University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Lecture 17. Perfecting Worlds

|

|

|

If you can engineer machines, what about society? If Frederick Winslow Taylor is correct and individual's behavior can be regulated, or made machine-like, what about whole collections of individuals? Utopias and dystopias are forms of prophetic history rooted in modes of thought and perception of the age in which they were written. Utopian narratives often contrast idyllic visionary futures with the more sordid present, but they seldom offer a persuasively detailed explanation of how such a social ideal might be realized. By contrast, dystopian narratives, like Riddley Walker, are usually intended to serve as moral tales of how the worst angels of our nature can and will shape humanity's future unless we take the reins and guide the world toward a more positive outcome. |

|

Eden

Genesis 1-3 Population: 2

|

|

Republic (c. 370 BC)

Population: 5,040

|

|

Utopia (1516) -- word "Utopia" derived from Greek meaning "Nowhere"

Population: 54 cities, each with 100,000 inhabitants.

|

|

Abbey of Thélème (1534) described in Gargantua

|

|

|

Christianopolis (1618)

|

|

Salomon's House (1627), described in New Atlantis

"The end [goal] of our foundation is the knowledge of causes, and secret motions of things; and the enlarging of the bounds of human empire, to the effecting of all things possible. The Resources at Saloman's House "The preparations and instruments are these: We have large and deep caves of several depths; the deepest are sunk 600 fathoms; and some of them are digged and made under great hills and mountains; so that if you reckon together the depth of the hill and the depth of the cave, they are, some of them, above three miles deep.... We use them likewise for the imitation of natural mines and the producing also of new artificial metals, by compositions and materials which we use and lay there for many years. We use them also sometimes (which may seem strange) for curing of some diseases, and for prolongation of life, in some hermits that choose to live there, well accommodated of all things necessary, and indeed live very long; by whom also we learn many things.... "We have high towers, the highest about half a mile in height, and some of them likewise set upon high mountains, so that the vantage of the hill with the tower is in the highest of them three miles at least.... "We have great lakes, both salt and fresh, whereof we have use for the fish and fowl.... "We have also a number of artificial wells and fountains, made in imitation of the natural sources and baths, as tincted upon vitriol, sulphur, steel, brass, lead, nitre, and other minerals; and again, we have little wells for infusions of many things, where the waters take the virtue quicker and better than in vessels or basins. And among them we have a water, which we call water of paradise, being by that we do it made very sovereign for health and prolongation of life. "We have also great and spacious houses, where we imitate and demonstrate meteors [weather]--as snow, hail, rain, some artificial rains of bodies and not of water, thunders, lightnings; also generations of bodies in air [spontaneous generation]--as frogs, flies, and divers others. "We have also certain chambers, which we call Chambers of Health, where we qualify the air as we think good and proper for the cure of divers diseases and preservation of health. "We have also fair and large baths, of several mixtures, for the cure of diseases, and the restoring of man's body from arefaction [withering]; and others for the confirming of it in strength of sinews, vital parts, and the very juice and substance of the body. "We have also large and various orchards and gardens, wherein we do not so much respect beauty as variety of ground and soil, proper for divers trees and herbs, and some very spacious, where trees and berries are set, whereof we make divers kinds of drinks, beside the vineyards. In these we practise likewise all conclusions of grafting, and inoculating, as well of wild-trees as fruit-trees, which produceth many effects. And we make by art, in the same orchards and gardens, trees and flowers, to come earlier or later than their seasons, and to come up and bear more speedily than by their natural course they do. We make them also by art greater much than their nature; and their fruit greater and sweeter, and of differing taste, smell, color, and figure, from their nature. And many of them we so order as that they become of medicinal use. "We have also means to make divers plants rise by mixtures of earths without seeds, and likewise to make divers new plants, differing from the vulgar, and to make one tree or plant turn into another. "We have also parks, and enclosures of all sorts, of beasts and birds; which we use not only for view or rareness, but likewise for dissections and trials, that thereby may take light what may be wrought upon the body of man.... We try also all poisons, and other medicines upon them, as well of chirurgery [surgery] as physic [medicine]. By art likewise we make them greater or smaller than their kind is, and contrariwise dwarf them and stay their growth; we make them more fruitful and bearing than their kind is, and contrariwise barren and not generative. Also we make them differ in color, shape, activity, many ways. We find means to make commixtures and copulations of divers kinds, which have produced many new kinds, and them not barren, as the general opinion is. We make a number of kinds of serpents, worms, flies, fishes of putrefaction, whereof some are advanced (in effect) to be perfect creatures, like beasts or birds, and have sexes, and do propagate. Neither do we this by chance, but we know beforehand of what matter and commixture, what kind of those creatures will arise. "We have also particular pools where we make trials upon fishes, as we have said before of beasts and birds. "We have also places for breed and generation of those kinds of worms and flies which are of special use; such as are with