Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

![]()

Lecture 11. Seeing Old Things in New Ways.

![]()

Saturn |

Changes in Saturn's appearance based on observations by Galileo (~1616) |

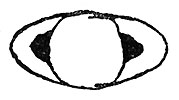

Comparison of observations of Saturn by Galileo, Scheiner, Hevelius and others from 1616-1655, |

Huygens was fascinated by Saturn's unusual and continually changing appearance. While making regular observations of the planet in 1655, his attention was drawn to a bright star that appeared to tag along with Saturn. Just like the so-called Medicean stars orbited Jupiter, this star moved around Saturn in a regular periodic way leading Huygens to conclude that it was a moon (now known as Titan). |

Huygens' comparison of Saturn's size with that of Earth (Tellus) and the Moon (Luna). To see more detail in this unusual planet, Huygens constructed a telescope with greater magnifying power. In 1656, he noted that Saturn is surrounded by a detached ring. In 1659, he published Systema Saturnium in which he announced his explanation for Saturn's changing appearance: unlike all other planets that had been observed telescopically, Huygens claimed that Saturn is encircled by a detached ring tilted about 27° to the plane of the ecliptic. |

In this famous diagram, Huygens showed how the axial tilts of both Earth and Saturn combine with their orbital motions around the Sun to produce the cyclical pattern of change in Saturn's appearance. |

New and Improved Telescopes |

| After reading of Galileo's remarkable telescopic discoveries, many individuals

wanted to see these celestial wonders for themselves. And they wanted

to see them better. To do this required improving the quality

of the lenses in a telescope's optical system.

Lenses have curved surfaces. When light travels through a lens it is dispersed, that is, it separates into a rainbow of colors. Dispersion interferes with the creation of a clear image. This distortion is called chromatic aberration. One way to reduce the effect of chromatic aberration in a telescope is to use an objective lens (the large lens closest to the object being viewed) that has very little curvature. A lens with nearly-flat surfaces will have a very long focal length, that is, it will form images at a great distance. It's a bit of a challenge to view an image formed by such a lens. Holding an eyepiece near an image is easier when it has been produced by a shorter focal length objective. You can construct a tube to keep the objective lens and the eyepiece at just the right distance from one another to produce the best images. But with a long focal length lens, the observer must stand far away from the lens in order to view the image it has formed. Encasing an optical system like this in a tube would create a heavy and unwieldy instrument. So why not make a telescope without a tube! These so-called "aerial" telescopes became all the rage in the second half of the seventeenth century. |

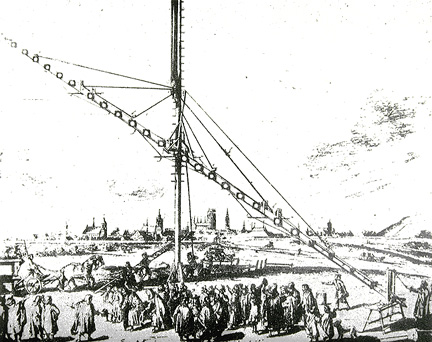

Christiaan Huygens' 123-foot "aerial" telescope.

The 150-ft aerial telescope of astronomer Johannes Hevelius (1611-1687) of Danzig (Gdansk) |

William Herschel (1738-1822)

|

|

Notable Events in William Herschel's Life |

|

| 1738 | born in Hanover, Germany |

| 1757 | emigrated to England

pursued career as music teacher and performer compositions include:

|

| 1766 | took position as organist in Bath

made his first entry in an astronomical diary |

| 1772 | sister, Caroline (1750-1848), joins him in Bath |

| 1773 | purchased book on astronomy

began constructing his own telescopes |

William Herschel's 7-ft reflecting telescope |

|

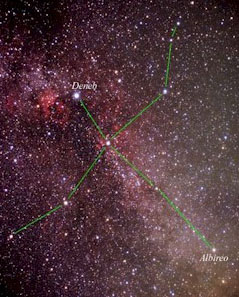

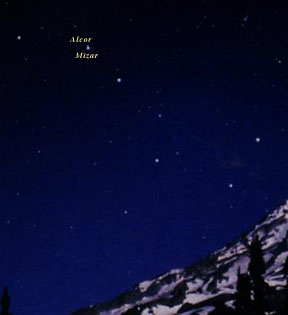

Hoping to detect and measure a slight shift in stellar positions (parallax) as the Earth orbits the Sun, Herschel began "sweeping" the heavens in search of close pairs of stars: |

|

|

|

|

|

|

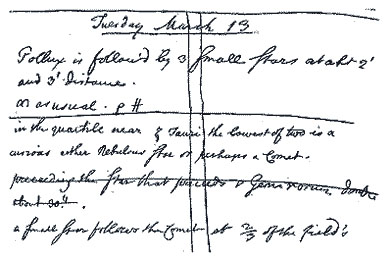

On 13 March 1781, during one of his routine "sweeps", Herschel observed "a curious rather Nebulous star or perhaps a Comet" in the constellation

Taurus.

Careful observation of this unusual object over the next few weeks convinced Herschel that he had found a new planet. He initially suggested naming the planet Georgium Sidus (George's Star) in honor of King George III of England. French astronomers, meanwhile, called it Herschel. German astronomer, Johann Elert Bode (1747-1826) suggested naming it Uranus, after the mythological god of the heavens and father of Saturn.

|

|

In 1783, Herschel completed work on his new 20-ft reflecting telescope and undertook a celestial census of the entire sky in order to determine the "construction of the heavens."

William Herschel's 20-ft telescope. |

|

Herschel's "star-gaging" assumptions:

(variations in brightness are due to variations in distance)

(thickness of the cluster in any given part of the sky can be deduced from the numbers of stars)

|

| In 1788, Herschel completed work on a 40-ft reflecting telescope.

Herschel's 40-ft telescope With this instrument, Herschel found he could now see MORE STARS!!

|

|

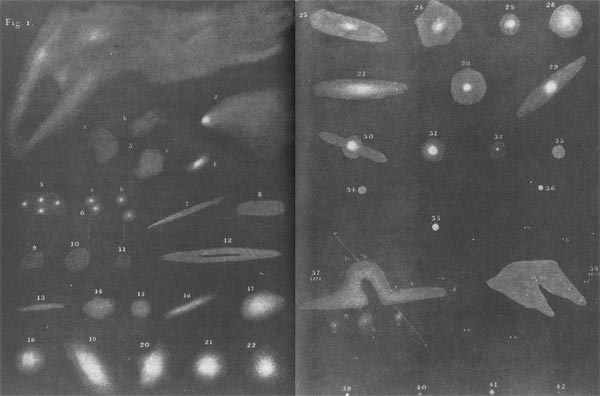

| In 1811, Herschel published the drawings shown below in the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society to exhibit the rich variety of nebula types. |

Cycle of Growth and Decay in

the Celestial Garden |

|

|