Thirteen hundred and forty-eight years had already passed after the

fruitful Incarnation of the Son of God when into the distinguished city

of Florence, more noble than any other Italian city, there came the deadly

pestilence. It started in the East, either because of the influence

of heavenly bodies or because of God's just wrath as a punishment to mortals

for our wicked deeds, and it killed an infinite number of people.

Without pause it spread from one place and it stretched its miserable

length over the West. And against this pestilence no human wisdom

or foresight was of any avail; quantities of filth were removed from the

city by officials charged with this task; the entry of any sick person

into the city was prohibited; and many directives were issued concerning

the maintenance of good health. Nor were the humble supplications,

rendered not once but many times to God by pious people, through public

processions or by other means, efficacious; for almost at the beginning

of springtime of the year in question the plague began to show its sorrowful

effects in an extraordinary manner.

It did not act as it had done in the East, where bleeding from the nose

was a manifest sign of inevitable death, but it began in both men and women

with certain swellings either in the groin or under the armpits, some of

which grew to the size of a normal apple and others to the size of an egg

(more or less), and the people called them gavoccioli.

And from the two parts of the body already mentioned, within a brief

space of time, the said deadly gavoccioli began to spread indiscriminately

over every part of the body; and after this, the symptoms of the illness

changed to black or livid spots appearing on the arms and thighs, and on

every part of the body, some large ones and sometimes many little ones

scattered all around. And just as the gavoccioli were originally,

and still are, a very certain indication of impending death, in like manner

these spots came to mean the same thing for whoever had them.

Neither a doctor's advice nor the strength of medicine could do anything

to cure this illness; on the contrary, either the nature of the illness

was such that it afforded no cure, or else the doctors were so ignorant

that they did not recognize its cause and, as a result, could not prescribe

the proper remedy (in fact, the number of doctors, other than the well-trained,

was increased by a large number of men and women who had never had any

medical training); at any rate, few of the sick were ever cured, and almost

all died after the third day of the appearance of the previously described

symptoms (some sooner, others later), and most of them died without fever

or any other side effects.

This pestilence was so powerful that it was communicated to the healthy

by contact with the sick, the way a fire close to dry or oily things will

set them aflame. And the evil of the plague went even further:

not only did talking to or being around the sick bring infection and a

common death, but also touching the clothes of the sick or anything touched

or used by them seemed to communicate this very disease to the person involved.

What I am about to say is incredible to hear, and if I and others had

not witnessed it with our own eyes, I should not dare believe it (let alone

write about it), no matter how trustworthy a person I might have heard

it from. Let me say, then, that the power of the plague described

here was of such virulence in spreading from one person to another that

not only did it pass from one man to the next, but, what's more, it was

often transmitted from the garments of a sick or dead man to animals that

not only became contaminated by the disease, but also died within a brief

period of time. My own eyes, as I said earlier, witnessed such a

thing one day: when the rags of a poor man who died of this disease

were thrown into the public street, two pigs came upon them, as they are

wont to do, and first with their snouts and then with their teeth they

took the rags and shook them around; and within a short time, after a number

of convulsions, both pigs fell dead upon the ill-fated rags, as if they

had been poisoned.

From these and many similar or worse occurrences there came about such

fear and such fantastic notions among those who remained alive that almost

all of them took a very cruel attitude in the matter; that is, they completely

avoided the sick and their possessions; and in so doing, each one believed

that he was protecting his good health.

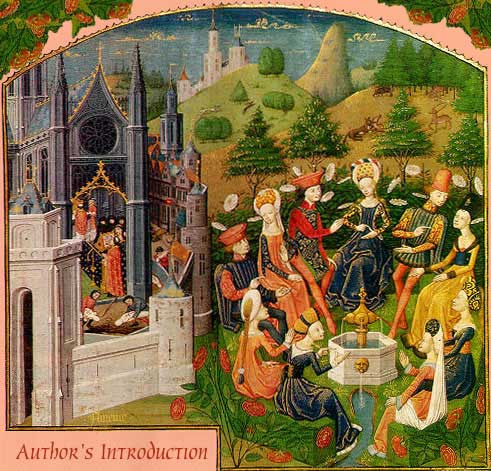

There were some people who thought that living moderately and avoiding

all superfluity might help a great deal in resisting this disease, and

so, they gathered in small groups and lived entirely apart from everyone

else. They shut themselves up in those houses where there were no

sick people and where one could live well by eating the most delicate of

foods and drinking the finest of wines (doing so always in moderation),

allowing no one to speak about or listen to anything said about the sick

and the dead outside; these people lived, spending their time with music

and other pleasures that they could arrange.

Others thought the opposite: they believed that drinking too much,

enjoying life, going about singing and celebrating, satisfying in every

way the appetites as best one could, laughing, and making light of everything

that happened was the best medicine for such a disease; so they practiced

to the fullest what they believed by going from one tavern to another all

day and night, drinking to excess; and often they would make merry in private

homes, doing everything that pleased or amused them the most. This

they were able to do easily, for everyone felt he was doomed to die and,

as a result, abandoned his property, so that most of the houses had become

common property, and any stranger who came upon them used them as if he

were their rightful owner.