you and your silkworms and bees.... "We have dispensatories or shops of medicines; wherein you may easily think, if we have such variety of plants, and living creatures, more than you have in Europe (for we know what you have), the simples, drugs, and ingredients of medicines, must likewise be in so much the greater variety.... "We have also divers mechanical arts, which you have not; and stuffs made by them, as papers, linen, silks, tissues, dainty works of feathers of wonderful lustre, excellent dyes, and many others, and shops likewise as well for such as are not brought into vulgar use among us, as for those that are.... "We have also furnaces of great diversities, and that keep great diversity of heats; fierce and quick, strong and constant, soft and mild, blown, quiet, dry, moist, and the like. But above all we have heats, in imitation of the sun's and heavenly bodies' heats, that pass divers inequalities, and as it were orbs, progresses, and returns whereby we produce admirable effects.... "We have also perspective houses, where we make demonstrations of all lights and radiations and of all colors; and out of things uncolored and transparent we can represent unto you all several colors, not in rainbows, as it is in gems and prisms, but of themselves single.... We procure means of seeing objects afar off, as in the heaven and remote places; and represent things near as afar off, and things afar off as near; making feigned distances. We have also helps for the sight far above spectacles and glasses in use; we have also glasses and means to see small and minute bodies, perfectly and distinctly; as the shapes and colors of small flies and worms, grains, and flaws in gems which cannot otherwise be seen, observations in urine and blood not otherwise to be seen. We make artificial rainbows, halos, and circles about light.... "We have also precious stones, of all kinds, many of them of great beauty and to you unknown, crystals likewise, and glasses of divers kind; and among them some of metals vitrificated, and other materials, besides those of which you make glass. Also a number of fossils and imperfect minerals, which you have not. Likewise loadstones of prodigious virtue, and other rare stones, both natural and artificial. "We have also sound-houses, where we practise and demonstrate all sounds and their generation. We have harmony which you have not, of quarter-sounds and lesser slides of sounds.... We represent and imitate all articulate sounds and letters, and the voices and notes of beasts and birds. We have certain helps which, set to the ear, do further the hearing greatly; we have also divers strange and artificial echoes, reflecting the voice many times, and, as it were, tossing it; and some that give back the voice louder than it came, some shriller and some deeper; yea, some rendering the voice, differing in the letters or articulate sound from that they receive. We have all means to convey sounds in trunks and pipes, in strange lines and distances. "We have also perfume-houses, wherewith we join also practices of taste. We multiply smells which may seem strange: we imitate smells, making all smells to breathe out of other mixtures than those that give them. We make divers imitations of taste likewise, so that they will deceive any man's taste.... "We have also engine-houses, where are prepared engines and instruments for all sorts of motions.... We represent also ordnance and instruments of war and engines of all kinds; and likewise new mixtures and compositions of gunpowder, wild-fires burning in water and unquenchable, also fire-works of all variety, both for pleasure and use. We imitate also flights of birds; we have some degrees of flying in the air. We have ships and boats for going under water and brooking of seas, also swimming-girdles and supporters. We have divers curious clocks and other like motions of return, and some perpetual motions. We imitate also motions of living creatures by images of men, beasts, birds, fishes, and serpents; we have also a great number of other various motions, strange for equality, fineness, and subtilty. "We have also a mathematical-house, where are represented all instruments, as well of geometry as astronomy, exquisitely made. "We have also houses of deceits of the senses, where we represent all manner of feats of juggling, false apparitions, impostures and illusions, and their fallacies.... "These are, my son, the riches of Saloman's House." |

Academy of Projectors in Lagado on the Island of Balnibarbi (1735),

described in Gulliver's Travels

He had been Eight Years upon a Project for extracting Sun-Beams out of Cucumbers, which were to be put into Vials hermetically sealed, and let out to warm the air in raw inclement Summers.... I went into another Chamber, but was ... almost overcome by a horrible Stink.... His employment ... was an Operation to reduce human Excrement to its original Food.... There was a most ingenious Architect who had contrived a new Method for building Houses, by beginning at the Roof, and working downwards to the Foundations.... [Another] Projector ... found a Device of plowing the Ground with Hogs.... In an Acre of Ground you bury at six Inches Distance, and eight deep, a Quantity of Acorns, Dates, Chesnuts ... then you drive six Hundred or more [hogs] into the Field, where in a few Days they will root up the whole Ground.... I went into another Room, where the Walls and Ceiling were all hung around with Cobwebs.... [The projector] proposed ... that by employing Spiders, the Charge of dying Silks would be wholly saved;... ...he showed me a vast Number of Flies most beautifully coloured, wherewith he fed his Spiders; assuring us, that the Webs would take a Tincture from them.... They have made a Catalogue of ten Thousand fixed Stars, whereas the largest of ours do not contain above one third Part of that Number. They have likewise discovered two lesser Stars, or Satellites, which revolve about Mars.... They have observed Ninety-three different Comets, and settled their Periods with great Exactness.... |

