|

Composing a Life:

by Barbara J. Becker

If you have known how to compose your life, you have accomplished a great deal more than the man who knows how to compose a book.—Michel de Montaigne

The unexamined life is not worth living.—Socrates |

|

Composing a Life:

by Barbara J. Becker

If you have known how to compose your life, you have accomplished a great deal more than the man who knows how to compose a book.—Michel de Montaigne

The unexamined life is not worth living.—Socrates |

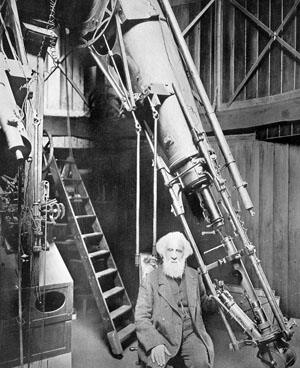

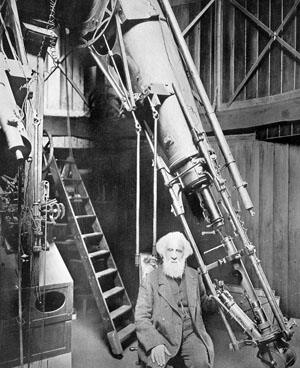

In Telling Lives in Science: Essays on Scientific Biography, Richard Yeo and Michael Shortland suggest that "biography springs from unconscious motivations." Perhaps. My own interest in composing a life of English amateur astronomer William Huggins (1824-1910) was born out of a conscious desire to understand the structure and function of the boundaries of acceptable research that surround a given segment of the scientific community—how are they established, policed, altered.

My curiosity about the general issue was piqued during a graduate seminar on conceptual transfer. Hybrid disciplines, in particular their evolution and development, served us as exemplars, or perhaps you might think of them as specimens in an historian's laboratory, from whose dissection we would derive insight into the social and political dynamics of specialized scientific groups.

I chose to examine the development of astrophysics, a hybrid discipline whose emergence and efflorescence required the wholesale restructuring of the boundaries surrounding the theory and practice of astronomy. Knowledge of the physical and chemical structure of celestial bodies was deemed unattainable by proper scientific methods, and hence relegated to the no-man's-land of mere speculation. One might entertain any number of untestable ideas about the origins of the stars, and the reasons for the differences in their colors, brightness, and distribution, but such was not the stuff of science.

What was deemed positively knowable was the location of a celestial body on the sky. The gathering and interpretation of this information defined the mission of the practicing astronomer and determined the structure of his creative thought and workspace:

What are the tacit rules that one must follow in investigating the natural world. What questions are appropriate to ask. What would good answers to such questions look like and how would they be recognized? What would constitute an acceptable way of finding those answers? Who can be allowed to participate in the search?

Astrophysics as we know it today is built on a range of questions and methods that were unimaginable to individuals in the first half of the nineteenth century. I wanted to know more about what made it possible to include such an unorthodox line of investigation within the traditional astronomical community. What prompted a segment of practicing astronomers to move into this new thought space? If science is (to its credit) an inertial system, how do changes like this come about?

I saw Huggins as a convenient foil to tell the story of the origins of astrophysics. After all, he had published a concise yet intimate account of his life's work. He worked his way in from the periphery to an inner circle of late nineteenth century astronomy. He authored numerous articles which documented his investigations. Plus, his wife Margaret, had bequeathed a set of six observatory notebooks to Wellesley College which, from published descriptions of them, promised to put human flesh on the skeletal scientific prose of the public accounts. It was all very straightforward. Perhaps a little too straightforward. As Robert Reich wisely observed concerning disparities between his own and others' accounts of things he said and did while Secretary of Labor—"My account matches my memory, even if it doesn't match events." The same could be said for William Huggins. The straightforward story is always a lot more complex—and a lot more interesting.

Lives are mosaics fashioned out of numerous incremental day to day decisions and happenstance, what historian Pamela Smith has referred to as the "noise" of a life. Often, in public accounts, these incremental events, are selected and arranged by the individuals themselves, their contemporaries, and those who follow, to fit a coherent pattern. Individuals like Huggins, who operate on the periphery are, to me, an interesting class of actors within the scientific enterprise. Their efforts to gain a foothold in one or more esoteric circles within the community at large make visible otherwise tacit or at least subtle acts of negotiation and maneuvering. When such an individual succeeds despite the fact that the proper channels were not accessible, the historian may find, in private accounts, the tell-tale signs of the tunnel that was dug to breach the walls.

Private accounts reveal the rough edges of decision making. They even reveal that some decisions never really get made with conscious finality even though an individual may later recall the matter having been resolved long ago. Why bother with such cumbersome and potentially distracting episodes in an individual's life?

Like scientists, historians strive for simplicity—covering theories which explain much about a wide-ranging collection of things. The clutter and confusion, deadends, and mistakes of a life are presented as aberrations, or at the very least, unique, possibly amusing incidents separable from the whole.

