of ingenuity, to prove, that one being advanced in the course of generations to another, in consequence merely of its experience of wants calling for the exercise of its faculties in a particular direction, by which exercise new developments of organs took place, ending in variations sufficient to constitute a new species. Thus he thought that a bird would be driven by necessity to seek its food in the water, and that, in its efforts to swim, the outstretching of its claws would lead to the expansion of the intermediate membranes, and it would thus become web-footed.

Now it is possible that wants and the exercise of faculties have entered in some manner into the production of the phenomena which we have been considering; but certainly not in the way suggested by Lamarck, whose whole notion is obviously so inadequate to account for the rise of the organic kingdoms, that we only can place it with pity among the follies of the wise. Had the laws of organic development been known in his time, his theory might have been of a more imposing kind. It is upon these that the present hypothesis is mainly founded. I take existing natural means, and shew them to have been capable of producing all the existing organisms, with the simple and easily conceivable aid of a higher generative law, which we perhaps still see operating upon a limited scale. I also go beyond the French philosopher to a very important point, the original Divine conception of all the forms of being which these natural laws were only instruments in working out and realizing....

[R]egularity in the structure, as we may call it, of the classification of animals, as is shewn in their systems, is totally irreconcilable with the idea of form going on to form merely as needs and wishes in the animals themselves dictated. Had such been the case, all would have been irregular, as things arbitrary necessarily are. But, lo, the whole plan of being is as symmetrical as the plan of a house, or the laying out of an old-fashioned garden! This must needs have been devised and arranged for beforehand....

Let us only for a moment consider how various are the external physical conditions in which animals live--climate, soil, temperature, land, water, air--the peculiarities of food, and the various ways in which it is to be sought; the peculiar circumstances in which the business of reproduction and the care-taking of the young are to be attended to--all these required to be taken into account, and thousands of animals were to be formed suitable in organization and mental character for the concerns they were to have with these various conditions and circumstances--here a tooth fitted for crushing nuts; there a claw fitted to serve as a hook for suspension; here to repress teeth and develop a bony net-work instead; there to arrange for a bronchial apparatus, to last only for a certain brief time; and all these animals were to be schemed out, each as a part of a great range, which was on the whole to be rigidly regular: let us, I say, only consider these things, and we shall see that the decreeing of laws to bring the whole about was an act involving such a degree of wisdom and device as we only can attribute, adoringly, to the one Eternal and Unchangeable....

CHAPTER 16

EARLY HISTORY OF MANKIND.

[T]here is ... a remarkable persistency in national features and forms, insomuch that a single individual thrown into a family different from himself is absorbed in it, and all trace of him lost after a few generations. But while there is such a persistency to ordinary observation, it would also appear that nature has a power of producing new varieties, though this is only done rarely. Such novelties of type abound in the vegetable world, are seen more rarely in the animal circle, and perhaps are least frequent of occurrence in our own race. There is a noted instance in the production, on a New England farm, of a variety of sheep with unusually short legs, which was kept up by breeding, on account of the convenience in that country of having sheep which are unable to jump over low fences. The starting and maintaining of a breed of cattle, that is, a variety marked by some desirable peculiarity, are familiar to a large class of persons. It appears only necessary, when a variety has been thus produced, that a union should take place between individuals similarly characterized, in order to establish it.

Early in the last century, a man named Lambert, was born in Suffolk, with semi-horny excrescences of about half an inch long, thickly growing all over his body. The peculiarity was transmitted to his children, and was last heard of in a third generation. The peculiarity of six fingers on the hand and six toes on the feet, appears in like manner in families which have no record or tradition of such a peculiarity having affected them at any former period, and it is then sometimes seen to descend through several generations. It was Mr. Lawrence's opinion, that a pair, in which both parties were so distinguished, might be the progenitors of a new variety of the race who would be thus marked in all future time.

It is not easy to surmise the causes which operate in producing such varieties. Perhaps they are simply types in nature, possible to be realized under certain appropriate conditions, but which conditions are such as altogether to elude notice.... We are ignorant of the laws of variety-production; but we see it going on as a principle in nature, and it is obviously favourable to the supposition that all the great families of men are of one stock....

[T]here may have been different lines and sources of origination, geographically apart, but which all resulted uniformly in the production of a being, one in species, although variously marked....

Civilization

To have civilization, it is necessary that a people should be numerous and closely placed; that they should be fixed in their habitations, and safe from violent external and internal disturbance; that a considerable number of them should be exempt from the necessity of drudging for immediate subsistence.... [H]ence it will be found that all civilizations as yet known have taken place in regions physically limited. That of Egypt arose in a narrow valley hemmed in by deserts on both sides. That of Greece took its rise in a small peninsula bounded on the only land side by mountains. Etruria and Rome were naturally limited regions....

The United States might be expected to make no great way in civilization till they be fully peopled to the Pacific; and it might not be unreasonable to expect that, when that even has occurred, the greatest civilizations of that vast territory will be found in the peninsula of California and the narrow stripe of country beyond the Rocky Mountains....

