University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Lecture 19. Finding the "1 big 1"

|

|

|

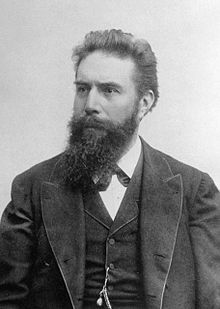

| Wilhelm

Roentgen (1845-1923)

November 1895 When electricity

flows through a vacuum tube, penetrating invisible radiation is emitted. |

|

Shadowgraph of Frau Roentgen's hand created by "x-rays"-- December 22, 1895. |

|

|

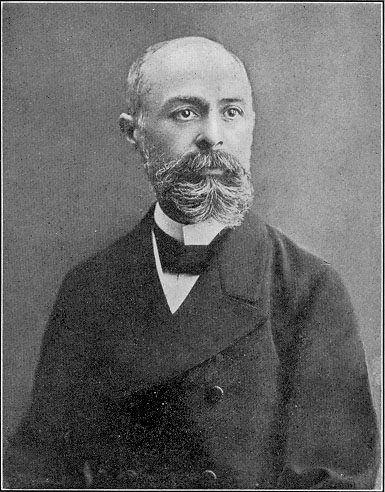

Henri Becquerel (1852-1908)

February 1896 Uranium salts spontaneously emit invisible rays that are similar to x-rays, although not as penetrating. |

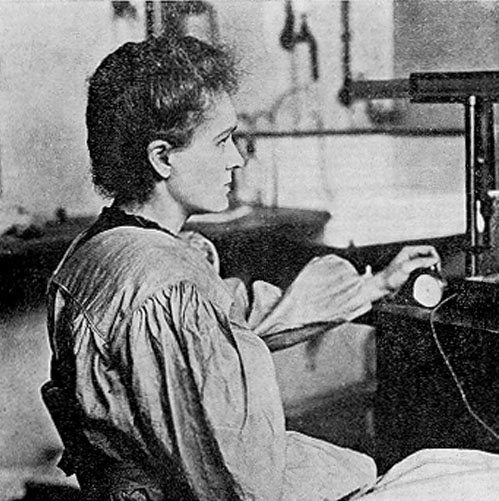

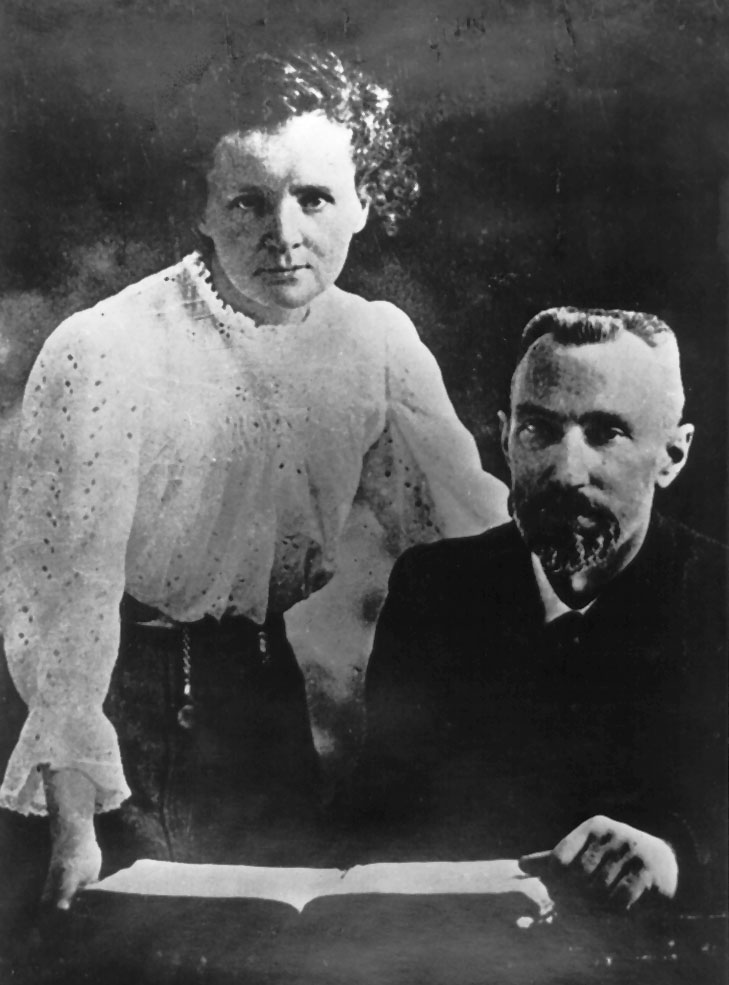

| Marie Sklodovska Curie (1867-1934)

