University of California, Irvine

Instructor: Dr. Barbara J. Becker

|

Lecture 15. Constraining the Natural

|

In the eighteenth century, machines began to relieve humans of tedious and oftentimes dangerous labour. Some humans saw only the promise and positive possibilities in this development. Others saw only risk and uncertainty in the rapidly evolving relationship between man and machine. Imaginative tinkerers put their skills to work designing and building new machines able to automate complex processes the textile industry was a good target for mechanization. Much of what needs to be done is time consuming and repetitive. It was a major challenge of the period to design a machine that could produce thread as good as -- and then better than -- a human could spin, or weave cloth that was of satisfactory -- and then exemplary -- quality compared to that which was handwoven. |

|

|

The "putting out" system was viewed as an improvement over the earlier guild system. It was ideal for utilizing low-cost household labor. Surplus journeymen could escape the jurisdiction of guild leaders and set themselves up as small masters. It was especially favorable to the cloth merchants (clothiers) who were protected at each stage against market fluctuations and other unforseen complications by their power to refuse to buy the cloth back, or to buy it back at a low price and then wait for things to turn around. |

| cloth merchant | buys wool | - £ 7 | |

| sells wool to | weaver

sorts, cards, spins, and weaves wool with help of wife and children |

+ £ 8

|

|

| cloth merchant | buys back unfinished cloth | weaver nets £2 |

- £10

|

| sells cloth to | fuller

cleans, bleaches, raises the nap, crops, and stretches cloth |

+ £12

|

|

| cloth merchant | buys back finished cloth | fuller nets £2 |

- £14

|

| sells cloth to | dyer |

+ £16

|

|

| cloth merchant | buys back dyed cloth | dyer nets £2 |

- £18

|

| sells cloth to | agent

takes cloth to trade fair, sells cloth to customer for £40 |

+ £30

|

|

| agent nets £10 | |||

| cloth merchant | nets |

+£17

|

Spinning and Weaving |

|

During the 18th century, machines began to appear that soon changed the way textile work was accomplished.

Kay's "flying shuttle" (1733) The width of the cloth that could be woven on a loom was limited by the length of a weaver's arm because the weft thread -- wound on a spool called a "bobbin" -- had to be passed by hand through the warping. The "flying shuttle" by John Kay (1704-1764?) made this task more efficient. Kay placed the bobbin inside an elongated smooth wooden casing -- called a shuttle -- that was pointed on both ends. The shuttle rode on wheels along a grooved track. By pulling strings attached to the shuttle's ends, the weaver could make it literally "fly" back and forth through the warp threads with ease, no matter how wide the cloth. Before the introduction of the flying shuttle, a weaver required the support of about four spinners (often family members) to maintain a full and steady work load. The flying shuttle sped up the weaving task so much that it could now take as many as sixteen full-time spinners to keep a weaver busy!

For most of human history, the roadblock in textile production has been the spinner. Anyone who has tried their hand at turning raw fiber into thread can attest that it's not easy automating the spinning process. Much of a thread's quality depends on a spinster's dexterity and sensitivity to the delicate interplay of fiber and spindle. But the necessity of employing platoons of hand spinners to keep a weaver supplied with thread motivated the search for a mechanical way to mimic the spinner's art. The spinning jenny (1764) showed it could be done. It was first invented by Thomas Highs (or Heyes; b. 1718)--and improved and perfected by James Hargreaves (1720-1778):

The spinning jenny was driven by human effort. Consequently its output was limited by human strength. And -- unfortunately -- it did not produce thread sufficiently strong to use for warping a loom. In 1767, Thomas Highs developed a plan to use rollers to guide and stretch out the fiber before it was twisted. This important improvement may have been appropriated by the itinerant barber, wigmaker and opportunist, Richard Arkwright (1732-1792), in designing the spinning machine attributed to him -- the "water frame" -- and for which he obtained a patent in 1769. Thread produced by the "water frame" was strong enough to be used as warp or weft. And, because the machine was designed to be driven by a waterwheel, horse, or other non-human power source, it opened up the possibility of building and operating larger and more productive spinning machines.

As soon as thread could be spun by machines in large quantities, the bottleneck in textile production shifted from spinners to the weavers. Edmund Cartwright (1743-1823) was an English clergyman. He had never seen a handloom or a weaver at work, but he had heard of remarkable automatons like the chess-playing Turk created by the French inventor Jacques de Vaucanson (1709-1782). If Vaucanson could successfully reduce so many complex movements into a mechanical routine, then, Cartwright believed, it should be possible to devise a way to automate the production of cloth, a process he conceived as based on a sequence of three simple repetitive actions:

|

(1) shedding (separating and lifting selected warp threads)

Warp threads (red and blue) seen on a simple handloom.

Lifting alternating threads (the red ones) to create a "shed" -- a tunnel-like space between the warp threads.

The "shed" as seen from the side.

|

(2) picking or filling (passing the weft thread through the shed)

The weft thread (shown in green) is often carried on a shuttle. When the shuttle moves through the shed, the weft thread passes over the blue warp threads and under the red warp threads.

