SPRING QUARTER, 2006

Department of History

University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Week 8. Behavior The Evolution of Life: Professor Huxley's Address at Liverpool (1870)

|

appeared in Nature October 20, 1870

LETTERS TO THE EDITOR

[The Editor does not hold himself responsible for opinions expressed by his Correspondents. No notice is taken of anonymous communications.]

BELIEVING that readers of NATURE can feel no interest in the extended personalities with which Prof. Huxley almost fills his letter this week, and believing also that such matters are little worthy of occupying your columns, I shall only allude to that part of his letter which contains statements having a scientific bearing.

The distinct issue raised in my experiments was, were living things to be found in the fluids of my flasks? If so, such living things must either have braved a higher degree of heat than had been hitherto thought possible, or else they had been evolved de novo.

The effect of the very high temperature upon pre-existing living things, which were purposely exposed thereto, was shown by their complete disorganisation in an experiment which is recorded in NATURE, No. 37, p. 219, and to this I would especially direct Prof. Huxley's attention.

|

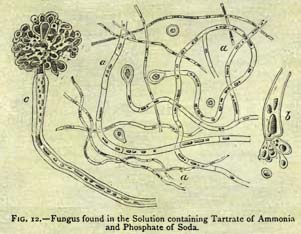

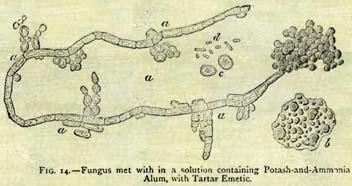

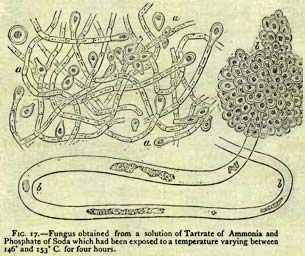

Prof. Huxley advances an explanation of the mode of origin of the distinct fungi, bearing masses of fructification (NATURE, No. 36, figs. 12, 14, and 17) found in my flasks after exposure to temperatures at and beyond Pasteur's standard of destructive heat; his theory is entirely novel, apparently extemporised for the occasion and is very startling. He says, and in justice to Prof. Huxley I quote the passage in full,

"Any time these six months Dr. Bastian has known perfectly well that I believe that the organisms which he got out of his tubes are exactly those which he has put into them; that I believe that he has used impure materials, and that what he imagines to have been the gradual development of life and organisation in his solutions is the very simple result of the setting together of the solid impurities, which he was not sufficiently careful to see when in their scattered condition when the solutions were made."

Now, although it was quite true that minute portions of Sphagnum leaf were found in two unpublished experiments, it seems very marvellous that on this slender foundation Prof. Huxley should hazard such a purely imaginative and unprecedented hypothesis as to the mode of production of fungi.

I have, moreover, not been able to see why the occurrence of the incident to which he refers should make him repudiate a number of experiments in which unmistakeably living things were found in fluids from hermetically sealed flasks after these and their contents had been exposed to temperatures higher than those which living things are known to be capable of resisting.

Following a precept more honoured in dialectics than in science, Prof. Huxley has attacked his opponent rather than the arguments which he affects to destroy. He objects to only one passage in my "Reply," and this he thinks was not worthy of the special type in which it was printed; and yet, notwithstanding its special type, I can only conclude from his reply that Prof. Huxley has failed to appreciate its meaning. My words were: Living things may and do arise as minutest visible specks, in solutions in which, but a few hours before, no such specks were to be seen." The word which now alone stands in italics was ignored by Prof. Huxley. I had no wish to tell him that certain refractive particles, or foreign bodies, might not be visible in the thin film of fluid to which I referred. I alluded to the gradual and equable development of living specks throughout a fluid containing no apparent germs. His retort that some unobserved visible germs might have become centres of development is a contre-sens. It does not apply to the gradual appearance of myriads of equally diffused motionless particles in a motionless film of fluid.

The very authoritative tone which Prof. Huxley has lately assumed in his remarks concerning Brownian movements and those of living organisms, fails to impress me very much. His knowledge about these movements, as I have good reason to know, is of quite recent growth. Movements which, in the month of March of the present year, Prof. Huxley did not regard as Brownian, he now does believe to have been of this nature. If he is now right, what value is to be set upon his knowledge of Brownian movements six months ago; and what guarantee have we that in another six months Prof. Huxley may not again take a different view?

Let me assure Prof. Huxley, however, that the duty which he is "credibly informed" he owes to the public remains still undischarged. I protested against his "Address" on scientific grounds which are fully stated, and those who have read my protest will see that Prof. Huxley cannot dispose of the question really at issue by recounting any mistakes of mine, whether real or imaginary. If, as I believe, he has failed to give any worthy or serious view of the question, this could have been in no way necessitated by a disbelief, however strong, in my experiments. The labours of Profs. Wyman, Mantegazza, and Cantoni had already taken the question into regions never attained by M. Pasteur, and therefore they demanded a fair consideration. Is Prof. Huxley, in his capacity of President of the British Association, warranted in ignoring their labours, and therefore in misrepresenting the present state of science on the subject, because, owing to two errors among my many experiments, he declares himself to have altogether lost faith in my skill or capacity as an investigator? The answer cannot be doubtful. Is it, again, consistent with his high responsibilities that he should pervert the real issues, and should do a grave injustice to others, in order that he might preserve a "silence" which should be his "best kindness" to me? Let me tell Prof. Huxley that I repudiate such "kindness," as any honest man would who is simply seeking after truth, and relegate it to the same regions as I would that indescribable air of restrained omniscience whereby he endeavours to crush arguments and facts, to which he altogether fails to reply.

H. Charlton Bastian

University College, Oct. 17

![]()

|