SPRING QUARTER, 2006

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

| Week 8. Behavior excerpts from

|

CHAPTER 1.

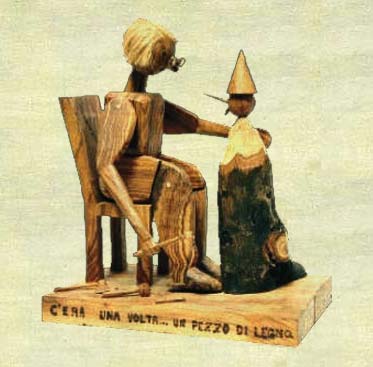

How it happened that Mastro Cherry, carpenter, found a piece of wood that wept and laughed like a child

...Once upon a time there was a piece of wood. It was not an expensive piece of wood. Far from it. Just a common block of firewood, one of those thick, solid logs that are put on the fire in winter to make cold rooms cozy and warm.

I do not know how this really happened, yet the fact remains that one fine day this piece of wood found itself in the shop of an old carpenter. His real name was Mastro Antonio, but everyone called him Mastro Cherry, for the tip of his nose was so round and red and shiny that it looked like a ripe cherry.

As soon as he saw that piece of wood, Mastro Cherry was filled with joy. Rubbing his hands together happily, he mumbled half to himself:

"This has come in the nick of time. I shall use it to make the leg of a table."

He grasped the hatchet quickly to peel off the bark and shape the wood. But as he was about to give it the first blow, he stood still with arm uplifted, for he had heard a wee, little voice say in a beseeching tone: "Please be careful! Do not hit me so hard!"

What a look of surprise shone on Mastro Cherry's face! His funny face became still funnier.

He turned frightened eyes about the room to find out where that wee, little voice had come from and he saw no one! He looked under the bench -- no one! He peeped inside the closet -- no one! He searched among the shavings -- no one! He opened the door to look up and down the street -- and still no one!

"Oh, I see!" he then said, laughing and scratching his Wig. "It can easily be seen that I only thought I heard the tiny voice say the words! Well, well -- to work once more."

He struck a most solemn blow upon the piece of wood.

"Oh, oh! You hurt!" cried the same far-away little voice.

Mastro Cherry grew dumb, his eyes popped out of his head, his mouth opened wide, and his tongue hung down on his chin.

As soon as he regained the use of his senses, he said, trembling and stuttering from fright:

"Where did that voice come from, when there is no one around? Might it be that this piece of wood has learned to weep and cry like a child? I can hardly believe it. Here it is -- a piece of common firewood, good only to burn in the stove, the same as any other. Yet -- might someone be hidden in it? If so, the worse for him. I'll fix him!"

With these words, he grabbed the log with both hands and started to knock it about unmercifully. He threw it to the floor, against the walls of the room, and even up to the ceiling.

He listened for the tiny voice to moan and cry. He waited two minutes -- nothing; five minutes -- nothing; ten minutes -- nothing.

"Oh, I see," he said, trying bravely to laugh and ruffling up his wig with his hand. "It can easily be seen I only imagined I heard the tiny voice! Well, well -- to work once more!"

The poor fellow was scared half to death, so he tried to sing a gay song in order to gain courage.

He set aside the hatchet and picked up the plane to make the wood smooth and even, but as he drew it to and fro, he heard the same tiny voice. This time it giggled as it spoke:

"Stop it! Oh, stop it! Ha, ha, ha! You tickle my stomach."

This time poor Mastro Cherry fell as if shot. When he opened his eyes, he found himself sitting on the floor.

His face had changed; fright had turned even the tip of his nose from red to deepest purple.

![]()

CHAPTER 2.

Mastro Cherry gives the piece of wood to his friend Geppetto...

In that very instant, a loud knock sounded on the door. "Come in," said the carpenter, not having an atom of strength left with which to stand up.

At the words, the door opened and a dapper little old man came in. His name was Geppetto, but to the boys of the neighborhood he was Polendina, [polenta; cornmeal mush] on account of the wig he always wore which was just the color of yellow corn. Geppetto had a very bad temper. Woe to the one who called him Polendina! He became as wild as a beast and no one could soothe him.

"Good day, Mastro Antonio," said Geppetto. "What are you doing on the floor?"

"I am teaching the ants their A B C's."

"Good luck to you!"

"What brought you here, friend Geppetto?"....

"This morning a fine idea came to me."

"Let's hear it."