Picking or filling the weft thread as seen from the side.

|

(3) beating-up (pressing the weft thread into the "fell" -- the cloth on the loom that has already been woven -- using a "reed" -- a comb-like tool -- to set the weft thread securely in place).

The weft thread in place after the reed has beaten it into the fell. The process can then be started all over again, this time by lifting the blue threads, passing the weft thread through the resulting shed in the opposite direction, and beating it into place. |

|

In 1784, Cartwright devised his first mechanical loom.

His machine was able to produce a piece of cloth, but it proved impractical to use compared to a regular handloom. Instead of employing one weaver, Cartwright's "power loom" required two strong men to operate and it took more time to weave the same amount of cloth. Determined to improve his machine, Cartwright learned how real weavers and handlooms actually worked. In 1785, he patented a new design.

Cartwright continued to make improvements and, in 1787, began using steam power instead of animals to run his looms. He might have made a commercial success out of the sale of his looms, but textile manufacturers became wary of installing the machines after a mill, in which hundreds of Cartwright's looms were being installed, was destroyed by fire in 1790. The fire was probably purposely set by textile workers who saw the power loom as a threat to their livelihood. The owner did not rebuild. In 1793, Cartwright was forced to declare bankruptcy. |

|

|

| Weaving is not the only way to make cloth. Using a pair of hand-held

rods called "needles", knitters can quickly convert a single strand of

yarn into a two-dimensional sheet of interlocked loops. A fast knitter

can work 100 stitches in one minute.

The simplicity of knitting made it amenable to automation at a much earlier date than weaving. The first stocking-frame (1589) is credited to William Lee, a clergyman from Nottingham. With it, knitters were able to work 1000 stitches/minute.

Its was simple enough to use that children as young as 12 years old could be taught to operate it. It is said that Elizabeth I feared the machine would cause massive unemployment. And from time to time, over the next two hundred years, textile workers in many places revolted against the use of this and other machines that threatened to replace the work previously done by human effort. In the early nineteenth century, the stocking-frame became a target of violent action by a disparate group of English textile workers who rallied under the name of a fictitious leader named Ned Ludd. Between 1811 and 1816, the "Luddites" engaged in a variety of riotous acts, many aimed at the destruction of automated machines introduced by clothiers and hosiers in Yorkshire, Lancashire, and Nottinghamshire. The stocking-frame itself was not the real source of discontent for the stockingers who joined the Luddite cause. Stockingers had long used automated knitting machines to make stockings, but they increased or decreased the number of stitches in each row as they went along in order to create an end product that, once removed from the frame and joined with a seam up the back, would conform more perfectly to the shape of a person's leg. Needless to say, this took extra time and required training in order to do well. Hosiers (individuals who were to the stockingers what clothiers were to weavers), eager to increase profits and decrease labor costs, began introducing wide-frame knitting machines on which stockingers could quickly knit a piece of cloth of uniform width. When the cloth was removed, it could then be cut into the necessary shape before being sewn. Stockings made this way (called "cut-ups") were of inferior quality to those made the old way, but they could be made more quickly and they could be made by less experienced stockingers (called "colts"). The stockingers who joined the Luddites wanted to:

|

|

|

It is a fact well known ... that scarcity, to a certain degree, promotes

industry, and that the manufacturer who can subsist on three days work

will be idle and drunken the remainder of the week.... The poor in

the manufacturing counties will never work any more time in general than

is necessary just to live and support their weekly debauches....

We can fairly aver that a reduction of wages in the wollen manufacture

would be a national blessing and advantage, and no real injury to the poor.

By this means we might keep our trade, uphold our rents, and reform the

people into the bargain.

--J. Smith, Memoirs of Wool (1747) |

| Public discourse in America today is rife with raves and rants on the

complex issues raised by terrorism. In England during the 1810s,

it was almost impossible to find a neutral voice on the subject of Luddism.

Depending on who was telling the story, the Luddites were villains or heroes.

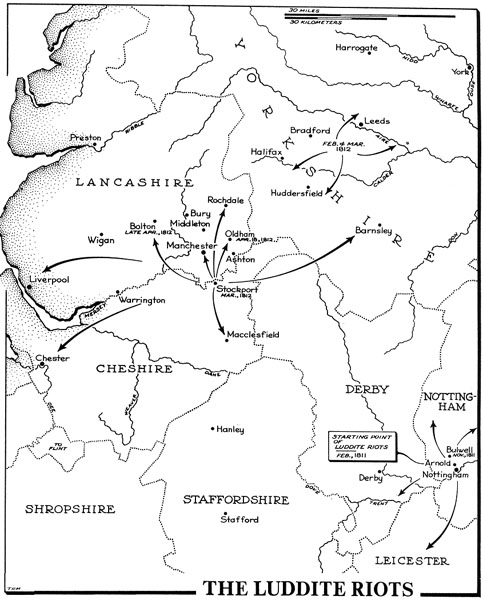

What came to be called the Luddite riots began on the heels of two straight years of bad harvests. The price of wheat had risen by over 50% in London and nearly 90% in northern England. A fully employed stockinger might earn 7 to 14 shillings 6 pence per week; a handloom weaver, 9-12 shillings per week. Daily bread could cost up to 1 shilling 8 pence, or (assuming one purchased bread every day) 11 shillings 8 pence per week! 12 pence = 1 shilling = .05 pounds = roughly 25 cents in 19th century In February 1811 at Arnold--a small town near Nottingham where fabric for "cut-ups" was being knitted on wide stocking frames--stockingers broke into hosiers' workshops and disabled their frames by removing the jack-wires.

