Infectious and Epidemic Disease in History

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

excerpt from The Chronical (c.1359) by Jean de Venette (d.1369) |

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

excerpt from The Chronical (c.1359) by Jean de Venette (d.1369) |

In 1348 the people of France, and of virtually the whole world, were assailed by something more than war. For just as famine had befallen them ... and then war ... so now pestilences broke out in various parts of the world.

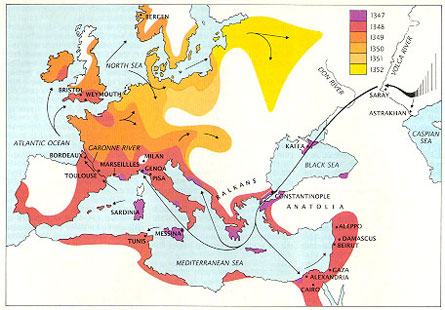

In the August of that year a very large and bright star was seen in the west over Paris, after vespers, when the sun was still shining but beginning to set. It was not as high in the heavens as the rest of the stars; on the contrary, it seemed rather near. And as the sun set and night approached the star seemed to stay in one place, as I and my brethren observed. Once night had fallen, as we watched and greatly marveled, the great star sent out many separate beams of light, and after shooting out rays eastwards over Paris it vanished totally: there one minute, gone the next. Whether it was a comet or something else -- perhaps something condensed from some sort of exhalations which then returned to vapor -- I leave to the judgment of astronomers. But it seems possible that it presaged the incredible pestilence which soon followed in Paris and throughout the whole of France, as I shall describe. As a result of that pestilence a great many men and women died that year and the next in Paris and throughout the kingdom of France, as they also did in other parts of the world. The young were more likely to die than the elderly, and did so in such numbers that burials could hardly keep pace. Those who fell ill lasted little more than two or three days, but died suddenly, as if in the midst of health -- for someone who was healthy one day could be dead and buried the next. Lumps suddenly erupted in their armpits or groin, and their appearance was an infallible sign of death. Doctors called this sickness or pestilence an epidemic. Such an enormous number of people died in 1348 and 1349 that nothing like it has been heard or seen or read about. And death and sickness came by imagination, or by contact with others and consequent contagion; for a healthy person who visited the sick hardly ever escaped death. In many towns and villages the result was that the cowardly priests took themselves off, leaving the performance of spiritual offices to the regular clergy, who tended to be more courageous. To be brief, in many places not two men remained alive out of twenty. The mortality was so great that, for a considerable period, more than 500 bodies a day were being taken in carts from the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris for burial in the cemetery of the Holy Innocents. The saintly sisters of the Hôtel-Dieu, not fearing death, worked sweetly and with great humility, setting aside considerations of earthly dignity. A great number of the sisters were called to a new life by death and now rest, it is piously believed, with Christ. It is said that this mortality began among the infidel and then traveled to Italy. Afterwards it crossed the mountains and arrived in Avignon, where it attacked various cardinals and carried off their entire households. Then it gradually advanced through Gascony and Spain and into France, advancing town by town, street by street, and finally from house to house -- or, rather, person to person. It then crossed into Germany, although it was less virulent there than with us. During the epidemic the Lord, of his goodness, deigned to confer such grace on those dying that, however suddenly they died, almost all of them faced death as joyfully as if they had been well prepared for it. Nor did anyone die without making confession and receiving the last sacrament So that more of those dying would make a good end, Pope Clement mercifully gave the confessors in numerous cities and villages the power to absolve the sins of the dying, so that as a result they died the more happily, leaving much of their land and goods to churches or religious orders since their right heirs had predeceased them. Men ascribed the pestilence to infected air or water, because there was no famine or lack of food at that time but, on the contrary, a great abundance. One result of this interpretation was that the infection and the sudden death which it brought, were blamed on the Jews, who were said to have poisoned wells and rivers and corrupted the air. Accordingly the whole world brutally rose against them and thousands were indiscriminately butchered, slaughtered and burnt alive by the Christians. The insane constancy shown by them and their wives was amazing. When Jews were being burnt mothers would throw their own children into the flames rather than risk them being baptized, and would then hurl themselves into the fire after them to burn with their husbands and children.

It was claimed that many wicked Christians were discovered poisoning wells in a similar fashion. But in truth, such poisonings, even if they really happened, could not have been solely responsible for so great a plague or killed so many people. There must have been some other cause such as, for instance, the will of God, or corrupt humors and the badness of air and earth; although perhaps such poisonings, where they did occur were a contributory factor. The mortality continued in France for most of 1348 and 1349 and then stopped, leaving many villages and many town houses virtually empty, stripped of their inhabitants. Then many houses fell quickly into ruin, including numerous houses in Paris, although the damage there was less than in many places. When the epidemic was over the men and women still alive married each other. Everywhere women conceived more readily than usual. None proved barren, on the contrary, there were pregnant women wherever you looked. Several gave birth to twins, and some to living triplets. But what is particularly surprising is that when the children born after the plague started cutting their teeth they commonly turned out to have only 20 or 22, instead of the 32 usual before the plague. I am unsure what this means, unless it is, as some men say, a sign that the death of infinite numbers of people, and their replacement by those who survived, has somehow renewed the world and initiated a new age. But if so, the world, alas, has not been made any better by its renewal. For after the plague men became more miserly and grasping, although many owned more than they had before. They were also more greedy and quarrelsome, involving themselves in brawls, disputes and lawsuits. Nor did the dreadful plague inflicted by God bring about peace between kings and lords. On the contrary, the enemies of the king of France and of the Church were stronger and more evil than before and stirred up wars by land and sea. Evil spread like wildfire. What was also amazing was that, in spite of there being plenty of everything, it was all twice as expensive: household equipment and foodstuffs, as well as merchandise, hired labor, farm workers and servants. The only exception was property and houses, of which there is a glut to this day. Also from that time charity began to grow cold, and wrongdoing flourished, along with sinfulness and ignorance -- for few men could be found in houses, towns or castles who were able or willing to instruct boys in the rudiments of Latin. |

|

| Go to: |

|

|