February 1898 Uranium is not the only natural emitter of penetrating radiation. "Radioactivity," like magnetism, is a property possessed by a select group of elements. |

|

|

December 1898 Pitchblende, a uranium ore, is more radioactive than pure uranium!! Curie isolated a new element in the pitchblende, polonium, and another, even more potent source of radioactivity: radium. |

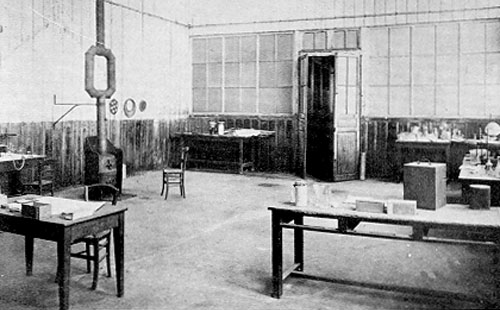

| Marie at work with

Pierre Curie (1859-1906) 1902 The Curies isolated radium and determined it to be another new element.

1903 They shared the Nobel Physics Prize with Henri Becquerel. |

|

|

______________ January 14,1904 ...Dr. Morton explained in detail the uses to which radium might be put in curing diseases, particularly those of an internal nature. "Medicine," he said, "is gradually abandoning its old-fashioned concoctions, and we are taking up radium with exceedingly bright prospects. Its use will consist of physical treatment almost exclusively. The Roentgen ray has been of immense value in curing cancer, but radium promises to go far ahead of it. If we had radium of 150,000 activity we could no doubt do a great deal more than we are doing now. Most of us have been confined to a much lower radio-activity. We have been working with from 7,000 to 10,000 luminosity.... "The advantage of radium over the X ray is that it can be applied direct to the part affected. For example, if placed in a small tube it may be inserted in the throat, and in similar manner it may be applied to any vital region. In other words, with radium we shall be able to get at the seat of diseases. There is no end, in my opinion, to the cures which may be effected by radio-activity, excited in one way or another."... |

|

|

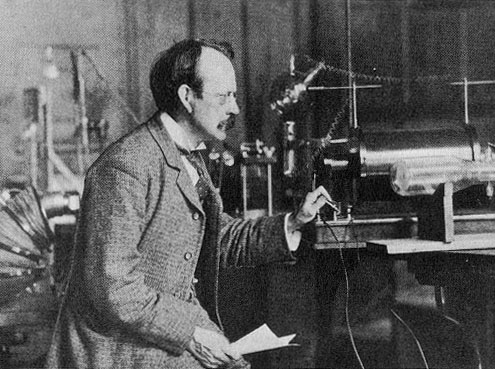

Joseph John Thomson (1856-1940)

1899 |

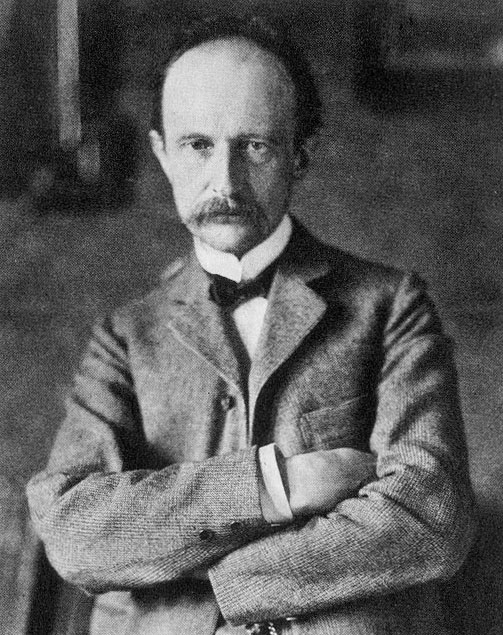

| Max Planck (1857-1947) 1900 Some phenomena can be more readily explained if light energy is treated as though it were broken down into tiny little packages: quanta. "My futile attempts to fit the ... quantum ... somehow into the classical theory continued for a number of years, and they cost me a great deal of effort." |

|

|

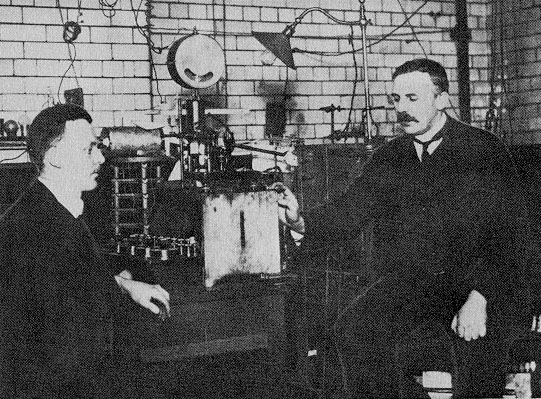

Hans Geiger (1882-1945) and Ernest Rutherford 1911 Atoms have small, massive positively charged nuclei. |