|

Instead of fantasizing about utopian societies, why not conduct scientific studies of the many different social structures that have developed around the globe and then use the data collected to create an ideal society? Ferdinand Tönnies (1855-1936) Tonnies was an early contributor to modern social theory. He described two fundamentally different types of social groupings:

Emile Durkheim (1858-1917) Durkheim is considered the founder of sociology as an academic discipline. He saw the fabric of modern society being weakened as cohesive forces like family ties, religious beliefs and cultural traditions fell victim to the stress and disruption of technological development and increased urbanization.

Max Weber (1864-1920) Weber viewed the fruits of modern technological achievements as both producers and products of a new and more rational way of thinking about man's place in the world. Replacing close personal ties with impersonal ones and sentiment-based decision making with a process that is strictly rational might help simplify life in an increasingly complex world, but Weber worried that over-organization could leave individuals feeling trapped by excessive social control and suppression of spontaneity and creativity.

Bertrand Russell (1872-1970) Russell believed that social engineering, central planning, and the impulse to regulate and control complex political and social organizations had asocial and sinister roots. |

|

Ivan Pavlov (1849-1936) John B. Watson (1878-1958)

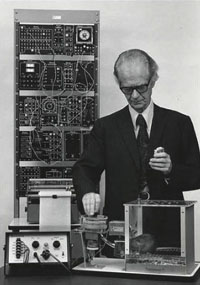

A specialized crib (below) was designed by Skinner to maximize an infant's independence and freedom of movement within a warm and safe environment. It was mistakenly interpreted as a sterile isolation booth akin to the cage-like box (above) Skinner had devised for his experiments on operant conditioning in animals.

|

|

|

| 1914-1918 | Great War (World War I)

use of gas in warfare |

| 1917 | Russian revolution

rise of fascism and intolerance emergency powers entrusted to governments |

| 1920s | dictatorships in Italy, Spain, Portugal, Austria, Yugoslavia, Hungary,

Poland, and Lithuania

worldwide depression |

| 1928 | Stalin inaugurates first 5 year plan |

| 1929 | Stalin issues collectivization decree |

| 1930 | Reichstag elections

National Socialists win first major electoral victory |

| 1931 | Stalin takes control of Party and state apparatus |

| 1933 | Hitler becomes chancellor of Germany |

Herbert George Wells (1886-1946) |

|

The Time Machine (1895)

|

|

Wells believed that human affairs operate best if governed by reason and given direction and purpose by the scientific method. He replaced old style utopias that stressed self-sufficiency, nature, manual labor, small-scale production with those that thrived on the promises of modern technology and scientific innovation. Wells' Views on Real and Ideal Life |

| Current state of humanity | Future utopian ideal | |

| individual | emotional, instinctive | rational, logical |

| family | nuclear or extended families

monogamous marriage natural procreation |

state-controlled families

polygamy eugenics |

| society | individualistic

small social groupings class hierarchy social conflict |

communal

world state classless cooperation social harmony |

| economics | capitalism | socialism |

| politics | nationalism | internationalism |

| ethics | religion-based

ecocentric self-assertion |

science-based

self-renunciation, service, self-discipline |

| intellect | natural sensory experience

debased language |

artificial sensory experience

superior modes of communication |

| nature | vitalistic, dynamic

open country uncontrolled space |

knowable, exploitable

city controlled space |

Aldous Huxley (1894-1963) |

|

Crome Yellow (1921) Antic Hay (1923) Those Barren Leaves (1925) Point Counter Point (1928) Proper Studies (1927) Brave New World (1932) Eyeless in Gaza (1936) The Doors of Perception (1954) Heaven and Hell (1956) |

Huxley worried about the Wellsian vision being taken to extremes. He saw danger inherent in human ambition and the quest for power through science itself. In Brave New World, Huxley views as dystopian the very characteristics

that Wells calls utopian. To scientifically transform society, Huxley

believed that installing new political and economic structures would be

unnecessary. It could be done more quickly and efficiently by altering

individuals' psychology and physiology. In Brave New World,

Huxley darkly envisioned a government run by specialized scientific experts--technocrats.

Individuals' social class, mental capacity and physical structure would

be artificially predetermined by the work for which they were to be responsible.

