Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

![]()

Week 5. The Age of Enlightenment.

excerpts from

Conversations on the Plurality of Worlds

(1686)

by Bernard le Bovier de Fontenelle (1657-1757)

![]()

| If it turns out that this book is read, I warn those who have some

knowledge of Physics that I don't pretend at all to instruct them but only

to divert them, by presenting to them, in a little more agreeable and engaging

manner, that which they already know solidly. I inform those to whom

these matters are new that I believe I can instruct and divert them all

at the same time. The first group will thwart my intention if they

seek profit here, and the second if they seek only pleasure.

I do not delude myself when I say that I've chosen from all of Philosophy the subject most apt to pique curiosity. It seems to me that nothing could be of greater interest to us than to know how this world we inhabit is made, if there are other worlds which are similar to it, and like it are inhabited too; but after all, let those who wish trouble themselves about all that; I'm certain no one would trouble himself just to please me by reading my book. Those who have thoughts to waste can waste them on such things; not everyone can afford such unprofitable expense. I've placed a woman in these Conversations who is being instructed, one who has never heard a syllable about such things. I thought this fiction would serve to make the work more enticing, and to encourage women through the example of a woman who, having nothing of an extraordinary character, without ever exceeding the limitations of a person who has no knowledge of science, never fails to understand what's said to her, and arranges in her mind, without confusion, vortices, and worlds. Why would any woman accept inferiority to this imaginary Marquise, who only conceives of those things of which she can't help but conceive?.... Since I had no intention of creating a make-believe system, without any foundation, I've employed verifiable physical tenets, as many as were necessary. But fortunately it happens that on this subject the ideas of physics are pleasing in themselves and, at the same time that they're satisfying the mind, they provide a spectacle for the imagination which pleases it as much as if they had been made expressly for that purpose.... I did not wish to make up anything about inhabitants of worlds which would be totally fantastic. I've tried to say everything one might reasonably think about them, and even the imaginings I've added to this have some foundation in reality. The true and the false are mixed here, but they are always easy to distinguish. I make no attempt to justify so bizarre a mixture; it is the single most important point of the work, and it is precisely the one for which I cannot supply a reason.... [To] the scrupulous people who will think there is danger in respect to religion in placing inhabitants elsewhere than on Earth: I respect even the most excessive sensibilities people have on the matter of religion, and I would have respected religion itself to the point of wishing not to offend it in a public work, even if it were contrary to my own opinion. But what may be surprising to you is that religion simply has nothing to do with this system, in which I fill an infinity of worlds with inhabitants. It's only necessary to sort out a little error of the imagination. When I say to you that the Moon is inhabited, you picture to yourself men made like us, and then, if you're a bit of a theologian, you're instantly full of qualms. The descendants of Adam have not spread to the Moon, nor sent colonies there. Therefore the men in the Moon are not sons of Adam. Well, it would be embarrassing to Theology if there were men anywhere not descended from him. It's not necessary to say any more about it; all imaginable difficulties boil down to that, and the terms that must be employed in any longer explication are too serious and dignified to be placed in a book as unserious as this. Perhaps I could respond soundly enough if I undertook it, but certainly I have no need to respond. It rests entirely upon the men on the Moon, but it's you who are putting those men on the Moon. I put no men there at all: I put inhabitants there who are not like men in any way. What are they, then? I've never seen them. It's not because I've seen them that I talk of them, and don't think that's a loophole through which I can elude your objection, simply saying that there are no men on the Moon. You'll see it's impossible that any could be there, according to my idea of the infinite diversity that Nature has placed in her works. This idea governs the whole book, and cannot be contested by any philosopher. Therefore, I believe that I'll only hear people object who talk of these Conversations without having read them. But is this any reason for me to be reassured? No, on the contrary, it's a very legitimate reason for fearing that the objection will be raised in many places. |