CHAPTER 18

PURPOSE AND GENERAL CONDITION OF THE ANIMATED CREATION.

....The system of nature assures us that benevolence is a leading principle in the divine mind. But that system is at the same time deficient in a means of making this benevolence of invariable operation. To reconcile this to the recognised character of the Deity, it is necessary to suppose that the present system is but a part of a whole, a stage in a Great Progress, and that the Redress is in reserve....

[T]he economy of nature, beautifully arranged and vast in its extent as it is, does not satisfy even man's idea of what might be; he feels that, if this multiplicity of theatres for the exemplification of such phenomena as we see on earth were to go on for ever unchanged, it would not be worthy of the Being capable of creating it. An endless monotony of human generations, with their humble thinkings and doings, seems an object beneath that august Being. But the mundane economy might be very well as a portion of some greater phenomenon, the rest of which was yet to be evolved.

It therefore appears that our system, though it may at first appear at issue with other doctrines in esteem amongst mankind, tends to come into harmony with them, and even to give them support. I would say, in conclusion, that, even where the two above arguments may fail of effect, there may yet be a faith derived from this view of nature sufficient to sustain us under all sense of the imperfect happiness, the calamities, the woes, and pains of this sphere of being. For let us but fully and truly consider what a system is here laid open to view, and we cannot well doubt that we are in the hands of One who is both able and willing to do us the most entire justice. And in this faith we may well rest at ease, even though life should have been to us but a protracted disease, or though every hope we had built on the secular materials within our reach were felt to be melting from our grasp. Thinking of all the contingencies of this world as to be in time melted into or lost in the greater system, to which the present is only subsidiary, let us wait the end with patience, and be of good cheer.

NOTE CONCLUSORY.

THUS ends a book, composed in solitude, and almost without the cognizance of a single human being, for the sole purpose (or as nearly so as may be) of improving the knowledge of mankind, and through that medium their happiness. For reasons which need not be specified, the author's name is retained in its original obscurity, and, in all probability, will never be generally known. I do not expect that any word of praise which the work may elicit shall ever be responded to by me, or that any word of censure shall ever be parried or deprecated. It goes forth to take its chance of instant oblivion, or of a long and active course of usefulness in the world. Neither contingency, can be of any importance to me, beyond the regret or the satisfaction which may be imparted by my sense of a lost or a realized benefit to my fellow-creatures.

The book, as far as I am aware, is the first attempt to connect the natural sciences into a history of creation. The idea is a bold one, and there are many circumstances of time and place to render its boldness more than usually conspicuous. But I believe my doctrines to be in the main true; I believe all truth to be valuable, and its dissemination a blessing. At the same time, I hold myself duly sensible of the common liability to error, but am certain that no error in this line has the least chance of being allowed to injure the public mind. Therefore I publish. My views, if correct, will most assuredly stand, and may sooner or later prove beneficial; if otherwise, they will as surely pass out of notice without doing any harm.

My sincere desire in the composition of the book was to give the true view of the history of nature, with as little disturbance as possible to existing beliefs, whether philosophical or religious. I have made little reference to any doctrines of the latter kind which may be thought inconsistent with mine, because to do so would have been to enter upon questions for the settlement of which our knowledge is not yet ripe. Let the reconciliation of whatever is true in my views with whatever is true in other systems come about in the fulness of calm and careful inquiry.

I cannot but here remind the reader of what Dr. Wiseman has shewn so strikingly in his lectures, how different new philosophic doctrines are apt to appear after we have become somewhat familiar with them. Geology at first seems inconsistent with the authority of the Mosaic record. A storm of un-reasoning indignation rises against its teachers. In time, its truths, being found quite irresistible, are admitted, and mankind continue to regard the Scriptures with the same respect as before. So also with several other sciences.

Now the only objection that can be made on such ground to this book, is, that it brings forward some new hypotheses, at first sight, like geology, not in perfect harmony with that record, and arranges all the rest into a system which partakes of the same character. But may not the sacred text, on a liberal interpretation, or with the benefit of new light reflected from nature, or derived from learning, be shewn to be as much in harmony with the novelties of this volume as it has been with geology and natural philosophy? What is there in the laws of organic creation more startling to the candid theologian than in the Copernican system or the natural formation of strata? And if the whole series of facts is true, why should we shrink from inferences legitimately flowing from it? Is it not a wiser course, since reconciliation has come in so many instances, still to hope for it, still to go on with our new truths, trusting that they also will in time be found harmonious with all others? Thus we avoid the damage which the very appearance of an opposition to natural truth is calculated to inflict on any system presumed to require such support. Thus we give, as is meet, a respectful reception to what is revealed through the medium of nature, at the same time that we fully reserve our reverence for all we have been accustomed to hold sacred, not one tittle of which it may ultimately be found necessary to alter.

|