"I thought of making myself a beautiful wooden Marionette. It must be wonderful, one that will be able to dance, fence, and turn somersaults. With it I intend to go around the world, to earn my crust of bread and cup of wine. What do you think of it?"

"Bravo, Polendina!" cried the same tiny voice which came from no one knew where.

On hearing himself called Polendina, Mastro Geppetto turned the color of a red pepper and, facing the carpenter, said to him angrily:

"Why do you insult me?"

"Who is insulting you?"

"You called me Polendina."

"I did not."

"I suppose you think I did! Yet I KNOW it was you."

"No!"

"Yes!"

"No!"

"Yes!"

And growing angrier each moment, they went from words to blows, and finally began to scratch and bite and slap each other.

When the fight was over, ... [t]he two little old men ... shook hands and swore to be good friends for the rest of their lives.

"Well then, Mastro Geppetto," said the carpenter, to show he bore him no ill will, "what is it you want?"

"I want a piece of wood to make a Marionette. Will you give it to me?"

Mastro Antonio, very glad indeed, went immediately to his bench to get the piece of wood which had frightened him so much. But as he was about to give it to his friend, with a violent jerk it slipped out of his hands and hit against poor Geppetto's thin legs.

"Ah! Is this the gentle way, Mastro Antonio, in which you make your gifts? You have made me almost lame!"

"I swear to you I did not do it!"

"It was I, of course!"

"It's the fault of this piece of wood."

"You're right; but remember you were the one to throw it at my legs."

|

"I did not throw it!"

"Liar!"

"Geppetto, do not insult me or I shall call you Polendina."

"Idiot."

"Polendina!"

"Donkey!"

"Polendina!"

"Ugly monkey!"

"Polendina!"

On hearing himself called Polendina for the third time, Geppetto lost his head with rage and threw himself upon the carpenter. Then and there they gave each other a sound thrashing.

After this fight, Mastro Antonio had two more scratches on his nose, and Geppetto had two buttons missing from his coat. Thus having settled their accounts, they shook hands and swore to be good friends for the rest of their lives.

Then Geppetto took the fine piece of wood, thanked Mastro Antonio, and limped away toward home.

![]()

CHAPTER 3.

...Geppetto fashions the Marionette and calls it Pinocchio...

...As soon as he reached home, Geppetto took his tools and began to cut and shape the wood into a Marionette.

"What shall I call him?" he said to himself. "I think I'll call him PINOCCHIO [literally, pine-nut]. This name will make his fortune. I knew a whole family of Pinocchi once -- Pinocchio the father, Pinocchia the mother, and Pinocchi the children -- and they were all lucky. The richest of them begged for his living."

After choosing the name for his Marionette, Geppetto set seriously to work to make the hair, the forehead, the eyes. Fancy his surprise when he noticed that these eyes moved and then stared fixedly at him. Geppetto, seeing this, felt insulted and said in a grieved tone:

"Ugly wooden eyes, why do you stare so?"

There was no answer.

After the eyes, Geppetto made the nose, which began to stretch as soon as finished. It stretched and stretched and stretched till it became so long, it seemed endless.

Poor Geppetto kept cutting it and cutting it, but the more he cut, the longer grew that impertinent nose. In despair he let it alone.

Next he made the mouth.

No sooner was it finished than it began to laugh and poke fun at him.

|

"Stop laughing!" said Geppetto angrily; but he might as well have spoken to the wall.

"Stop laughing, I say!" he roared in a voice of thunder.

The mouth stopped laughing, but it stuck out a long tongue.

Not wishing to start an argument, Geppetto made believe he saw nothing and went on with his work. After the mouth, he made the chin, then the neck, the shoulders, the stomach, the arms, and the hands.

As he was about to put the last touches on the finger tips, Geppetto felt his wig being pulled off. He glanced up and what did he see? His yellow wig was in the Marionette's hand. "Pinocchio, give me my wig!"

But instead of giving it back, Pinocchio put it on his own head, which was half swallowed up in it.

At that unexpected trick, Geppetto became very sad and downcast, more so than he had ever been before.

"Pinocchio, you wicked boy!" he cried out. "You are not yet finished, and you start out by being impudent to your poor old father. Very bad, my son, very bad!"

And he wiped away a tear.

The legs and feet still had to be made. As soon as they were done, Geppetto felt a sharp kick on the tip of his nose.

"I deserve it!" he said to himself. "I should have thought of this before I made him. Now it's too late!"

He took hold of the Marionette under the arms and put him on the floor to teach him to walk.