To maintain the status quo, social behavior and all forms of individual

initiative would be both standardized and effectively controlled by drugs

and intoxicants.

|

A.F. 1

1908 |

Opening date of new era--Introduction of first Model T

Period of liberalism and appearance of first reformers |

A.F. 141

2049 |

Outbreak of "The Nine Years' War" followed by the "Great Economic Collapse." Period of Russian ecological warfare including poisoning of rivers and anthrax bombing of Germany and France. |

A.F. 150

2058 |

Beginning of World Control

Conscription of consumption followed by period of social restiveness and instability Rise of conscientious objection and back to nature movement Reaction to liberal protest movements including Golders Green massacre of Simple Lifers and British Museum Massacre Abandonment of force by World Controllers Period of antihistory movement and social reeducation including intensive propaganda directed against viviparous reproduction and "campaign against the Past" Closing of museums Suppression of all books published before A.F. 150 |

A.F. 178

2086 |

Government drive to discover socially useful narcotic without damaging

side effects

Establishment of special programs in pharmacology and biochemistry |

A.F. 184

2092 |

discovery of soma |

A.F. 474

2381 |

The Cyprus Experiment (establishment of a wholly Alpha community) |

A.F. 478

2386 |

Civil War in Cyprus (19,000 Alphas killed) |

A.F. 482

2390 |

The Ireland Experiment (increased leisure time and four-hour work week) |

A.F. 632

2540 |

The present |

Excerpts from Brave New World |

|

|

Chapter 3

"You all remember," said the Controller, in his strong deep voice, "you all remember, I suppose, that beautiful and inspired saying of Our Ford's: History is bunk. History," he repeated slowly, "is bunk." He waved his hand; and it was as though, with an invisible feather whisk, he had brushed away a little dust, and the dust was Harappa, was Ur of the Chaldees; some spider-webs, and they were Thebes and Babylon and Cnossos and Mycenae. Whisk, Whisk -- and where was Odysseus, where was Job, where were Jupiter and Gotama and Jesus? Whisk -- and those specks of antique dirt called Athens and Rome, Jerusalem and the Middle Kingdom -- all were gone. Whisk -- the place where Italy had been was empty. Whisk, the cathedrals; whisk, whisk, King Lear and the Thoughts of Pascal. Whisk, Passion; whisk, Requiem; whisk, Symphony; whisk.... "That's why you're taught no history," the Controller was saying.... Note: a reporter once asked Henry Ford what he thought of history. He replied, "History is more or less the bunk. We want to live in the present, and the only history that is worth a tinker's dam is the history we make today." Why do you think history is anathema to the World State leaders? Leaders in Brave New World do not bother to rewrite history as those in George Orwell's novel 1984 do. Instead, they simply obliterate it. Chapter 8 One day (John calculated later that it must have been soon after his twelfth birthday) he came home and found a book he had never seen before lying on the floor in the bedroom.... the book was called the Complete Works of William Shakespeare.... "It was lying in one of the chests of the Antelope Kiva. It's supposed to have been there for hundreds of years. I expect it's true, because I looked at it, and it seemed to be full of nonsense. Uncivilized. Still, it'll be good enough for you to practise your reading on." Note: a few citizens in remote regions of the World State still have access to copies of Shakespeare's writing, but they have lost the ability to understand or interpret its meaning. How does this situation compare with that of the Inlanders and the legend of St Eustace in Riddley Walker? Chapter 16 "So you don't much like civilization, Mr. Savage".... "No.... Of course," the Savage went on to admit, "there are some very nice things. All that music in the air, for instance...." "Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments will hum about my ears and sometimes voices." The Savage's face lit up with a sudden pleasure. "Have you read it too? he asked. I thought nobody knew about that book here, in England." "Almost nobody. I'm one of the very few. It's prohibited, you see. But as I make the laws here, I can also break them...." Note: while John is in Mond's study, Mond casually quotes a line from "The Tempest" (see below) which John instantly recognizes. Their discovery that they share an interest in the plays of Shakespeare gives the two men an opportunity to talk and argue about the value of art. When John asks why World Staters are prohibited from reading Shakespeare, Mond first replies simply "Because it's old.... We haven't any use for old things here." Later he adds, "Besides; they couldn't understand it." World Staters could never understand a tragedy like "Othello", one leader explained, not because the language was archaic but because "The world's stable now. People are happy; they get what they want, and they never want what they can't get. They're well off; they're safe; they're never ill; they're not afraid of death; they're blissfully ignorant of passion and old age; they're plagued with no mothers or fathers; they've got no wives, or children, or lovers to feel strongly about; they're so conditioned that they practically can't help behaving as they ought to behave." Does our modern life experience limit our ability to understand the plays of Shakespeare?

|

|