Yeo and Shortland relate Albert Camus's observation that others lives seem so unified and organized while our own seems so incoherent. It might be said that the illusion of unity in the lives of others is what links biographer and audience. The desire to vicariously experience that sense of unity missing in our own lives is a part of what draws us to write and read about it in another's life. There is, then, as Yeo and Shortland point out, a symbiosis between the biographer and the audience: The audience wants to learn and the biographer wants to instruct others.

We may write biography for selfish reasons—because it gives us great personal satisfaction—because it's there—to learn something about ourselves—to get published. But getting published furnishes reading material which hopefully generates an audience, an audience that presumably selects this particular material because they find something instructive in it, something which holds, as t'were, a mirror up to their lives.

Biographies grow out of our collective desire to provide and gain guidance and support from examples in the past—to aid us and our contemporaries in confronting the challenges we see facing us today. How did people like us cope with such challenges? How did they deal with life? What informed the decisions that person made? How can we avoid the same mistakes they may have made? What can be learned from an examined life—even if that life is not one's own? What is it we feel a need to learn?

Our generation is beset by worry and stress, uncertainty and professional angst:

Work in collaborative teams can paradoxically burden the individual researcher with a disorienting and disillusioning sense of isolation.

Professional anxiety stems from basic science's dependency on government patronage in a time of increasing limits in resources and decreasing public empathy.

Tensions between public and private work and thought space raise serious questions of ownership and autonomy in today's laboratory.

The interface between instrument and human operator is the locus of an increasingly rich dynamic—even small adjustments can lead to changes in research design, commensurate adjustments in information gathering, recording, interpretation, and standardization.

The organization of science, the distancing of science and scientists from the popular affective domain, the growing abstraction and complexity of basic scientific knowledge...

The list goes on and on, but the common threads are the production, exchange, and consumption of knowledge.

What biographers and the audience for science biography seek are role models whose lives provide guidance for the conduct of their own lives, or maybe just a comrade with whom they can commiserate. The language and themes of contemporary science biography betray an accommodation to this thrust. There is, for example, renewed appreciation for, and interest in, the lives and work of early modern natural philosophers and mathematicians as trail-blazing science salesmen. We find vivid metaphors of exchange in science biography. Words like "discourse," "moral economy," "patronage," "currency," for example, are all in common use. Issues involving the use and abuse of resources are discussed in terms of access, development, exchange, destruction, negotiation, hoarding, limitations....

What are the commodities being exchanged? Ideas, words, instruments, techniques, opinions, influence, prestige, control, money.... The means of exchange include haggling, barter, reward, appropriation, theft, entitlement, and purchase.

Science biographers and their audience have become tolerant of a wider range of scientific personalities. Personal ambition, for example, is presented as less of a negative, perhaps mercenary quality, and more as one trait among many with which a scientist may be armed for survival in the professional struggle for existence. Unbridled curiosity and desire to contribute to the general welfare may be viewed as more noble personality traits, but they are increasingly being recognized as characteristics of the euphemistic public face of science. Archival work and attention to an individual's daily practice helps the historian unmask that face.

Fictionalized biographies of real people: Jean Hamburger's diary of William Harvey, for example, or John Banville's works on Copernicus and Kepler; and even biographies of fictional people: Daniel Defoe's tale of one man's experience with the plague outbreak in London, Mary Shelley's tale of the ethical struggles of Dr. Frankenstein—all provide guidance in the same way that strictly archival biographies do. Sometimes even better.

Michael Segre's impressionistic portrait of Galileo as seen through the work of his disciples focuses on the impact of the individual and permits us all a view of the individual through the eyes of those who knew him in life. In a similar way, David Hull's Darwin and his Critics gives us Darwin in relief—what contemporaries found lacking in him and his ideas.

Sifting through the archival shards of another's life, we accumulate an odd collection of details, and not, I might add, necessarily in the most convenient order. Aided by an abstract form of haptic processing, we manipulate these details in our minds until a vivid three-dimensional image emerges—we see the face, the instrument, the laboratory; we hear the voice, the scraping of the observatory dome, the zapping of the Geissler tube; we feel the frustration, the joy, the fear; we smell the battery's noxious fumes, the burning magnesium, the sweet night air; we taste the sweat, the ink, the long-forgotten cup of tea.

As our subject comes alive and stares us in the face, our task, indeed our challenge, as biographers is to capture and preserve this mind-image—make it possible for others to sense it, to know it, as we do. We cannot, like Kepler, reconstruct our research steps pace by pace, piece by piece. The audience—those we hope to acquaint with this image—do not have the same endurance, the same driving curiosity to know all there is to write about. We must pick and choose. We must be economical in our use of words and instances, and yet generous enough so that we do not leave egregious gaps. We must veil, or at least encapsulate, our tedious detail-laden research so it does not distract or repel the reader, while providing enough support for our statements and conclusions and speculations to build the reader's confidence in what we wish to tell them, to make science come alive for them, and in so doing to let them know that scientists are complex people with annoying personalities and offensive social skills, with charm and pluck and wit, with uncertainties and fears.

![]()