Pinocchio's legs were so stiff that he could not move them, and Geppetto held his hand and showed him how to put out one foot after the other.

When his legs were limbered up, Pinocchio started walking by himself and ran all around the room. He came to the open door, and with one leap he was out into the street. Away he flew!

Poor Geppetto ran after him but was unable to catch him, for Pinocchio ran in leaps and bounds, his two wooden feet, as they beat on the stones of the street, making as much noise as twenty peasants in wooden shoes.

"Catch him! Catch him!" Geppetto kept shouting. But the people in the street, seeing a wooden Marionette running like the wind, stood still to stare and to laugh until they cried.

At last, by sheer luck, a Carabineer [carabiniere; policeman] happened along, who, hearing all that noise, thought that it might be a runaway colt, and stood bravely in the middle of the street, with legs wide apart, firmly resolved to stop it and prevent any trouble. Pinocchio saw the Carabineer from afar and tried his best to escape between the legs of the big fellow, but without success.

The Carabineer grabbed him by the nose (it was an extremely long one and seemed made on purpose for that very thing) and returned him to Mastro Geppetto.

The little old man wanted to pull Pinocchio's ears. Think how he felt when, upon searching for them, he discovered that he had forgotten to make them!

All he could do was to seize Pinocchio by the back of the neck and take him home. As he was doing so, he shook him two or three times and said to him angrily:

"We're going home now. When we get home, then we'll settle this matter!"

Pinocchio, on hearing this, threw himself on the ground and refused to take another step. One person after another gathered around the two....

"Poor Marionette," called out a man. "I am not surprised he doesn't want to go home. Geppetto, no doubt, will beat him unmercifully, he is so mean and cruel!"

"Geppetto looks like a good man," added another, "but with boys he's a real tyrant. If we leave that poor Marionette in his hands he may tear him to pieces!"

They said so much that, finally, the Carabineer ended matters by setting Pinocchio at liberty and dragging Geppetto to prison. The poor old fellow did not know how to defend himself, but wept and wailed like a child and said between his sobs:

"Ungrateful boy! To think I tried so hard to make you a well-behaved Marionette! I deserve it, however! I should have given the matter more thought."

What happened after this is an almost unbelievable story, but you may read it, dear children, in the chapters that follow.

![]()

CHAPTER 4.

The story of Pinocchio and the Talking Cricket...

...[T]hat rascal, Pinocchio, free now from the clutches of the Carabineer, was running wildly across fields and meadows, taking one short cut after another toward home....

On reaching home, he found the house door half open. He slipped into the room, locked the door, and threw himself on the floor, happy at his escape.

But his happiness lasted only a short time, for just then he heard someone saying:

"Cri-cri-cri!"

"Who is calling me?" asked Pinocchio, greatly frightened.

"I am!"

Pinocchio turned and saw a large cricket crawling slowly up the wall.

"Tell me, Cricket, who are you?"

"I am the Talking Cricket and I have been living in this room for more than one hundred years."

"Today, however, this room is mine," said the Marionette, "and if you wish to do me a favor, get out now, and don't turn around even once."

"I refuse to leave this spot," answered the Cricket, "until I have told you a great truth."

"Tell it, then, and hurry."

"Woe to boys who refuse to obey their parents and run away from home! They will never be happy in this world, and when they are older they will be very sorry for it."

"Sing on, Cricket mine, as you please. What I know is, that tomorrow, at dawn, I leave this place forever. If I stay here the same thing will happen to me which happens to all other boys and girls. They are sent to school, and whether they want to or not, they must study. As for me, let me tell you, I hate to study! It's much more fun, I think, to chase after butterflies, climb trees, and steal birds' nests."

"Poor little silly! Don't you know that if you go on like that, you will grow into a perfect donkey and that you'll be the laughingstock of everyone?"

"Keep still, you ugly Cricket!" cried Pinocchio.

But the Cricket, who was a wise old philosopher, instead of being offended at Pinocchio's impudence, continued in the same tone:

"If you do not like going to school, why don't you at least learn a trade, so that you can earn an honest living?"

"Shall I tell you something?" asked Pinocchio, who was beginning to lose patience. "Of all the trades in the world, there is only one that really suits me."

|

"And what can that be?"

"That of eating, drinking, sleeping, playing, and wandering around from morning till night."

"Let me tell you, for your own good, Pinocchio," said the Talking Cricket in his calm voice, "that those who follow that trade always end up in the hospital or in prison."

"Careful, ugly Cricket! If you make me angry, you'll be sorry!"

