SPRING QUARTER, 2006

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

| Lecture 9. Revolution?

|

|

|

|

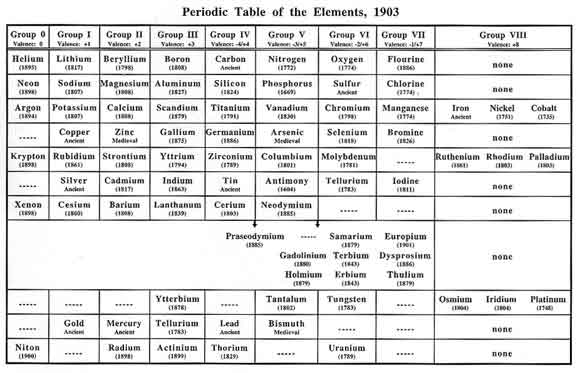

The Elements?

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Things without Soul

Things with Soul

|

|

System of Nature by Carolus Linnaeus (1735) |

|

Animal Kingdom |

|

One-celled animals (Protozoa) Sponges (Porifera) Jellyfish (Coelenterata) Flatworms (Platyhelminthes) Roundworms (Nemathelminthes) Mollusks (Mollusca) Worms (Annelida) Starfish (Echinodermata) Insects (Arthropoda) |

Cartilagenous fish (Elasmobranchii) Bony Fish (Osteichthyes) Amphibians (Amphibia) Reptiles (Reptilia) Birds (Aves) Mammals (Mammalia) |

Plant Kingdom Algae (Thallophytes)

|

|

Celestial Emporium of Benevolent Knowledge,

(????) |

|

All animals are divided into:

|

|

|

|

|

Sowing the Seeds of the Scientific Revolution The middle of the sixteenth century marked the beginning of what some historians of science have called the Scientific Revolution. In their efforts to "rescue" ancient manuscripts from the errors of intervening translation, late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century scholars (humanists) uncovered many irreconcilable differences between the natural world described in ancient and traditional texts and the natural world that presented itself to them through direct observation and fresh reasoning. The books seemed to be saying, "Who are you going to believe? Me? Or your own lyin' eyes?" For a few intrepid souls, the time had come to question these would-be authorities.

Calling this movement a "revolution" conveys the erroneous impression that it happened all at once, or that it was associated with one unifying principle, led by one pivotal figure, and affected all the sciences in the same way. In fact, it was a gradual intellectual shift over at least two centuries, participated in by a wide range of individuals, each one following a slightly different path in search of the truth. To see examples of the variety of methods used and conclusions reached by investigators in this period, review these works from Week 3 and 4's readings:

|

Can you identify passages that reflect the author's adherence to the mystical, organic, and/or mechanical intellectual tradition? Does one of these traditions form the principal, or even sole, basis on which the author draws his conclusions? How do their investigative aims and methods compare with those of their predecessors (Aristotle, Albertus Magnus, Paracelsus...)? |

|