|

|

||

| 1934 | Irène Joliot-Curie (1897-1956) and Frédéric Joliot (1900-1958) found that it is possible to induce radioactivity in normally stable elements. Bombarding aluminum (atomic number = 13) with alpha particles (helium nuclei, comprised of 2 protons and 2 neutrons) caused some of the aluminum nuclei to capture an alpha particle. Now unstable, these nuclei immediately emitted a neutron, thus producing a new element--a radioactive isotope of phosphorus (at. no. = 15). One no longer had to rely solely on natural materials for sources of radioactivity--radioactive elements could be manufactured in the laboratory. Perhaps their rate of radioactive emission could be controlled! |

| 1938 | Otto Hahn (1879-1968) and Fritz Strassmann (1902-1980) announced the surprising observation that bombarding uranium (at. no. = 92) with neutrons did not produce radium atoms (at. no. = 88) as expected. Instead, the product was an element with a considerably lower atomic number--barium (at. no. = 56). Hahn and Strassman suspected that the uranium nuclei were being broken into two nearly equal parts, a process they called "fission". |

| 1939 | Niels Bohr (1885-1962) announced results of an experiment by Lise Meitner (1878-1968) and Otto Frisch (1904-1979) which confirmed Hahn and Strassman's discovery. |

|

2 August 1939 Some recent work by E. Fermi and L. Szilard, which has been communicated to me in manuscript, leads me to expect that the element uranium may be turned into a new and important source of energy in the immediate future.... In the course of the last four months [research has shown] that it may become possible to set up a nuclear chain reaction in a large mass of uranium, by which vast amounts of power and large quantities of new radium-like elements would be generated. Now it appears almost certain that this could be achieved in the immediate future. This new phenomenon would also lead to the construction of bombs, and it is conceivable--though much less certain--that extremely powerful bombs of a new type may thus be constructed. A single bomb of this type ... might very well destroy [a] whole port together with some of the surrounding territory.... |

|

| 1939 | FDR formed an ad hoc committee on uranium |

| 1940 | National Defense Research Committee established to mobilize atomic research |

| 1941 | Otto Frisch and Rudolf Peierls (1907-1995) calculate that a small amount

of fissionable uranium can produce an explosion equal to several thousand

tons of TNT

National Academy of Science urges all-out effort to build atomic weapons US enters World War II |

| 1942 | research program reorganized and given over to the War Department;

code name: Manhattan Engineer District

research conference held in summer at UC Berkeley to work out theoretical details of nuclear weapon Robert Oppenheimer named director of Manhattan Engineer District Los Alamos, New Mexico selected as research site for project team working under Enrico Fermi at the University of Chicago produce first controlled chain reaction |

| 1943 | nuclear reactors begin production of sufficient fissionable material

for atomic weapon

research begins at Los Alamos on creation of "the gadget" experiments begin when first plutonium arrives at Los Alamos |

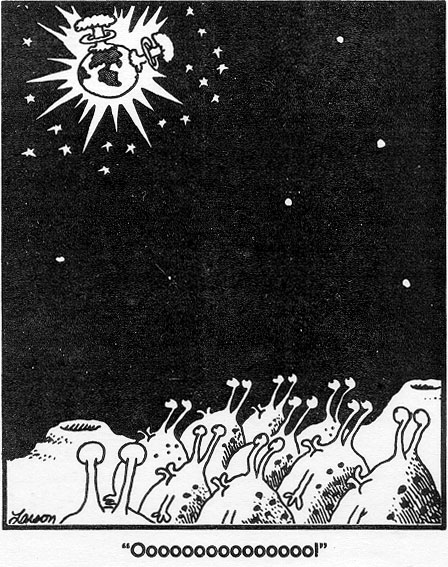

| 1945 | April 12 -- cerebral hemorrhage causes the death of FDR; vice-president Harry S Truman sworn in as president

May 8 -- VE day July 16 -- test of "the gadget" in the Jornado del Muerto desert in New Mexico August 7--uranium weapon dropped on Hiroshima August 9--plutonium weapon dropped on Nagasaki August 15--VJ day |

| 1951 | physicist Max Born pondered the implications of the weapon's use:

It seems to me that the scientists who led the way to the atomic bomb were extremely skillful and ingenious, but not wise men. They delivered the fruits of their discoveries unconditionally into the hands of politicians and soldiers; thus they lost their moral innocence and their intellectual freedom.... |

March 1, 1954

"Bravo" -- thermonuclear bomb test over the Bikini

Atoll.

|

|

____________ March 1, 2004 COMMENTARY

From a Tropical Paradise to a Nuclear Hell Fifty years ago today, Bikini Atoll was blasted away.