"Poor Pinocchio, I am sorry for you."

"Why?"

"Because you are a Marionette and, what is much worse, you have a wooden head."

At these last words, Pinocchio jumped up in a fury, took a hammer from the bench, and threw it with all his strength at the Talking Cricket.

Perhaps he did not think he would strike it. But, sad to relate, my dear children, he did hit the Cricket, straight on its head.

With a last weak "cri-cri-cri" the poor Cricket fell from the wall, dead!....

![]()

CHAPTER 25.

Pinocchio promises the Fairy to be good ... and wishes to become a real boy

...[T]he little woman ... finally admitted that she was the little Fairy with Azure Hair....

"Do you remember? You left me when I was a little girl and now you find me a grown woman. I am so old, I could almost be your mother!"

"I am very glad of that, for then I can call you mother instead of sister. For a long time I have wanted a mother, just like other boys. But how did you grow so quickly?"

"That's a secret!"

"Tell it to me. I also want to grow a little. Look at me! I have never grown higher than a penny's worth of cheese."

"But you can't grow," answered the Fairy.

"Why not?"

"Because Marionettes never grow. They are born Marionettes, they live Marionettes, and they die Marionettes."

"Oh, I'm tired of always being a Marionette!" cried Pinocchio disgustedly. "It's about time for me to grow into a man as everyone else does."

"And you will if you deserve it -- "

"Really? What can I do to deserve it?"

"It's a very simple matter. Try to act like a well-behaved child."

"Don't you think I do?"

"Far from it! Good boys are obedient, and you, on the contrary -- "

"And I never obey."

"Good boys love study and work, but you -- "

"And I, on the contrary, am a lazy fellow and a tramp all year round."

"Good boys always tell the truth."

"And I always tell lies."

"Good boys go gladly to school."

"And I get sick if I go to school. From now on I'll be different."

"Do you promise?"

"I promise. I want to become a good boy and be a comfort to my father. Where is my poor father now?"

"I do not know."

"Will I ever be lucky enough to find him and embrace him once more?"

"I think so. Indeed, I am sure of it."

At this answer, Pinocchio's happiness was very great. He grasped the Fairy's hands and kissed them so hard that it looked as if he had lost his head....

"You will obey me always and do as I wish?"

"Gladly, very gladly, more than gladly!"

"Beginning tomorrow," said the Fairy, "you'll go to school every day."

Pinocchio's face fell a little.

"Then you will choose the trade you like best."

Pinocchio became more serious.

"What are you mumbling to yourself?" asked the Fairy.

"I was just saying," whined the Marionette in a whisper, "that it seems too late for me to go to school now."

"No, indeed. Remember it is never too late to learn."

"But I don't want either trade or profession."

"Why?"

"Because work wearies me!"

"My dear boy," said the Fairy, "people who speak as you do usually end their days either in a prison or in a hospital. A man, remember, whether rich or poor, should do something in this world. No one can find happiness without work. Woe betide the lazy fellow! Laziness is a serious illness and one must cure it immediately; yes, even from early childhood. If not, it will kill you in the end."

These words touched Pinocchio's heart. He lifted his eyes to his Fairy and said seriously: "I'll work; I'll study; I'll do all you tell me. After all, the life of a Marionette has grown very tiresome to me and I want to become a boy, no matter how hard it is. You promise that, do you not?"

"Yes, I promise, and now it is up to you."

![]()

CHAPTER 35.

In the Shark's body...

Pinocchio ... tottered away in the darkness and began to walk as well as he could toward the faint light which glowed in the distance.

As he walked his feet splashed in a pool of greasy and slippery water, which had such a heavy smell of fish fried in oil that Pinocchio thought it was Lent.

The farther on he went, the brighter and clearer grew the tiny light. On and on he walked till finally he found ... a little table set for dinner and lighted by a candle stuck in a glass bottle; and near the table sat a little old man, white as the snow, eating live fish. They wriggled so that, now and again, one of them slipped out of the old man's mouth and escaped into the darkness under the table.

At this sight, the poor Marionette was filled with such great and sudden happiness that he almost dropped in a faint. He wanted to laugh, he wanted to cry, he wanted to say a thousand and one things, but all he could do was to stand still, stuttering and stammering brokenly. At last, with a great effort, he was able to let out a scream of joy and, opening wide his arms he threw them around the old man's neck.

"Oh, Father, dear Father! Have I found you at last? Now I shall never, never leave you again!"