The First Evening |

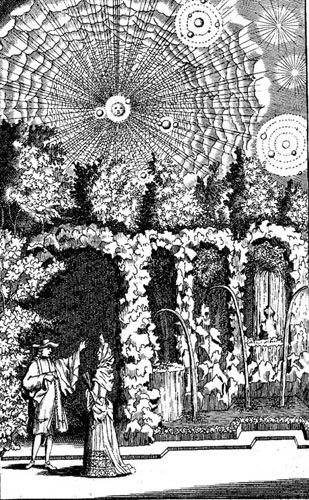

One evening after supper we went to walk in the garden. There was a delicious breeze, which made up for the extremely hot day we had had to bear. The Moon had risen about an hour before, and shining through the trees it made a pleasant mixture of bright white against the dark greenery that appeared black. There was no cloud to hide even the smallest star; they were all pure and shining gold and stood out clearly against their blue background. The spectacle set me to musing, and I might have gone on like that for some time if it had not been for the Marquise, but in the company of such a lovely woman I could hardly give myself up to the Moon and stars.... "I love the stars, [she said] and I'm almost angry with the Sun for overpowering them." "I can never forgive it," I cried, "for making me lose sight of all those worlds." "What do you mean, worlds?" she asked, turning to me.... "I'm ashamed to admit it," I said, "but I have a peculiar notion that every star could well be a world. I wouldn't swear that it's true, but I think so because it pleases me to think so. The idea sticks in my mind in a most delightful way. As I see it, this pleasure is an integral part of truth itself." "Well," said the Marquise, "if your idea is so pleasing, share it with me. I'll believe that the stars are anything you say, if I enjoy it." "Ah, Madame," I answered, "this isn't enjoyment such as you'd find in a Molière comedy; it's enjoyment that involves our reasoning powers. It only delights the mind." "What?" she cried. "Do you think I'm incapable of enjoying intellectual pleasures? I'll show you otherwise right now. Tell me about your stars!"... To someone like the Marquise, who knew nothing of Natural Philosophy, I would have to go a long way to prove that the Earth might be a planet, the other planets Earths, and all the stars solar systems.... "All philosophy," I told her, "is based on two things only: curiosity and poor eyesight; if you had better eyesight you could see perfectly well whether or not these stars are solar systems, and if you were less curious you wouldn't care about knowing, which amounts to the same thing, but we see things other than as they are. So true philosophers spend a lifetime not believing what they do see, and theorizing on what they don't see, and it's not, to my way of thinking, a very enviable situation...." |