The pain from bomb testing rages on in the Marshall Islands.

By JoAnn Wypijewski JoAnn Wypijewski has written on Pacific issues since the 1980s for the Nation, the Los Angeles Times and Harper's. "There's a story I can tell you," a fellow called Bruno Lat said to me a few years back. "I was 13. My dad was working with the Navy as a laborer on Kwajalein"--an atoll in Lat's native Marshall Islands, controlled by the U.S. military. "It was early, early morning. We were all outside on that day waiting in the dark. Everybody was waiting for the Bravo." That day was 50 years ago: March 1, 1954. Bravo was not the first, or the last, just the worst of the American nuclear tests in the Pacific--a fission-fusion-fission reaction, a thermonuclear explosion, an H-bomb, the United States' biggest blast. In today's poverty of expression, it would be called a WMD. Except that it was ours, and so real that days after marveling at a sky alight with "all kinds of beautiful colors," young Bruno also took in the sight of refugees from downwind of the blast at Bikini Atoll, miserable and burned and belatedly evacuated to Kwajalein. The skin on their heads, he recalled, "you could peel it like fried chicken skin." In the standard histories, much of what happened that morning was "an accident." That's the term Edward Teller, the bomb's designer, uses in his memoir. The Navy said it had anticipated a six-megaton bomb, but Bravo came in at 15. It expected the winds to blow one way; they blew another. It had not evacuated downwinders in advance because the danger was deemed slight, and anyway the budget was tight. It had not expected that a Japanese fishing boat, the Lucky Dragon, would be trawling 87 miles from the blast. It had not expected that one of the fishermen would die. Officially, the Atomic Energy Commission claimed that the Bravo shot had been "routine" and that among the evacuees "there were no burns. All were reported well." A month later, AEC Chairman Lewis Strauss told reporters that they were not only well but "happy" too. It is a simple matter to find government reports acknowledging the opposite now that that particular lie is unnecessary. The Bravo blast, it is typically said, was equal to 1,000 Hiroshimas, as if that were comprehensible. The Hiroshima bomb instantly killed 80,000 people, more or less. Bravo had the power to incinerate 80 million: 10 New Yorks; 26,666 Twin Towers, more or less. The "stem" of its mushroom cloud was 18 miles tall, its "cap" 62 miles across. That's a cloud five times the length of Manhattan, vaporizing all beneath it, sucking everything--in Bravo's case, three islands' worth of coral reef, sand, land and sea life--into the sky, and then showering it in a swirl of radioactive isotopes across an area now estimated at nearly 20,000 square miles.

Map showing the islands affected by the "Bravo" test. The Marshallese on the island of Rongelap, 120 miles from ground zero, had imagined snow from missionaries' photographs of New England winters. That March 1, they imagined the white flakes falling from the sky, piling up two inches deep, as some freakish snowstorm. Children played in it, and later screamed with pain. On other downwind islands, the "snow" appeared variably as a shower, a mist, a fog. The Navy had a practice of sending planes into a blast area hours after detonation to measure the "geigers," as radioactivity was colloquially known among sailors, and the early Bravo readings are staggering. Scientists didn't know in 1954 that, for example, a radiation dose of 30 roentgens would double the rate of breast cancer in adults. But they did know that 150 roentgens, noted in one of the military's earliest ground-level estimates of Rongelap, was catastrophic. Yet the Navy waited two days to evacuate Rongelap and Ailinginae; three days to evacuate Utirik. Nine years later, thyroid cancers started appearing in exposed islanders, then leukemia. Even on "safe" atolls, babies began being born retarded, deformed, stillborn or worse. In 1983, Darlene Keju-Johnson, a Marshallese public health worker, gave a World Council of Churches gathering this description: "The baby is born on the labor table, and it breathes and moves up and down, but it is not shaped like a human being. It looks like a bag of jelly." The Marshallese say that Bravo was not an accident. In the 1980s, a U.S. government document surfaced showing that weather reports hours before the blast had indeed indicated shifting winds. In 1954, the United States had nine years of data on direct effects of radiation but none on fallout downwind; select Marshallese have been the subject of scientific study ever since. An accident, as the writer Alexander Cockburn once put it, "is normalcy raised to the level of drama." Marshall Islanders endured 67 U.S. nuclear tests between 1946 and 1958, their net yield the equivalent of 1.7 Hiroshima bombs detonated every day for 12 years. A full accounting of the displacements and evacuations, the lies and broken promises would fill pages. A full accounting of the health effect would fill volumes and has never been done. Bruno Lat is not an official victim of any test, so his thyroid cancer doesn't count; the same with his father's stomach tumors. Of the broken culture and broken hearts, there can be no accounting. Today what's left of Bikini Atoll is beautiful, its white sands shimmering beneath the dome of blue, its coconut crabs skittering among the palms, but what grows there is poison. It is not difficult in the Marshall Islands to find people who have forever lost their home, who believe that sickness awaits, that nothing is safe, but we don't call that terror. On this 50th anniversary of Bravo, the Marshallese are petitioning the U.S. Congress to make full compensation for the ruin of their lands and their health. They want Congress to express "deep regret for the nuclear testing legacy." Some had wanted an apology, but that, the majority decided, the United States would never concede. |