The wide-frame stocking machine produced knitted fabric of uniform width from which patterned pieces could be cut to make stockings and other clothing items. After a second riot in Arnold, military troops arrived in early April to quell the disturbance, but by then over 200 frames had been destroyed. In November, in the wake of another disastrous harvest, a new outbreak occurred, this time in the nearby village of Bulwell. It was here that the name Ned Ludd was first heard. Perpetrators acted in small bands, striking particular targets and garnering the support of local stockingers and residents. Those whose financial backing could not be won over by sympathy, were "encouraged" through intimidation: Gentlemen all. Ned Ludd's Compliments and hopes you wil give a trifle towards supporting his Army as he well understands the Art of breaking obnoxious Frames. If you comply with this it will be well, if not I shall call upon you myself.On one night, frames were broken in villages and towns that were 12-15 miles apart, giving the appearance that the movement was well organized. In fact, to some observers, the movement seemed too well organized. Mere stockingers were, in their opinion, incapable of operating at that level of sophistication. The escalating violence at home worried law-abiding citizens of a nation at war and gave rise to a number of conspiracy theories. Perhaps outside agitators were to blame: the Irish? the French? the Americans?--Edward Ludd Local authorities summoned more troops and swore in new constables. In December, a force of 2,000 men was sent. Meetings were held between representatives of hosiers and stockingers to settle their differences. And although no formal agreement was reached, some hosiers found it expedient to abandon cut-ups and to pay higher wages. Nevertheless, cases of frame breaking in the region around Nottingham continued at rate of 200 frames per month through February 1812, when Parliament adopted the Frame-Breaking Bill, which made the destructive action a crime punishable by death. Just as things seemed to be calming down in the Nottingham area, new disturbances erupted in Lancashire, Cheshire, and Yorkshire. The Yorkshire moors were the center of the cropping, or shearing, branch of the woolen industry.

Croppers worked in small collectives to finish newly woven cloth by raising its nap and then shearing it -- time-consuming jobs that had always been done by hand. In fact, croppers reacted positively when clothiers began purchasing labor-saving devices -- first the gig-mill for nap raising...

The gig-mill automated the tedious process of raising the nap on a fabric. and then the automated shearing machine.

The shearing machine automated the process of cropping the fabric. But in troubled economic times, as work became scarce, croppers resorted to machine breaking to protect their livelihood. The area around Huddersfield,

a town about 15 miles southwest of Leeds, witnessed the eruption of Luddite-related

violence:

|

| 22 February 1812 | Two cropping shops (in Marsh and Crosland Moor) attacked by masked Luddites armed with firearms, hatchets and hammers |

| 5-6 March | Two cropping shops attacked in Linthwaite |

| 13 March | Small, well-organized nighttime raids carried out in South Crosland, Honley, and Lockwood |

| 15 March | Bigger, more violent attack at Taylor Hill; more damage: windows smashed, shots fired indiscriminately, attempts to start a fire; owner was member of the newly-formed committee against the Luddites |

| 5 April | Three workshops in Holme Valley attacked |

| 9 April | Destructive assault on mill at Horbury involving 300 men and causing almost £300 damage |

| 11 April | Major attack on mill in Spen Valley defended by militia; two Luddites killed |

| 18 April | Mill owner, William Cartwright, shot at in Bradley Wood |

| 28 April | Mill owner, William Horsfall, shot and fatally wounded at Crosland Moor |

| 29 April | Arms seized from clothier's home |

| 22 July | Suspected informer--clothier, John Hinchcliffe, of Upperthong--was shot and badly wounded; local criminals suspected of pretending to be Luddites while committing burglaries |

| 2 January 1813 | Three young Huddersfield men--George Mellor, William Thorpe and Thomas Smith--charged with the murder of William Horsfall; all found guilty |

| 8 January | Mellor, Thorpe and Smith hanged

|

| 9 January | Eight men charged with attack on William Cartwright's mill; three acquitted |

| 16 January | Five men, found guilty, hanged |

| March 1813 | Nine more suspected Luddites hanged for stealing arms or money |

| By May, the region had quieted down, and most of the soldiers were withdrawn.

There were minor outbursts of machine breaking in the summer and fall of 1814 and 1816, but more and more often, the damage done was found to be the work of mercenary gangs, not cadres of oppressed workers. Between 1806 and 1817, the number of gig-mills in Yorkshire increased from 5 to 72. Eventually, the craft of nap raising disappeared. Stockingers realized the futility of insisting on the abolition of cut-ups. Realizing that goal would have severely damaged the textile industry at its one growing point and contributed nothing towards raising wages. |

|