"Are my eyes really telling me the truth?" answered the old man, rubbing his eyes. "Are you really my own dear Pinocchio?"

"Yes, yes, yes! It is I! Look at me! And you have forgiven me, haven't you? Oh, my dear Father, how good you are! And to think that I -- Oh, but if you only knew how many misfortunes have fallen on my head and how many troubles I have had! Just think that on the day you sold your old coat to buy me my A-B-C book so that I could go to school, I ran away to the Marionette Theater and the proprietor caught me and wanted to burn me to cook his roast lamb! He was the one who gave me the five gold pieces for you, but I met the Fox and the Cat, who took me to the Inn of the Red Lobster. There they ate like wolves and I left the Inn alone and I met the Assassins in the wood. I ran and they ran after me, always after me, till they hanged me to the branch of a giant oak tree. Then the Fairy of the Azure Hair sent the coach to rescue me and the doctors, after looking at me, said, 'If he is not dead, then he is surely alive,' and then I told a lie and my nose began to grow. It grew and it grew, till I couldn't get it through the door of the room. And then I went with the Fox and the Cat to the Field of Wonders to bury the gold pieces. The Parrot laughed at me and, instead of two thousand gold pieces, I found none. When the Judge heard I had been robbed, he sent me to jail to make the thieves happy; and when I came away I saw a fine bunch of grapes hanging on a vine. The trap caught me and the Farmer put a collar on me and made me a watchdog. He found out I was innocent when I caught the Weasels and he let me go. The Serpent with the tail that smoked started to laugh and a vein in his chest broke and so I went back to the Fairy's house. She was dead, and the Pigeon, seeing me crying, said to me, 'I have seen your father building a boat to look for you in America,' and I said to him, 'Oh, if I only had wings!' and he said to me, 'Do you want to go to your father?' and I said, 'Perhaps, but how?' and he said, 'Get on my back. I'll take you there.' We flew all night long, and next morning the fishermen were looking toward the sea, crying, 'There is a poor little man drowning,' and I knew it was you, because my heart told me so and I waved to you from the shore -- "

"I knew you also," put in Geppetto, "and I wanted to go to you; but how could I? The sea was rough and the whitecaps overturned the boat. Then a Terrible Shark came up out of the sea and, as soon as he saw me in the water, swam quickly toward me, put out his tongue, and swallowed me as easily as if I had been a chocolate peppermint."

"And how long have you been shut away in here?"

"From that day to this, two long weary years -- two years, my Pinocchio, which have been like two centuries."

"And how have you lived? Where did you find the candle? And the matches with which to light it -- where did you get them?"

"You must know that, in the storm which swamped my boat, a large ship also suffered the same fate. The sailors were all saved, but the ship went right to the bottom of the sea, and the same Terrible Shark that swallowed me, swallowed most of it."

"What! Swallowed a ship?" asked Pinocchio in astonishment.

"At one gulp. The only thing he spat out was the main-mast, for it stuck in his teeth. To my own good luck, that ship was loaded with meat, preserved foods, crackers, bread, bottles of wine, raisins, cheese, coffee, sugar, wax candles, and boxes of matches. With all these blessings, I have been able to live happily on for two whole years, but now I am at the very last crumbs. Today there is nothing left in the cupboard, and this candle you see here is the last one I have."

"And then?"

"And then, my dear, we'll find ourselves in darkness."

"Then, my dear Father," said Pinocchio, "there is no time to lose. We must try to escape."

"Escape! How?"

"We can run out of the Shark's mouth and dive into the sea."

"You speak well, but I cannot swim, my dear Pinocchio."

"Why should that matter? You can climb on my shoulders and I, who am a fine swimmer, will carry you safely to the shore."

"Dreams, my boy!" answered Geppetto, shaking his head and smiling sadly. "Do you think it possible for a Marionette, a yard high, to have the strength to carry me on his shoulders and swim?"

"Try it and see! And in any case, if it is written that we must die, we shall at least die together."

Not adding another word, Pinocchio took the candle in his hand and going ahead to light the way, he said to his father:

"Follow me and have no fear."

They walked a long distance through the stomach and the whole body of the Shark. When they reached the throat of the monster, they stopped for a while to wait for the right moment in which to make their escape.

I want you to know that the Shark, being very old and suffering from asthma and heart trouble, was obliged to sleep with his mouth open. Because of this, Pinocchio was able to catch a glimpse of the sky filled with stars, as he looked up through the open jaws of his new home.