|

________________ September 10, 2003 Edward Teller, 'Father of the Hydrogen Bomb,' is dead at 95 BY JOEL N. SHURKIN

Edward Teller, one of the most controversial scientists of the 20th century because of his role as the developer of the hydrogen bomb and his outspoken support for an unassailable nuclear arsenal, died Sept. 9 in his home on the Stanford campus. A senior fellow at the Hoover Institution at Stanford, he was 95. He served as director of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, a major weapons research facility built largely for him. Teller was at Einstein's side when the physicist signed the famous letter to Franklin Roosevelt urging the construction of an atomic bomb that led indirectly to the Manhattan Project. Along with Stanislaw Ulam, Teller designed the first hydrogen bomb. Teller also was influential in the decision by the Truman administration to produce the bomb over the objections of much of the scientific community. His testimony against physicist J. Robert Oppenheimer, the fallout of the H-bomb dispute, made Teller a pariah to many of his colleagues, further diverting his career from science to defense politics, and causing him profound sorrow. Some old associates refused to speak to him for more than 30 years. "If a person leaves his country, leaves his continent, leaves his relatives, leaves his friends," Teller said, "the only people he knows are his professional colleagues. If more than 90 percent of these men then come around to consider him an enemy, an outcast, it is bound to have an effect. The truth is it had a profound effect. It affected me, it affected [his late wife] Mici, it even affected her health." The model for the title character of Stanley Kubrick's satirical film Dr. Strangelove, Teller became in the last half of his life the leading proponent of major weapons systems, the guiding inspiration for the Strategic Defense Initiative ("Star Wars") and an enthusiastic supporter of nuclear energy. He became arguably the most influential scientist of the Reagan Administration. "If I am proud of anything," he told an interviewer, "it is that I got a second lab [Livermore] started and established with relatively little help, and a second weapons system [the hydrogen bomb] that we desperately needed then. Livermore is still the place where the new ideas, these new defensive weapons, will continue to come from." Math at an early age Teller was born in Budapest on Jan. 15, 1908. The son of a lawyer, he belonged to an astonishing generation of Hungarian Jews who grew up in Budapest, in many cases went to the same school, and which produced seven of the 20th century's most influential physicists and mathematicians. They included, besides Teller, the mathematician John von Neumann; physicists Eugene Wigner and Leo Szilard; and the engineer Theodor von Kármán. Wigner, Szilard and von Neumann worked with Teller on the atomic bomb, and their colleagues would smilingly refer to them as "the Hungarian conspiracy." At an early age, Teller said, he learned the fun of mathematics. He would stay awake in bed working out mathematical problems such as computing the number of seconds in a day. His father was unhappy when Teller announced he wanted to be a mathematician. "My father said I couldn't make a living that way, so we compromised, a little painfully, on chemistry. But I cheated. I studied chemistry and mathematics. After two years, my father gave up and told me to study what I wanted," he recalled. It was still a time when mathematics and physics were considered one field, and the place to study it was in Germany, so Teller left Budapest for Karlsruhe Technical Institute and the University of Munich. (It was at Munich that Teller lost a foot in a trolley car accident. He wore a prosthesis the rest of his life, leaving him with a slight limp.) He received his Ph.D. at the age of 22 from the University of Leipzig in 1930, writing his dissertation under Werner Heisenberg, the developer of the Uncertainty Principle, who would later work on Hitler's atomic bomb project. Teller went on to Göttingen, then the physics and mathematics polestar of the world, to work on the molecular structure of matter, but, like most of his colleagues, he finally was forced to flee Germany with the rise of the Nazis. He emigrated to the United States in 1938, taking a position at George Washington University, and collaborated with George Gamow in a study on radiation, which made a major contribution to solid-state physics. "His work is illuminated by deep physical insight of the kind that belongs in the great school of physics," physicist John Wheeler of the University of Texas once remarked. By the late 1930s, physicists in Germany, France, Britain and the United States were edging toward the ability to split atoms and release the huge energy stored therein, following Einstein's E=mc². The great fear among the non-German scientists was that Germany, working under Heisenberg, would be the first to succeed in harnessing this explosive power for a weapon. Led by Szilard, the scientific community began to see the need for further research and tried to get the British and American governments interested. Szilard wanted to enlist Einstein, then the most famous scientist in the world, to get Washington's attention. In the summer of 1939, Szilard decided to visit