In addition to this bestial behavior, they always managed to avoid the

sick as best they could. And in this great affliction and misery

of our city the revered authority of the laws, both divine and human, had

fallen and almost completely disappeared, for, like other men, the ministers

and executors of the laws were either dead or sick or so short of help

that it was impossible for them to fulfill their duties; as a result, everybody

was free to do as he pleased.

Many others adopted a middle course between the two attitudes just described:

neither did they restrict their food or drink so much as the first group

nor did they fall into such dissoluteness and drunkenness as the second;

rather, they satisfied their appetites to a moderate degree. They

did not shut themselves up, but went around carrying in their hands flowers,

or sweet-smelling herbs, or various kinds of spices; and often they would

put these things to their noses, believing that such smells were a wonderful

means of purifying the brain, for all the air seemed infected with the

stench of dead bodies, sickness, and medicines.

Others were of a crueler opinion (though it was, perhaps, a safer one):

they maintained that there was no better medicine against the plague than

to flee from it; and convinced of this reasoning, not caring about anything

but themselves, men and women in great numbers abandoned their city, their

houses, their farms, their relatives, and their possessions and sought

other places, and they went at least as far away as the Florentine countryside--as

if the wrath of God could not pursue them with this pestilence wherever

they went but would only strike those it found within the walls of the

city! Or perhaps they thought that Florence's last hour had come

and that no one in the city would remain alive.

And not all those who adopted these diverse opinions died, nor did they

all escape with their lives; on the contrary, many of those who thought

this way were falling sick everywhere, and since they had given, when they

were healthy, the bad example of avoiding the sick, they, in turn, were

abandoned and left to languish away without care.

The fact was that one citizen avoided another, that almost no one cared

for his neighbor, and that relatives rarely or hardly ever visited each

other--they stayed far apart. This disaster had struck such fear into

the hearts of men and women that brother abandoned brother, uncle abandoned

nephew, sister left brother, and very often wife abandoned husband, and -- even

worse, almost unbelievable -- fathers and mothers neglected to tend and care

for their children, as if they were not their own.

Thus, for the countless multitude of men and women who fell sick, there

remained no support except the charity of their friends (and these were

few) or the avarice of servants, who worked for inflated salaries and indecent

periods of time and who, in spite of this, were few and far between; and

those few were men or women of little wit (most of them not trained for

such service) who did little else but hand different things to the sick

when requested to do so or watch over them while they died, and in this

service, they very often lost their own lives and their profits.

And since the sick were abandoned by their neighbors, their parents,

and their friends and there was a scarcity of servants, a practice that

was almost unheard of before spread through the city: when a woman

fell sick, no matter how attractive or beautiful or noble she might be,

she did not mind having a manservant (whoever he might be, no matter how

young or old he was), and she had no shame whatsoever in revealing any

part of her body to him--the way she would have done to a woman -- when the

necessity of her sickness required her to do so. This practice was,

perhaps, in the days that followed the pestilence, the cause of looser

morals in the women who survived the plague.

And so, many people died who, by chance, might have survived if they

had been attended to. Between the lack of competent attendants, which

the sick were unable to obtain, and the violence of the pestilence, there

were so many, many people who died in the city both day and night that

it was incredible just to hear this described, not to mention seeing it!

Therefore, out of sheer necessity, there arose among those who remained

alive customs which were contrary to the established practices of the time.

It was the custom, as it is again today, for the women, relatives, and

neighbors to gather together in the house of a dead person and there to

mourn with the women who had been dearest to him; on the other hand, in

front of the deceased's home, his male relatives would gather together

with his male neighbors and other citizens, and the clergy also came (many

of them, or sometimes just a few) depending upon the social class of the

dead man. Then, upon the shoulders of his equals, he was carried

to

the church chosen by him before death with the funeral pomp of candles

and chants.

With the fury of the pestilence increasing, this custom, for the most

part, died out and other practices took its place. And so, not only

did people die without having a number of women around them, but there

were many who passed away without even having a single witness present,

and very few were granted the piteous laments and bitter tears of their

relatives; on the contrary, most relatives were somewhere else, laughing,

joking, and amusing themselves; even the women learned this practice too

well, having put aside, for the most part, their womanly compassion for

their own safety.

Very few were the dead whose bodies were accompanied to the church by

more than ten or twelve of their neighbors, and these dead bodies were

not even carried on the shoulders of honored and reputable citizens but

rather by gravediggers from the lower classes that were called becchini.

Working for pay, they would pick up the bier and hurry it off, not to the

church the dead man had chosen before his death but, in most cases, to

the church closest by, accompanied by four or six churchmen with just a

few candles, and often none at all. With the help of these becchini,

the churchmen would place the body as fast as they could in whatever unoccupied

grave they could find, without going to the trouble of saying long or solemn

burial services.

The plight of the lower class and, perhaps, a large part of the middle

class, was even more pathetic: most of them stayed in their homes

or neighborhoods either because of their poverty or their hopes for remaining

safe, and every day they fell sick by the thousands; and not having servants

or attendants of any kind, they almost always died. Many ended their

lives in the public streets, during the day or at night, while many others

who died in their homes were discovered dead by their neighbors only by

the smell of their decomposing bodies. |