"The time has come for us to escape," he whispered, turning to his father. "The Shark is fast asleep. The sea is calm and the night is as bright as day. Follow me closely, dear Father, and we shall soon be saved."

No sooner said than done. They climbed up the throat of the monster till they came to that immense open mouth. There they had to walk on tiptoes, for if they tickled the Shark's long tongue he might awaken -- and where would they be then? The tongue was so wide and so long that it looked like a country road. The two fugitives were just about to dive into the sea when the Shark sneezed very suddenly and, as he sneezed, he gave Pinocchio and Geppetto such a jolt that they found themselves thrown on their backs and dashed once more and very unceremoniously into the stomach of the monster.

To make matters worse, the candle went out and father and son were left in the dark.

"And now?" asked Pinocchio with a serious face.

"Now we are lost."

"Why lost? Give me your hand, dear Father, and be careful not to slip!"

"Where will you take me?"

"We must try again. Come with me and don't be afraid."

With these words Pinocchio took his father by the hand and, always walking on tiptoes, they climbed up the monster's throat for a second time. They then crossed the whole tongue and jumped over three rows of teeth. But before they took the last great leap, the Marionette said to his father:

"Climb on my back and hold on tightly to my neck. I'll take care of everything else."

As soon as Geppetto was comfortably seated on his shoulders, Pinocchio, very sure of what he was doing, dived into the water and started to swim. The sea was like oil, the moon shone in all splendor, and the Shark continued to sleep so soundly that not even a cannon shot would have awakened him.

![]()

CHAPTER 36.

Pinocchio finally ceases to be a Marionette and becomes a boy

"My dear Father, we are saved!" cried the Marionette. "All we have to do now is to get to the shore, and that is easy."

Without another word, he swam swiftly away in an effort to reach land as soon as possible. All at once he noticed that Geppetto was shivering and shaking as if with a high fever.

Was he shivering from fear or from cold? Who knows? Perhaps a little of both. But Pinocchio, thinking his father was frightened, tried to comfort him by saying:

"Courage, Father! In a few moments we shall be safe on land."

"But where is that blessed shore?" asked the little old man, more and more worried as he tried to pierce the faraway shadows. "Here I am searching on all sides and I see nothing but sea and sky."

"I see the shore," said the Marionette. "Remember, Father, that I am like a cat. I see better at night than by day."

Poor Pinocchio pretended to be peaceful and contented, but he was far from that. He was beginning to feel discouraged, his strength was leaving him, and his breathing was becoming more and more labored. He felt he could not go on much longer, and the shore was still far away.

He swam a few more strokes. Then he turned to Geppetto and cried out weakly:

"Help me, Father! Help, for I am dying!"

Father and son were really about to drown when they heard a voice like a guitar out of tune call from the sea:

"What is the trouble?"

"It is I and my poor father."

"I know the voice. You are Pinocchio."

"Exactly. And you?"

"I am the Tunny [a tuna fish], your companion in the Shark's stomach."

"And how did you escape?"

"I imitated your example. You are the one who showed me the way and after you went, I followed."

"Tunny, you arrived at the right moment! I implore you, for the love you bear your children, the little Tunnies, to help us, or we are lost!"

"With great pleasure indeed. Hang onto my tail, both of you, and let me lead you. In a twinkling you will be safe on land."

Geppetto and Pinocchio, as you can easily imagine, did not refuse the invitation; indeed, instead of hanging onto the tail, they thought it better to climb on the Tunny's back....

As soon as they reached the shore, Pinocchio was the first to jump to the ground to help his old father. Then he turned to the fish and said to him:

"Dear friend, you have saved my father, and I have not enough words with which to thank you! Allow me to embrace you as a sign of my eternal gratitude."

The Tunny stuck his nose out of the water and Pinocchio knelt on the sand and kissed him most affectionately on his cheek. At this warm greeting, the poor Tunny, who was not used to such tenderness, wept like a child. He felt so embarrassed and ashamed that he turned quickly, plunged into the sea, and disappeared.

In the meantime day had dawned.

Pinocchio offered his arm to Geppetto, who was so weak he could hardly stand, and said to him:

"Lean on my arm, dear Father, and let us go. We will walk very, very slowly, and if we feel tired we can rest by the wayside."

"And where are we going?" asked Geppetto.

"To look for a house or a hut, where they will be kind enough to give us a bite of bread and a bit of straw to sleep on."