Einstein at his summer home on Long Island. Because he could not drive a car, he asked Teller to drive him up. "It was a little difficult to find Einstein," Teller wrote later. "Several inquiries failed to elicit the whereabouts of this obscure personage. In the end we asked a young girl not yet 10 years of age, with two fairly long braids, who responded positively to an inquiry about a nice old gentleman with plenty of white hair." Einstein served tea and then signed the letter Szilard had prepared. Contrary to folklore, Roosevelt probably never read the letter, but did listen to the economist Alexander Sachs, who brought the letter from Einstein and summarized it for him. Thus began the steps that led to Los Alamos. Teller joked that he began his career in atomic physics as Szilard's chauffeur. The Manhattan Project Teller was one of the first to arrive at Los Alamos in April of 1943, helping Oppenheimer recruit and organize the Manhattan Project. He and his wife, Mici, brought his pride and joy, a 100-year-old Steinway piano, on which Teller boomed out Bach and Mozart, to the distraction of his neighbors. He was 35 years old. Most of those who knew him remarked about his huge forest of eyebrows, and the intense, riveting eyes beneath them. Ulam described him as "always intense, visibly ambitious, and harboring a smoldering passion for achievement in physics. He was a warm person and clearly desired friendship with other physicists." His relationship with Oppenheimer was complex, with Teller praising him initially for his ability to organize what turned out to be the greatest collection of scientific talent in the history of the world into a productive team despite all the restrictions of secrecy and military interference with the process. But gradually, the two men grew cooler. Friends said Teller resented Oppenheimer's charismatic hold on their colleagues, especially since Teller was convinced--and many agreed with him--that he was the better physicist. Relations got cooler when Oppenheimer named Hans Bethe as director of the theoretical division, a position Teller coveted. Bethe and Teller clashed repeatedly, and Oppenheimer had to play referee. More important, all but Teller had agreed that the project would narrow its scope toward the construction of a fission bomb. Teller decided that they should go well beyond that toward a thermonuclear device, a fusion bomb. His constant attempts to get support for the "Super," as he called it, were seen by many, including Oppenheimer, as a distraction. He became even more of a distraction when he produced equations that showed the possibility that a fission weapon could ignite the world's atmosphere. It was later discovered his calculations were wrong--and a dozen other men made similar mistakes later--but work stopped until the flaw was found. On July 16, 1945, the atomic bomb was tested at Trinity Site, near Alamagordo, N.M. "I was looking, contrary to regulations, straight at the bomb," Teller said. "I put on welding glasses, suntan lotion, and gloves. I looked the beast in the eye, and I was impressed." So were the others at Los Alamos. With the war in Europe obviously over (the Germans never came close to producing a bomb), the only enemy left was the Japanese. Many of the scientists behind the bomb project were Jewish refugees from Hitler, and while they saw Japan as the enemy of their adopted country, they did not have the same moral outrage against Japan as they did against Nazi Germany. Some also worried about the morality of dropping the atomic bomb on a civilian target without warning. Szilard proposed a petition at Los Alamos opposing the looming attack. For years Teller maintained that he opposed use of the bomb on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and that he only refused to sign the petition at Oppenheimer's behest. In fact, according to Stanford history Professor Barton Bernstein, Teller did not oppose Hiroshima. In a July 2, 1945 letter to Szilard, Teller wrote: "If you should succeed in convincing me that your moral objections are valid, I should quit working. I hardly think that I would start protesting." He said actual use of the atomic bomb in combat "might even be the best thing, [for it] might help to convince everybody that the next war would be fatal." After the war was over, Teller went to work with Enrico Fermi in Chicago, convinced the atomic bomb alone would not guarantee peace. He continued to push for development of the Super. But a 1949 committee of scientists, led by Oppenheimer, declared the Super both unnecessary and immoral. To Teller, this was dangerous advice. With the Cold War pulsing about them, Truman, at Teller's urging, overruled the scientific committee and went ahead with development of the fusion bomb. Teller contributed still-secret work on the design. But even here, his contributions, perhaps discolored by the subsequent controversy, are not clear. He is generally credited with much of the design work. Bethe maintained that Teller's miscalculations at Los Alamos actually delayed development of the Super. "Nobody will blame Teller because the calculations of 1946 were wrong, especially because adequate computing machines were not then available. But he was blamed at Los Alamos for leading the laboratory, and indeed the whole country, into an adventurous program on