|

Midterm ExamPage Midterm: Monday, Feb. 10 |

|---|---|

Form of the midterm exam •The exam is divided into 2 parts. • You should spend half of your time on each part. • Be as specific as you can.

• Use a bluebook. •Do not use books, computers, phones, notes, or any other study aids during the exam.

|

Part I. Choose 5 of the following 6 terms and explain the significance of each; in the course of your response, you should refer to a work or works read for the course. Example: Heroic couplets

Part II. There will be two quotations. Choose one and follow the directions below. (a) Identify the source of the quotation. (b) Then paraphrase it. (c) Then analyze it. Use your analysis to make a claim about the quotation. Example: For his long absence Church and State did groan;

|

Examples of strong answers for Part I: 1. Desire is the driving force for all human actions. Hobbes’s Leviathan argues that humans have a never-ceasing desire, which is why no matter how much they accumulate, they will always be warring for more. Wycherley’s The Country Wife follows this notion in exemplifying Horner’s constant cuckoldings and even the Virtuous Gang’s façade that they are ladies of honor. In Hobbes’s and Wycherley’s works, it is argued that in order for a society to function, this constant desire must be controlled. In Leviathan, it is done by social contract . . . In Wycherley’s work, it is shown that desire does not have to be entirely eliminated, but it must not be displayed when in a public setting. It is also necessary to lie to one another about desire to prevent society from falling apart. 2. Marriage ending is a term closely linked to The Country Wife. As marriage is a key institution to maintain societal standards, the playwright satirizes how it is seemingly a joke. Marriage maintains order in society because it promotes inheritance, which is very important because inheritance carries on power and wealth. To have a marriage end is like going against the social customs, and causing a great disorder. The character Lucy especially reiterates that fact when she implores Margery Pinchwife to lie to her husband and stay married to him even though he makes her want to vomit. 3. The Marriage ending is typical of comedic plays. It usually involves the entire cast in attendance and signifies the happy resolution of the plot. The Country Wife, however, is a satire; therefore the marriage ending is not merely a conclusion , but a social commentary on and criticism of marriage. All of the married couples in the play have been involved in some kind of deception (Harcout schemed to steal Alithea from his friend Sparkish; Margery loves Horner but has to protect her marriage; Mrs. Fidget and the other ladies have had their own affairs with Horner). Pinchwife and Margery seem particularly unhappy (for Pinchwife knows he has been cuckolded and is being lied to, and Margery’s eyes are now open to the joys of desire), and there is even an indication of violence in their relationship. A lot of the characters are restrained or unhappy by marriage, and yet they insist on the social institution of it. The Country Wife therefore satirizes the typical marriage ending, for it is not a happy resolution at all.

Examples of strong essays for Part II: 1. This quotation is from John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester’s Satyr Against Reason and Mankind. This stanza is approximately lines 48-71 and paraphrased is as follows: [What anger] rots your (Rochester’s) foolish mind that you rant against the elevation of reason and man over animals? Man is blessed. Man alone, not animals, was given a soul by Heaven and made by God in His image, and He dressed us in the ability to reason in order to make man superior to animals. Reason, which has influenced you (R) to write this poem, argues against the senses especially in perceiving the physical world. Reason allows man to explore unanswerable questions and go beyond the limits of the world to search the realms of G-d in order to answer these questions which give both Hope and Fear. The “Satiric Adversary” [gives] a counter-argument with the purpose of emphasizing the main argument. In this section, Rochester argues against himself. He chastises himself for “rail[ing] at Reason, and Mankind.” Rochester would have surely had readers in support of Reason over the senses. The satiric adversary would be their argument against the senses claiming that it is because of reason that we are superior to animals and seek out answers to mysterious questions. It is this search that Rochester seeks to criticize. It is an “ignis fatuus,” a false light. Proponents of Reason spend their entire lives chasing unanswerable questions only to learn they wasted their lives. What they should be doing is perceiving the world through the senses, not Reason, and must acknowledge equality to animals, not their sinferiority. 2. The source of this quotation is A Satyr against Reason and Mankind by the Earl of Rochester. In these lines, the “satiric adversary” makes a claim for mankind’s true superiority to all other creatures, because God gave man alone a soul and a capacity for reason, in his own image. The satiric adversary (a clergyman in this poem) says that with his God-given reason man can “take a flight beyond material sense” and can explore life’s mysteries, through which he has access to truth, “Hope” and “Fear.” 3. Quotation: John Wilmot, Earl of Rochester, Satyr Against Reason and Mankind. |

|

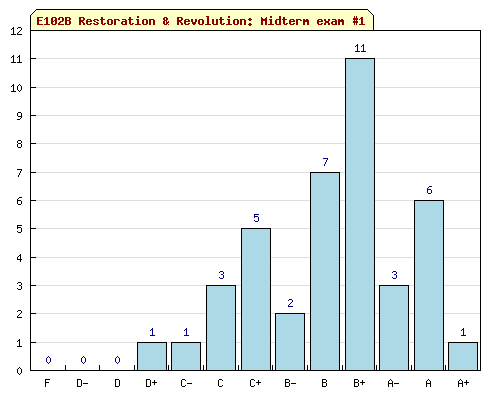

Midterm grad graph Two grades not yet included |

Standard Graph

|