"Well then," I said to her, "now that the Sun, which is presently motionless, has ceased to be a planet, and the Earth which rolls around him has begun to be one, you won't be surprised to hear that the Moon is a world like the Earth, and that apparently she's inhabited." But I've never yet heard anyone say that the Moon was inhabited," she replied, "except as a fantasy and a delusion." "This may be a fantasy too," I answered. "I don't take sides in these matters except as one does in civil wars, when the uncertainty of what might happen makes one maintain contacts on the opposite side, and make arrangements even with the enemy. As for me, although I see the Moon as inhabited, I still live on good terms with those who don't believe it, and I keep myself in a position where I could shift to their opinion honorably if they gained the upper hand. but while we wait for them to have some considerable advantage over us, here is what has made me take the side of an inhabited Moon. "Let's suppose that there has never been any communication between Paris and Saint-Denis, and that a townsman of Paris, who has never been out of his city, is in the towers of Notre Dame and sees Saint-Denis in the distance. Ask him if he believes Saint-Denis is inhabited; he'll deny it heartily, saying 'I can see the people of Paris quite well, but I don't see the people of Saint-Denis at all, and I've never heard tell of them.' "Someone will point out to him that of course when one is in the towers of Notre Dame one doesn't see the people of Saint-Denis, but that's because of the great distance. Everything one can see of Saint-Denis strongly resembles Paris, however; Saint-Denis has steeples, houses, walls, and it might resemble Paris in that it's inhabited as well. All this will make no impression on my townsman; he will obstinately maintain forever that Saint-Denis is uninhabited because he has seen nobody there. Our Saint-Denis is the Moon, and each of us is a Parisian who has never gone outside his city." "Ah," the Marquise interrupted, "you wrong us. We aren't all so stupid as your townsman; since he sees that Saint-Denis is made exactly like Paris, he'd be out of his mind not to believe it's inhabited; but the Moon isn't made at all like the Earth." "Be careful, Madame," I replied, "for if what we need is that the Moon should completely resemble the Earth, you'll find yourself obliged to believe the Moon inhabited." "I confess," she answered, "that there would be no way to get out of it, and I see you've an air of confidence that frightens me already. The two motions of the Earth, which I had never suspected, make me timid concerning all the rest. And yet, can it be possible that the Earth shines the way the Moon does? It must, if they are to resemble one another." "Alas, Madam," I replied, "to be luminous isn't such a great thing as you think. Only in the Sun is this a remarkable quality. It shines all by itself because of its particular nature, but the planets only light up because they're lit by the Sun. He sends his light to the Moon which reflects it to us, and of necessity the Earth reflects the Sun's light to the Moon as well: it's no farther from the Earth to the Moon than from the Moon to the Earth." "But," said the Marquise, "is the Earth as suited as the Moon to reflect the Sun's light?" "I see you're still on the side of the Moon," I answered, "and hard put to rid yourself of all that lingering esteem. Light is composed of little balls that bounce off solid objects in another direction, whereas they pass in a straight line through those that give them entrance, such as air or glass. So what makes the Moon shed light on us is that it's a firm, solid body, which reflects these balls to us. Now I know you won't disagree that the Earth has this same firmness and solidity.... "I'll bet that I am going to make you admit, against all reason, that some day there might be communication between the Earth and the Moon. Take your mind back to the state America was in before it was discovered by Christopher Columbus. Its inhabitants lived in extreme ignorance. Far from understanding the sciences, they knew nothing of the simplest most necessary arts. They went naked, and had no weapons but the bow; they had never conceived that men could be carried by animals; they regarded the sea as a vast place, forbidden to men, which joined the sky, beyond which there was nothing.... "If they'd been told that there was another sort of navigation incomparably more perfect, by which one could cross this infinite expanse of water from whatever side and in whatever direction one wished, that one could stay quite still in the middle of turbulent currents, that one could control the speed at which he travelled, and finally that this sea, vast as it is, was no obstacle to the communication of people, providing only that people were there on the other side, you can be sure they'd never have believed it. "But one fine day the strangest and least expected sight in the world appears. Great enormous bodies which seem to have white wings and fly on the water, which spew out fire on all sides, and which throw up on the shore unknown people all covered with iron scales guiding as they come monsters which run beneath them, and carrying lightning bolts in their hands with which they strike to the earth all who resist. Where did they come from? Who brought them over the seas? Who put fire in their keeping? Are they gods? Are these the children of the Sun? For surely they're not men. "I don't know, Madame, if you grasp the surprise of these Americans as I do, but never in the world could there have been another to equal it. After that, I would no longer want to swear that there couldn't be communication between the Earth and the Moon some day. Could the Americans have believed anyone who said there could be any between America and a Europe that they didn't even know about? True it will be necessary to cross the great expanse of air and sky between the Earth and the Moon. But did the great seas seem to the Americans any more likely to be crossed?" "Really," said the Marquise, staring at me. "You are mad." "Who's arguing?" I answered. "But I want to prove it to you," she replied. "I'm not satisfied with your admission. The Americans were so ignorant that they hadn't the slightest suspicion that anyone could make roads across such vast seas. But we, who have more knowledge, would have considered the idea of traveling in the air if it could actually be done." "We're doing more than just guessing that it's possible," I replied. "We're beginning to fly a bit now; a number of different people have found the secret of strapping on wings that hold them up in the air, and making them move, and crossing over rivers or flying from one belfry to another. Certainly it's not been the flight of an eagle, and several times it's cost these fledglings an arm or a leg; but still these represent only the first planks that were placed in the water, which were the beginning of navigation. From those planks it was a long way to the big ships that could sail around the world. Still, little by little the big ships have come. "The art of flying has only just been born; it will be perfected, and some day we'll go to the Moon. Do we presume to have discovered all things, or to have taken them to the point where we can add nothing? For goodness sake, let's admit that there'll still be something left for future centuries to do." "I'll admit nothing," she said, "but that you'll never fly in any way that won't risk your neck." "Well," I answered her, "if you want us always to fly badly here, at least they may fly better on the Moon; its inhabitants are bound to be more suited to the mob than we are. It doesn't matter, after all, whether we go there or they come here, and we'll be just like the Americans who couldn't imagine such a thing as sailing when people were sailing so well at the other end of the world." "Have the people on the Moon already come?" she replied, nearly angry. "The Europeans weren't in America until after six thousand years," I said, breaking into laughter; "it took that much time for them to perfect navigation to the point where they could cross the ocean. Perhaps the people on the Moon already know how to make little trips through the air; right now they're practicing. When they're more experienced and skillful we'll see them. with God knows what surprise." "You're impossible," she said, "pushing me to the limit with reasoning as shallow as this." "If you resist me," I replied, "I know what I'll add to strengthen it. Notice how the world grows little by little. The Ancients held that the tropical and frigid zones could not be inhabited, because of excessive heat or cold; and in the Romans' time the overall map of the world hardly extended beyond their empire, which was impressive in one sense and indicated considerable ignorance in another. Meanwhile, men continued to appear in very hot and very cold lands, and so the world grew. "Following that, it was judged that the ocean covered all the Earth except what of it was then known; there were no Antipodes, for no one had ever spoken of them, and after all, wouldn't they have had their feet up and heads down? Yet after this fine conclusion the Antipodes were discovered all the same. A new revision of the map: a new half of the world. You understand me, Madame; these Antipodes that were found, contrary to all expectations, should teach us to be more cautious in our judgments. "Perhaps when the world has finished growing for us, we'll begin to know the Moon. We're not there yet because all the world isn't discovered yet, and apparently this must be done in order. When we've become really familiar with our home, we'll be permitted to know that of our neighbors, the people on the Moon." "Truly," said the Marquise, looking closely at me, "I find you're so immersed in this subject that it is not possible that you do not honestly believe everything you've said to me." "I'd be quite put out if you thought so," I answered. "I only want to make you see that one can support a whimsical theory well enough to perplex a clever person, but not enough to persuade her. Only the truth can persuade, and it needs to bring no array of proofs with it. Truth enters the mind so naturally that learning it for the first time seems merely like remembering it."... |