the basis of calculations which he himself must have known to have been very incomplete." "Nine out of 10 of Teller's ideas are useless," Bethe wrote. Teller "needs men with more judgment, even if they are less gifted, to select the 10th idea, which is often a stroke of genius." The first thermonuclear device was exploded in November, 1952. By this time, Oppenheimer was director of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton and still was exerting great influence over the scientific establishment. In December 1953, Oppenheimer's security clearance was suspended by a special panel formed by the Atomic Energy Commission to decide if he was a security risk. The formal charges were based partly on Teller's secret interview in 1952 with the FBI. Oppenheimer had a seriously problematic security file. His wife, brother, sister-in-law and a former lover were Communists, and he supported and belonged to a number of Communist front organizations in Berkeley in the 1930s. But most of the scientists called to testify supported Oppenheimer, disputing the validity of the charge he was then a security risk. Teller was one of the few exceptions. At the end of his generally complimentary testimony, Teller was asked if he considered Oppenheimer a security risk. He responded with 24 words that triggered one of the most bitter feuds in the history of American science: "I feel that I would like to see the vital interests of this country in hands which I understand better, and therefore trust more." He claims he only meant that Oppenheimer was a complex character and that he did not fully understand him (in which he was hardly alone), but the effect was explosive. When he was done, he walked by Oppenheimer and said, "I'm sorry. "After what you've just said, I don't understand what you mean," Oppenheimer replied and turned away. Oppenheimer lost his security clearance and retired back to Princeton in disgrace. With those words, Teller changed his life. Less than a week later, he was visiting Los Alamos when he ran into physicist Robert Christie, a long-time colleague. Teller put out his hand to shake Christie's. Christie looked down at the hand, spun on his heels, and without a word, walked away. Teller and his wife immediately left the dining room and returned to their hotel. Teller told an interviewer he broke down and wept. Decades in 'exile' He found he had exiled himself from the mainstream of the physics community, an exile that lasted the rest of his life. In later years, Oppenheimer would take on the status of a folk hero to scientists, Teller the vengeful caitiff who destroyed him. Teller claimed his actions in the Oppenheimer matter were passive, limited only to his testimony, but he had actually helped begin the process. He later admitted to physicist-historian Daniel Kevles and Bernstein that he was convinced Oppenheimer was a Communist whose name was being hidden by the Party. "I do not look at Oppenheimer as a villain," Teller once said, "and I most certainly do not look at him as an object of admiration. I will say that I blame Oppenheimer's disciples for much more than I blame him." When Oppenheimer received the Fermi Prize from President Johnson, Teller was there to shake his hand in front of cameras. He moved from Chicago to Los Alamos as assistant director, to consult on the creation of Livermore and serve as professor of physics at the University of California-Berkeley. He held several positions in the University of California system, including university professor and professor emeritus, and at Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, which is run under contract by Cal. He served as director from 1958 to 1960, and as associate director from 1960 to 1975. While he published scientific research papers until the early 1950s, he concentrated the rest of his life on matters of war and peace, and his belief that security lay in an unassailable offensive and defensive posture. He said he regretted leaving active physics but felt a moral imperative in working toward strong national armaments for defense. "I cannot just go back to physics because I believe that to prevent another war happens to be incomparably more important," he said. The military establishment found him an ardent supporter in the scientific community, backing most major weapons systems. He opposed the SALT talks on grounds that the Soviets simply could not be trusted, and the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty in 1972. He supported Safeguard, an anti-missile system designed to protect U.S. weapons from Soviet attack. He sternly opposed the nuclear freeze movement. "Nuclear war is for me a real possibility and has been for the last 40 years," he told an interviewer for Forbes magazine in 1980. "If we went into a nuclear war today, there is practically no question that the Russians would win that war and the United States would not exist." "For a quarter of a century we have conceived of our situation as a balance of terror, and the dreadful point is, that the terror is obvious; the balance is not," he said in a speech to the National Press Club in 1982. Nuclear weaponry, he told a San Jose Mercury News reporter, "is not an obsession; it's my duty.... I'm doing it because few others are doing it, and it's the route away from either Soviet world domination or destruction." He