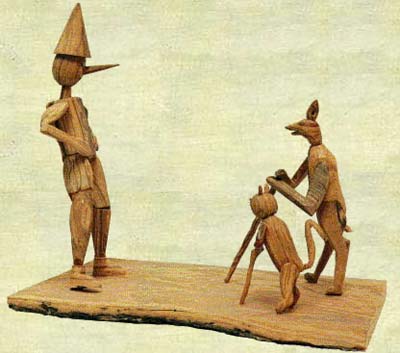

They had not taken a hundred steps when they saw two rough-looking individuals sitting on a stone begging for alms.

|

It was the Fox and the Cat, but one could hardly recognize them, they looked so miserable. The Cat, after pretending to be blind for so many years had really lost the sight of both eyes. And the Fox, old, thin, and almost hairless, had even lost his tail. That sly thief had fallen into deepest poverty, and one day he had been forced to sell his beautiful tail for a bite to eat.

"Oh, Pinocchio," he cried in a tearful voice. "Give us some alms, we beg of you! We are old, tired, and sick."

"Sick!" repeated the Cat.

"Addio, false friends!" answered the Marionette. "You cheated me once, but you will never catch me again."

"Believe us! Today we are truly poor and starving."

"Starving!" repeated the Cat.

"If you are poor; you deserve it! Remember the old proverb which says: 'Stolen money never bears fruit.' Addio, false friends."

"Have mercy on us!"

"On us."

"Addio, false friends. Remember the old proverb which says: 'Bad wheat always makes poor bread!'"

"Do not abandon us."

"Abandon us," repeated the Cat.

"Addio, false friends. Remember the old proverb: 'Whoever steals his neighbor's shirt, usually dies without his own.'"

Waving good-by to them, Pinocchio and Geppetto calmly went on their way. After a few more steps, they saw, at the end of a long road near a clump of trees, a tiny cottage built of straw.

"Someone must live in that little hut," said Pinocchio. "Let us see for ourselves."

They went and knocked at the door.

"Who is it?" said a little voice from within.

"A poor father and a poorer son, without food and with no roof to cover them," answered the Marionette.

"Turn the key and the door will open," said the same little voice.

Pinocchio turned the key and the door opened. As soon as they went in, they looked here and there and everywhere but saw no one.

"Oh -- ho, where is the owner of the hut?" cried Pinocchio, very much surprised.

"Here I am, up here!"

Father and son looked up to the ceiling, and there on a beam sat the Talking Cricket.

"Oh, my dear Cricket," said Pinocchio, bowing politely.

"Oh, now you call me your dear Cricket, but do you remember when you threw your hammer at me to kill me?"

"You are right, dear Cricket. Throw a hammer at me now. I deserve it! But spare my poor old father."

"I am going to spare both the father and the son. I have only wanted to remind you of the trick you long ago played upon me, to teach you that in this world of ours we must be kind and courteous to others, if we want to find kindness and courtesy in our own days of trouble."

"You are right, little Cricket, you are more than right, and I shall remember the lesson you have taught me....?"

...Pinocchio ... made a bed of straw for old Geppetto. He laid him on it and said to the Talking Cricket:

"Tell me, little Cricket, where shall I find a glass of milk for my poor Father?"

"Three fields away from here lives Farmer John. He has some cows. Go there and he will give you what you want."

Pinocchio ran all the way to Farmer John's house. The Farmer said to him:

"How much milk do you want?"

"I want a full glass."

"A full glass costs a penny. First give me the penny."

"I have no penny," answered Pinocchio, sad and ashamed.

"Very bad, my Marionette," answered the Farmer, "very bad. If you have no penny, I have no milk."

"Too bad," said Pinocchio and started to go.

"Wait a moment," said Farmer John. "Perhaps we can come to terms. Do you know how to draw water from a well?"

"I can try."

"Then go to that well you see yonder and draw one hundred bucketfuls of water."

"Very well."

"After you have finished, I shall give you a glass of warm sweet milk."

"I am satisfied."

Farmer John took the Marionette to the well and showed him how to draw the water. Pinocchio set to work as well as he knew how, but long before he had pulled up the one hundred buckets, he was tired out and dripping with perspiration. He had never worked so hard in his life....

The Marionette, ... taking his glass of milk[,] returned to his father.