"I've great news to tell you," I said to her. "The Moon I was describing yesterday, which to all appearances was inhabited, may not be so after all; I've thought of something that puts those inhabitants in danger." "I'll put up with this no longer," she answered. "Yesterday you'd prepared me to see these people come here any day now, and today they won't even be in the universe? You'll not toy with me any longer; you've made me believe in the inhabitants of the Moon, I've overcome the trouble I had with it, and I will believe in them.... Are we not to think of the Moon as we did of Saint-Denis?" "No," I answered, "because the Moon doesn't resemble the Earth as much as Saint-Denis resembles Paris. The Sun draws mists and vapors from the land and water which, rising in the air to a certain height, come together to form the clouds.... The Moon must be some mass of rock and marble where there's no evaporation...." "But is this enough," she asked, "to make us abandon the inhabitants of the Moon?... Let's preserve them or annihilate them forever and not discuss it anymore -- but let's preserve them if possible. I've taken a liking to them that I'd be sorry to lose." "Then I won't leave the Moon deserted," I replied. "Let's repopulate her to give you pleasure.... Perhaps, then, the vapors that come from the Moon may not gather around her in clouds.... It's sufficient for this that the air (with which the Moon is apparently surrounded in her own way as the Earth is in its way) be a little different from our air, and the vapors of the Moon a little different from our vapors, which is something quite reasonable...." "I'm very happy again that you've given the Moon back her inhabitants [she said]. I'm very happy, too, that you've given her air of her own sort to envelop her, because it would seem to me from now on that without it a planet would be too naked." "These two different airs," I replied, "help to hinder communication between the two planets. If it were only a matter of flying, how do we know, as I told you yesterday, that we won't fly well enough some day? I confess, though, that it hardly seems likely. The great distance from the Moon to the Earth would still be a difficulty to overcome, and a considerable one, but even if it were not there, and even if the two planets were very close together, it would be impossible to pass from the Moon's air to the Earth's air. "Water is the fishes' air. It's not the distance that impedes them, it's that each is imprisoned by the air it breathes. We find that ours is a thicker and a heavier mixture of vapors than that of the Moon. On this account, an inhabitant of the Moon who arrived in the confines of our world would drown as soon as he entered our air, and we'd see him fall dead on the ground." "Oh, how I could wish," cried the Marquise, "for some great shipwreck that scattered a good number of those people here, so that we could examine their astonishing features at our ease." "But," I replied, "what if they were skillful enough to navigate on the outer surface of our air, and from there, through their curiosity to see us, they angled for us like fish? Would that please you?" "Why not?" she answered, laughing. "As for me, I'd put myself into their nets of my own volition just to have the pleasure of seeing those who caught me." "Consider," I answered, "that you'd be awfully sick on arriving at the top of our atmosphere. It's not really breathable for us to its full limits, far from it. It scarcely is on top of certain mountains.... So there are many natural barriers that forbid us to leave our world and to enter that of the Moon. At least we can try to console ourselves by surmising what we can of that world.... "[A]ll the planets are of the same nature, all opaque bodies that receive light only from the Sun and reflect it from one to the other, and have nothing but the same motions.... Yet we are expected to believe that these great bodies should have been fashioned not to be inhabited, that this should be their natural condition, and that there should be an exception made in favor of the Earth alone. Let anyone who wishes to believe, believe that; for me, I can't bring myself to do it.... "I still find it would be very strange that the Earth was as populated as it is, and the other planets weren't at all, for you mustn't think that we see all those who inhabit the Earth; there are as many species of invisible animals as visible. We see from the elephant down to the mite; there our sight ends. But beyond the mite an infinite multitude of animals begins for which the mite is an elephant, and which can't be perceived with ordinary eyesight. We've see with lenses many liquids filled with little animals that one would never have suspected lived there, and there's some indication that the taste they provide for our senses comes from the stings these little animals make on the tongue and the palate. Mix certain things in some of these liquids, or expose them to the Sun, or let them putrefy, and right away you'll see new species of little animals. "Many bodies that appear solid are nothing but a mass of these imperceptible animals, who find enough freedom of movement there as is necessary for them. A tree leaf is a little world inhabited by invisible worms, and it seems to them a vast expanse where they learn of mountains and abysses, and where there is no more communication between worms living on one side of the leaf and on the other than there is between us and the Antipodes. "All the more reason, it seems to me, why a huge planet will be an inhabited world. Even in very hard kinds of rock we've found innumerable small worms. Living in imperceptible gaps and feeding themselves by gnawing on the substance of the stone. Imagine how many of these little worms there may be, and how many years they've subsisted on the mass of a grain of sand. Following this example, even if the Moon were only a mass of rocks, I'd sooner have her gnawed by her inhabitants than not put any there at all. "In short, everything is living, everything is animate. Take all these species of animals newly discovered, and perhaps those that we easily imagine which are yet to be discovered, along with those that we've always seen, and you'll surely find that the Earth is well populated. Nature has distributed the animals so liberally that she doesn't even mind that we can only see half of them. Can you believe that after she had pushed her fecundity here to excess, she'd been so sterile toward all other planets as not to produce anything living?"... |