opposed secrecy in developing the weapons, frequently quoting the Danish physicist Niels Bohr: "In the Cold War, it would be reasonable to expect that each side will use the weapons that it can use best. And the appropriate weapon for a dictatorship is secrecy. But the appropriate weapon for a democracy is the weapon of openness." He said too many people know the secrets of the hydrogen bomb for it to remain much of a secret, although he wouldn't favor sending the Soviets the blueprints. Teller lamented that the Soviet Union was prepared for a possible war with an extensive civil defense infrastructure, while the United States was not. His influence on politicians in the 1950s, particularly Nelson Rockefeller, led to many of the civil defense procedures, including shelters, developed then. He believed a nuclear war, as calamitous as it would be, could be won. His positions won him back none of the friends he lost in the Oppenheimer affair. Nobelist I.I. Rabi once said that Teller was "a danger to all that's important." Teller favored plans to use nuclear explosions for peaceful purposes, such as digging canals, and frequently derided critics who claimed that even the lowest-level radiation from such explosions was dangerous. In the 1970s, he crusaded for nuclear power and suffered a heart attack after Three Mile Island. He later appeared in a full-page advertisement in the Wall Street Journal blaming his coronary on Jane Fonda and other critics of the nuclear industry. The ad was paid for by the company that produced the valve that stuck in the plant. His belief in marching science and technology into the service of national defense led to his strong support for the Strategic Defense Initiative, particularly in the development of laser weapons. Teller is generally credited with convincing President Reagan of the efficacy of "Star Wars." Even that, of course, led to controversy, with a number of scientists, including some at Livermore where most of the work was done, charging that Teller fudged his data to convince the politicians. Teller and his supporters at Livermore and the Defense Department strongly denied the charges. He spent considerable amounts of time lecturing and debating "Star Wars" and his defense positions in his later years. Many of the debates were with physicists at Stanford and the Stanford Linear Accelerator Center (SLAC). His frequent position was that he knew more than they about weapons technology, a point they refused to give. "If you knew what I know, you'd agree with me," he once said in a debate with then-SLAC director Wolfgang Panofsky. "I do know what he knows and I don't agree with him," retorted Panofsky. "I think that extremism may not be the most deadly of sins," Teller admitted once, "but the most widespread, and occasionally, I trap myself in it." Friends said he harbored some bitterness that he never won a Nobel Prize for his early work in physics, which even his critics admit was brilliant and innovative. He blamed politics and the fact he was known as the "father of the hydrogen bomb." His protégé, Lowell Wood at Livermore, said that if it were not for the bomb "chances are two to three he'd get the Nobel Prize. He's commented to me that if he reared up on his hind legs and denounced the U.S. government, he'd be a good candidate." But his critics could not let even that go by unchallenged. Marvin Goldberger, who had been a student of Teller's, Caltech president and twice-removed successor to Oppenheimer at the Institute for Advanced Study, once called him a "very good physicist, extraordinarily imaginative, creative person. He was about as close to the Nobel Prize as our cat." Teller traveled extensively, even after a triple bypass operation, and was constantly in demand as a speaker, the scientific voice of the military establishment. He taught Hebrew school in his later years in a local synagogue, and spent as much time at his beloved piano as he could. Still, his exile from his colleagues and friends, which he felt was the price of speaking his conscience, left a deep melancholy. "I am not a loner," he told a Discover magazine reporter. "I like to work with others. I have friends among physicists today, outside of Livermore as well, but not very many. And those I do have I don't see very often. "You know, an intellectual is not necessarily a man who is intelligent, but someone who agrees with other intellectuals. He is a man with whom it is acceptable for other intellectuals to associate. I lost my membership card in the club." Teller won numerous awards, including the Fermi Prize, the National Medal of Science and, in July, the Presidential Medal of Freedom. He was a member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the National Academy of Science; a fellow of the American Physical Society and the American Nuclear Society; and a member of the scientific advisory boards of the U.S. Air Force and various businesses. He published more than a dozen books on subjects ranging from energy policy and defense issues to his own memoirs. Teller is survived by his son Paul, daughter Wendy, four grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Joel N. Shurkin is a former science writer for the Stanford News Service. |

|

Is technical knowledge inherently dangerous?

Can we learn to distinguish between wisdom and cleverness?

|