From that day on, for more than five months, Pinocchio got up every morning just as dawn was breaking and went to the farm to draw water. And every day he was given a glass of warm milk for his poor old father, who grew stronger and better day by day. But he was not satisfied with this. He learned to make baskets of reeds and sold them. With the money he received, he and his father were able to keep from starving.

|

In the evening the Marionette studied by lamplight. With some of the money he had earned, he bought himself a secondhand volume that had a few pages missing, and with that he learned to read in a very short time. As far as writing was concerned, he used a long stick at one end of which he had whittled a long, fine point. Ink he had none, so he used the juice of blackberries or cherries. Little by little his diligence was rewarded. He succeeded, not only in his studies, but also in his work, and a day came when he put enough money together to keep his old father comfortable and happy. Besides this, he was able to save the great amount of fifty pennies. With it he wanted to buy himself a new suit.

One day he said to his father:

"I am going to the market place to buy myself a coat, a cap, and a pair of shoes. When I come back I'll be so dressed up, you will think I am a rich man."

He ran out of the house and up the road to the village, laughing and singing. Suddenly he heard his name called, and looking around to see whence the voice came, he noticed a large snail crawling out of some bushes.

"Don't you recognize me?" said the Snail.

"Yes and no."

"Do you remember the Snail that lived with the Fairy with Azure Hair? Do you not remember how she opened the door for you one night and gave you something to eat?"

"I remember everything," cried Pinocchio. "Answer me quickly, pretty Snail, where have you left my Fairy? What is she doing? Has she forgiven me? Does she remember me? Does she still love me? Is she very far away from here? May I see her?"

At all these questions, tumbling out one after another, the Snail answered, calm as ever:

"My dear Pinocchio, the Fairy is lying ill in a hospital."

"In a hospital?"

"Yes, indeed. She has been stricken with trouble and illness, and she hasn't a penny left with which to buy a bite of bread."

"Really? Oh, how sorry I am! My poor, dear little Fairy! If I had a million I should run to her with it! But I have only fifty pennies. Here they are. I was just going to buy some clothes. Here, take them, little Snail, and give them to my good Fairy."

"What about the new clothes?"

"What does that matter? I should like to sell these rags I have on to help her more. Go, and hurry. Come back here within a couple of days and I hope to have more money for you! Until today I have worked for my father. Now I shall have to work for my mother also. Good-by, and I hope to see you soon."....

When Pinocchio returned home, his father asked him:

"And where is the new suit?"

"I couldn't find one to fit me. I shall have to look again some other day."

That night, Pinocchio, instead of going to bed at ten o'clock waited until midnight, and instead of making eight baskets, he made sixteen.

After that he went to bed and fell asleep. As he slept, he dreamed of his Fairy, beautiful, smiling, and happy, who kissed him and said to him, "Bravo, Pinocchio! In reward for your kind heart, I forgive you for all your old mischief. Boys who love and take good care of their parents when they are old and sick, deserve praise even though they may not be held up as models of obedience and good behavior. Keep on doing so well, and you will be happy."

At that very moment, Pinocchio awoke and opened wide his eyes.

What was his surprise and his joy when, on looking himself over, he saw that he was no longer a Marionette, but that he had become a real live boy! He looked all about him and instead of the usual walls of straw, he found himself in a beautifully furnished little room, the prettiest he had ever seen. In a twinkling, he jumped down from his bed to look on the chair standing near. There, he found a new suit, a new hat, and a pair of shoes.

As soon as he was dressed, he put his hands in his pockets and pulled out a little leather purse on which were written the following words:

The Fairy with Azure Hair returns fifty pennies to her dear Pinocchio with many thanks for his kind heart. |

The Marionette opened the purse to find the money, and behold -- there were fifty gold coins!

Pinocchio ran to the mirror. He hardly recognized himself. The bright face of a tall boy looked at him with wide-awake blue eyes, dark brown hair and happy, smiling lips.

Surrounded by so much splendor, the Marionette hardly knew what he was doing. He rubbed his eyes two or three times, wondering if he were still asleep or awake and decided he must be awake.

"And where is Father?" he cried suddenly. He ran into the next room, and there stood Geppetto, grown years younger overnight, spick and span in his new clothes and gay as a lark in the morning. He was once more Mastro Geppetto, the wood carver, hard at work on a lovely picture frame, decorating it with flowers and leaves, and heads of animals.

"Father, Father, what has happened? Tell me if you can," cried Pinocchio, as he ran and jumped on his Father's neck.... "I wonder where the old Pinocchio of wood has hidden himself?"

"There he is," answered Geppetto. And he pointed to a large Marionette leaning against a chair, head turned to one side, arms hanging limp, and legs twisted under him.

After a long, long look, Pinocchio said to himself with great content:

"How ridiculous I was as a Marionette! And how happy I am, now that I have become a real boy!"

![]()

|