"There is no hope of placing inhabitants [on the Sun, I said.]... [T]he Sun isn't a body of the same sort as the Earth or the other planets. He's the source of all that light which the planets can only reflect to one another after having received it.... The Sun alone draws this precious substance from himself; he throws it out forcefully on all sides.... That's why the Sun is placed in the center, which is the most convenient place from which to distribute the light equally and animate everything by its heat.... Mars has nothing curious that I know of; its days are not quite an hour longer than ours, and its years the value of two of ours. It's smaller than the Earth, it sees the Sun a little less large and bright than we see it; in sum, Mars isn't worth the trouble of stopping there. But what a pretty thing Jupiter is, with its four moons or satellites!...." |

|

"Are you going to tell me [she said,] 'The fixed stars are suns, too; our Sun is the center of a vortex which rotates around it; why shouldn't each fixed star also be the center of a vortex which moves about it? Our Sun has planets which it lights; why shouldn't each fixed star have some which it lights too?'" "I can only answer," I told her, "what Phaedra said to Oenone: 'You said it!'" "But," she replied, "here's a universe so large that I'm lost, I no longer know where I am, I'm nothing. What, is everything to be divided into vortices, thrown together in confusion? Each star will be the center of a vortex, perhaps as large as ours? All this immense space which holds our Sun and our planets will be merely a small piece of the universe? As many spaces as there are fixed stars? This confounds me -- troubles me -- terrifies me." "And as for me," I answered, "this puts me at my ease. When the sky was only this blue vault, with the stars nailed to it, the universe seemed small and narrow to me; I felt oppressed by it. Now that they've given infinitely greater breadth and depth to this vault by dividing it into thousands and thousands of vortices, it seems to me that I breathe more freely, that I'm in a larger air, and certainly the universe has a completely different magnificence. Nature has held back nothing to produce it; she's made a profusion of riches altogether worthy of her. Nothing is so beautiful to visualize as this prodigious number of vortices, each with a sun at its center making planets rotate around it. The inhabitants of a planet in one of these infinite vortices see on all sides the lighted centers of the vortices surrounding them, but aren't abler to see their planets which, having only a feeble light borrowed from their sun, don't send it beyond their own world."...

|

|