University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Week 3. Humanism Preface to the Reader

|

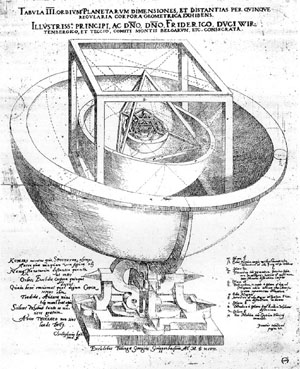

It is my intention, reader, to show in this little book that the most great and good Creator, in the creation of this moving universe, and the arrangement of the heavens, looked to those five regular solids, which have been so celebrated from the time of Pythagoras and Plato down to our own, and that he fitted to the nature of those solids, the number of the heavens, their proportions, and the law of their motions. But before permitting you to come to the actual subject, I shall discuss briefly both what occasioned this book and my reason for undertaking it, which I think will affect not only your understanding but my reputation.

Six years ago, when I was studying under the distinguished Master Michael Maestlin at Tübingen, I was disturbed by the many difficulties of the usual conception of the universe, and I was so delighted by Copernicus ... that I not only frequently defended his opinions at the disputations of candidates in physics but even wrote out a thorough disputation on the first motion [the earth's revolution around the sun] ... but where Copernicus did so through mathematical arguments, mine were physical, or rather metaphysical....

There were three things in particular about which I persistently sought the reasons why they were such and not otherwise: the number, the size, and the motion of the circles.... In the beginning I attacked the business by numbers, and considered whether one circle was twice another, or three times, or four times, or whatever, and how far any one was separated from another according to Copernicus. I wasted a great deal of time on that toil, as if at a game, since no agreement appeared either in the proportions themselves or in the differences; and I derived nothing of value from that except that I engraved deeply on my memory the distances which were published by Copernicus.... If (thought I) God allotted motions to the spheres to correspond with their distances, similarly he made the distances themselves correspond with something.

Since, then, this method was not a success, I tried an approach by another way, of remarkable boldness. Between Jupiter and Mars I placed a new planet, and also another between Venus and Mercury, which were to be invisible perhaps on account of their tiny size, and I assigned periodic times to them. For I thought that in this way I should produce some agreement between the ratios.... Yet the interposition of a single planet was not sufficient for the huge gap between Jupiter and Mars; for the ratio of Jupiter to the new planet remained greater than that of Saturn to Jupiter.... And I could not conjecture from the nobility of any number why so few moving stars [planets] existed in proportion to the infinite number (of the fixed stars).

Again I investigated by [yet] another method.... [which Kepler goes on to describe in agonizing detail]

Almost a whole summer was wasted on this ordeal. Eventually by a certain mere accident I chanced to come closer to the actual state of affairs. I thought it was by divine intervention that I gained fortuitously what I was never able to obtain by any amount of toil; and I believed that all the more because I had always prayed to God that if Copernicus had told the truth things should proceed in this way. [Kepler goes on to describe his idea of inscribing and circumscribing circles about a set of regular polygons thus generating a series of nesting circles whose sizes are constrained by the numbers of sides of each polygon. He abandons this when he realizes there is no natural limit on the number of possible polygons while there is a limit to the number of planets observed.]

The end of this useless attempt was also the beginning of the last, and successful one. I naturally concluded that by this method if I wished to keep an order among the figures, I should never reach the Sun, nor have an explanation why there should be six moving circles rather than twenty or a hundred. However, the figures were satisfactory, as they represented quantities, and so something prior to the heavens. For quantity was created in the beginning along with matter, but the heavens on the second day.

|

But if (thought I) corresponding with the size and proportion of the six heavens, as Copernicus established them, there could be found only five figures, among the infinite number of others, which had certain special properties distinct from the rest, it would be the answer to my prayer. Again I set to. Why should there be plane figures between solid spheres? It would be more appropriate to try solid bodies. Behold, reader, this is my discovery and the subject matter of the whole of this little work. For if anyone having a slight acquaintance with geometry were informed of this in so many words, there would immediately come to his mind the five regular solids with the proportion of their circumscribed spheres to those inscribed....

This accident was also the happy ending of my toil. You can now also see my scheme for this book. What delight I have found in this discovery I shall never be able to express in words. No longer did I regret the wasted time; I was no longer sick of the toil; I did not avoid any of the tedium of the calculation; I devoted my days and nights to computation, until such time as I could see whether the proposition which I had conceived in words would agree with the circles of Copernicus, or whether my joy would be scattered to the winds. But if I found out that I was right, I made a vow to Almighty God that at the first opportunity I would proclaim among men in public print this wonderful example of his wisdom....

|